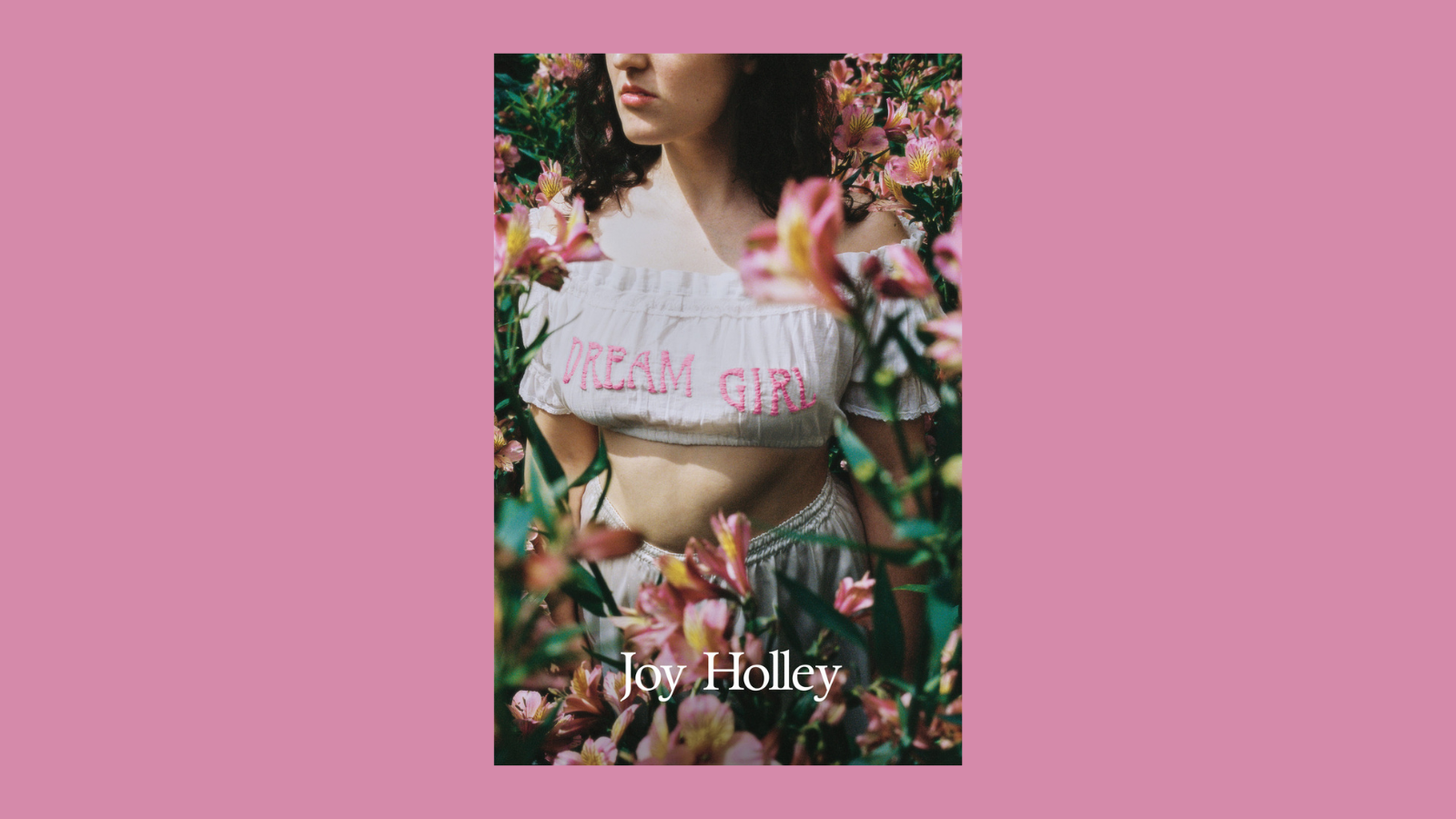

Joy Holley’s debut short story collection, Dream Girl, is a gossamer portrait of high femme adolescence set in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. With her vibey vignettes of the Wellington social scene, gothic retellings of local history focalised through starry-eyed young women, and tales of yearning, Holley has the wants of her target demographics (girls and gays) down pat. Dream Girl is, I believe, a progeny of the contemporary coquette’s darlings—Picnic At Hanging Rock, Lana Del Rey, Brandy Melville, The Love Witch, Esther Greenwood and her Avon makeup kit—and Holley’s imagery and thematic concerns will be familiar to anyone who encountered 2010s Tumblr idolatry of feminine languishing. Fruit, flowers, lipstick, lace, desire, becoming—it’s all there.

In keeping with Holley’s Virgo sun, the women populating Dream Girl are not spontaneous, but careful, even neurotic, about the staging and execution of their desires. Holley rarely begins in media res, preferring instead to show the conception of a plot before its realisation. For example, ‘Mission Strawberry’, the collection’s opening story about a planned seduction in a strawberry field, begins “Mission Strawberry was my idea.” ‘The Heart-Shaped Bed’, in which a woman exerts enormous effort to arrange a room around a cumbersome bed, starts “Alice had wanted a heart-shaped bed since she was sixteen.” ‘Rat Trap’, a woman’s scheme to lure her crush to her house, opens, “I had entertained the idea of calling Lena about a fake rat for a long time before I actually did it.” By grounding anticipation into the realm of arrangement and organisation, Dream Girl channels yearning into neurosis and fantasy into stagecraft. This is apparent in how Holley often depicts her characters consciously constructing their own image, like in these lines from different stories:

“I got out my makeup bag and started brushing out my eyebrows. I never wore much make-up, but I always made sure I looked perfect before seeing Wallace. They didn’t know anything about make-up, and I suspected they didn’t realise I was wearing it a lot of the time.” (‘Mission Strawberry’)

“I had put on perfume earlier too, so it wouldn’t smell too fresh by the time she arrived. I’d picked a cotton dress that looked casual enough to be something I would wear around the house, but also sexy. I’d curled my eyelashes and applied the lightest lick of mascara.” (‘Rat Trap’)

These rituals, aimed in each instance at accentuating the subject’s constructed image while obscuring its artifice, comprise some of the most charmed pleasures of this text and its fantasies.

One of the functions of Dream Girl’s luxurious neuroticism is to create and sustain a utopian vision of idealised girlhood, drawing out the obsessive processes of feminine desire while staving off the drudgeries of reality. Given the book’s interest in the mediated image, it’s fitting that this vision partially derives from a frequently-alluded-to filmic lineage. ‘Blood Magic’, a story about a sexy vampire, directly channels the influence of Jennifer’s Body through a projector, while the Virgin Mary statuettes in ‘Material Girl’ feel like a loving nod to Virgin Suicides. As one of many gestures to the book’s own queerness, a poster of Portrait of a Lady On Fire is plastered on the titular material girl’s wall. A dream girl, according to Holley’s collection, is one who seeks to reside in these images. All those conventionally attractive starlets, the pink and red hearts, the angel-food cake, sweet fruit, long-haired beauties in their first communion whites sequestered together in pretty bedrooms, combined with the feminist, gothic counterparts of man-eaters, witches, and haunted women stowed away in the attic. In this fantasy, women are cut off, therefore freed, from the soul-crushing grind of being a tax-paying, labouring adult.

“Holley’s imagery and thematic concerns will be familiar to anyone who encountered 2010s Tumblr idolatry of feminine languishing.”

Like most utopian visions, this version of girlhood is necessarily exclusionary, and it’s interesting to examine what the characters of Dream Girl wish to exile from their haloed kingdom. When Alice, the protagonist of ‘Heart-Shaped Bed’ is cleaning the bedroom she shares with her boyfriend, Eric, to accommodate the new bed she has purchased, she notices the incongruity of certain items.

“She hooked the curtains back onto the rail. They seemed uglier than before. Eric’s desk seemed uglier too. The heart-shaped bed made his technology look out of place. Surely he didn’t need all of it in here. She unplugged a few unnecessary-looking things and moved them out into the hallway. She pushed the rest far under the desk, hidden from sight.”

A preoccupation with ugliness attaches itself here primarily to objects associated with the male figure in the text—Eric. Consider the following sentences from ‘Cottagewhores’, a short prose work describing the tenancy of “three beautiful women” in a yellow cottage:

“We stay up past the witching hour and into the crackhead hours. After we’ve had a nap, we order Uber Eats. The delivery guy knocks so hard the house shakes.”

Just as in ‘Heart-Shaped Bed’, the presence of masculinity undermines, literally shakes, the characters’ sanctum. When men appear again in the text, they do so alongside the waning glow of the Cottagewhore fantasy: “One flatmate gets her hours cut. One gets such bad leg cramps she can’t walk. Two break-up with their boyfriends.” Another thing shared by these examples is the antagonistic framing of waged work and its tools—the technology required by Eric who “does something with computers” for a living, the Uber Eats delivery guy doing his job, and the flatmate losing her hours all signal a rupture in the fantasy. However, the book is not straightforwardly anti men or anti-work. Cooking and cleaning are allowed, even treated as an indulgence. The text also submits a few permissible kinds of men, like the “Lolita-loving, Sugar Daddy type”, or boys like James Dean and a young Leonardo DiCaprio. Housework and men such as these fit neatly into a traditional feminine fantasy that idealises the domestic and rejects the industrial. Those who dream of a perfect girlhood dream about making meals for their loved ones, not toiling in front of a computer for Datacom or manufacturing iPhones in a sweatshop. It’s DiCaprio as Romeo who’s desirable, not Ernest Burkhart. Humbert Humbert is famously unemployed (he’s a ‘literary scholar’).

For all the lushness of its subject matter, Dream Girl is written in surprisingly spare prose. Lolita may be referenced in the book, but Nabokov’s influence is absent from Holley’s measured voice. Instead, her writing is characterised by short sentences, tempered descriptions, and generous use of parallel syntax:

“You had friends who’d hooked up with her. They all said it was good, really good, but they were always drunk, or on drugs, and couldn’t remember exactly how it went. They remember her knee pushed between their legs. They remembered her mouth in the dark. They remembered telling her they hadn’t done this much before, and the way she said, That’s fine.”

What is the function of such a controlled style? The ordinary, even conversational, nature of Holley’s writing style serves to suppress the dreams her characters attempt to divulge. These characters can never quite seduce the reader into joining their illusions. While their words can successfully provide the material facts of their content (“her knee pushed between their legs […] her mouth in the dark”) they struggle, or refuse, to convey the full intensity of their experiences (“it was good, really good”). The result is a work that feels self-aware, savvy to the naivety and romanticism of its subjects who, for all their beauty, lack the guile or motivation to draw us into their worlds. In ‘Mission Strawberry’ the narrator tells us their crush had a dream, but withholds the specifics of it from us:

“Like brutish men and industrialisation, we, the critical readers, are denied entry to the Haus of Hot Girl.”

“We went strawberry picking in my dream last night. […] They began describing the dream in extreme detail. […] Wallace finished describing the dream just as the song ended.”

Like brutish men and industrialisation, we, the critical readers, are denied entry to the Haus of Hot Girl. If they aren’t careful, the characters are also at risk of being evicted. To survive, desire must be suspended, protected from its own realisation and therefore, in text form, from its communication. The narrator in this scene from ‘Blood Magic’ becomes an intruder to her own desires:

“There was a drug-like happiness, similar to the feeling I had when I woke up from a dream about Ada, but there was also a sickness, a slipping away, a sealing off. I could feel myself falling from one dream state into another. In my mind, someone was opening the door.”

It’s as though, in trying to tell us the “drug-like” truth of her fulfilled desire, she has become alienated from it. Perhaps the simplicity of Holley’s prose seeks to preserve the fullness of women’s and girls’ experiences, a kind of literary iykyk.

Featured cover image by Lily West via Te Herenga Waka University Press.