I do a body scan before the show. No tingling or jitteriness, the classic signs of nerves. My palms are dry, hands are unclenched. I am calm. I think so.

I come to the show with my dad, because I wanted to take him. Maybe he could bring light to some of the aspects of the work I didn’t think I could understand. I think of my dad as an encyclopaedic well of the mainland, and not without reason—we once walked the length of Nanjing Road with him as impromptu tour guide, pointing out historic buildings while my mum shrugged and said, oh yeah, I guess so.

But I felt shy asking him to come—like all father-daughter relationships, we are open with each other only to a degree. A few nights ago, I threw the pitch about the show to my parents, hoping my mum wouldn’t say yes. I felt bad for excluding my mum. She is more . . . not to say she is not academic (she has expressed an interest in dance before), but she watches Marvel movies. Her current hobby is hours of scrolling on Douyin.

So I feel bad, but I get what I want. She doesn’t want to go anyway because theatres make her fall asleep. It’s the dark of the space and having to sit still, she says.

Here me and my dad are, in the dark of the space, making conversation in the chopped/screwed Shanghainese-English only we understand. The lights go down.

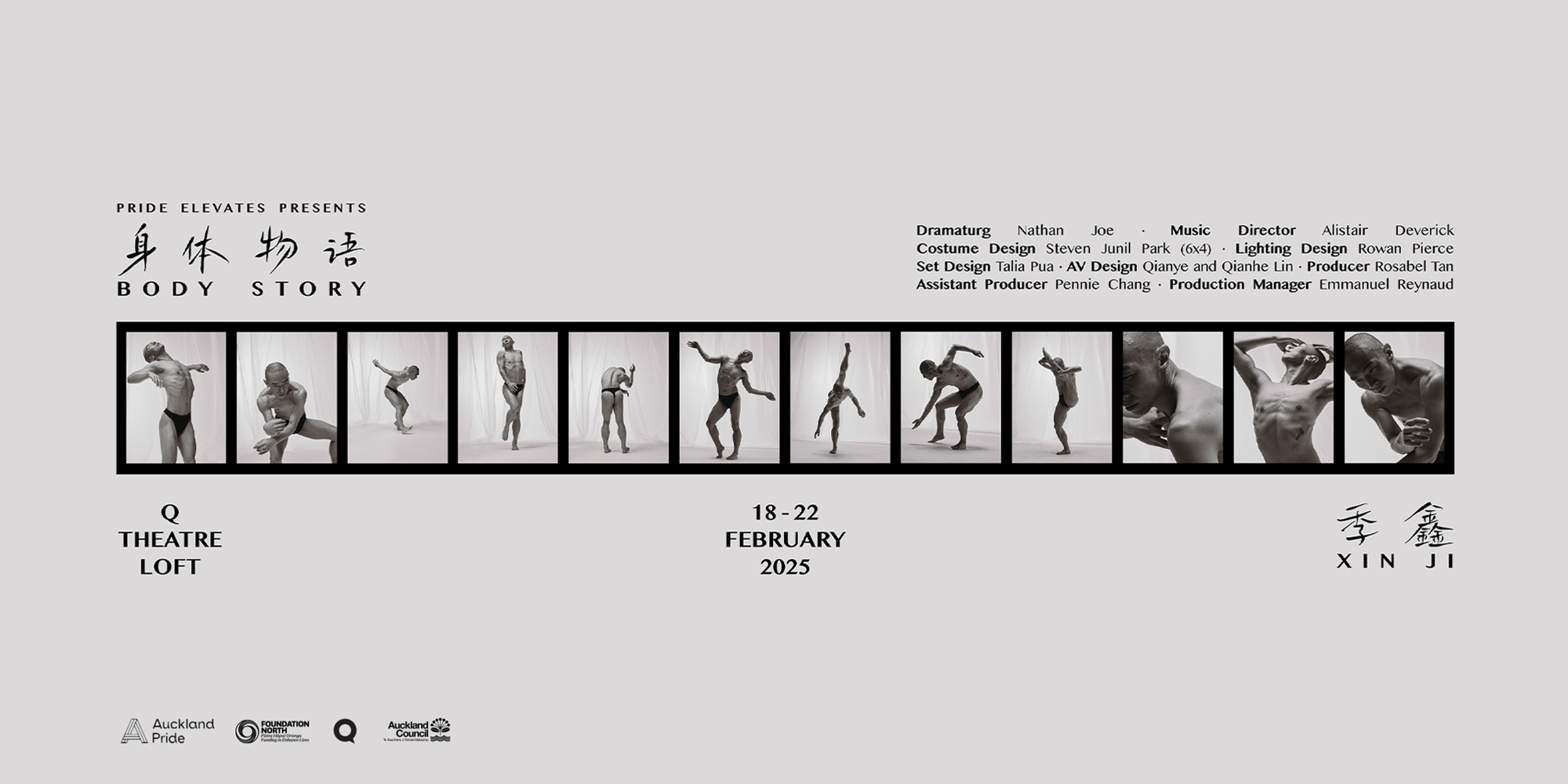

Body scan: I am . . . excited! A scan of the people involved in bringing the work to the stage brings familiarity and high hopes. It’s truly a kaleidoscopic amalgam of the Asian arts scene, a who’s who and if-you-know-you-know’s.

The lights come up. A body—the eponymous body, Xin Ji—comes to the stage. Then a second body I don’t expect, relegated to a musical-instrument space demarcated by organza sheets that dress the rest of the stage. I deduce it’s Alistair Deverick and think, fuck I love a live music piece.

A brief silence and then, movement. Xin’s dressed in silver, like a little bell. Like thick insulation wadding. There was something like that under my childhood home that you could see when you went into the carport. On Friday nights, my dad and I would hang the week’s washing under the carport, a single dusty bulb illuminating the crinkles and folds of the insulation wadding.

Over the music, there is a spoken word element with a structure I can only describe as (no shade) Nathan Joe-core. In his dramaturgical role, I wasn’t sure what hand he would play in shaping the work, especially with a practice famed for expression of movement without speaking. Now here it is, in a word association type of text. Body body body . . . I don’t recognise the voice. I don’t think I’ve ever heard Xin speak. Xin’s head rattles around, arms still—only when he moves them do I realise they’re really his arms. Like a paper doll.

A run of LEDs flash white, running back and forth along the row, Xin backlit that turns the body into spindly silhouette, form vaguely resembling body. There’s no doubt what a controlled and practiced dancer at the peak of his career Xin is—there is something deeply mesmerising in his movement that warrants a solo show that displays these talents.

Projections of a past Xin become a dance partner, echoing through layers of organza sheets at different depths of the stage. In places, Past Xin replicates Present Xin’s stature, and in other places Past Xin becomes larger than life. At times, Present Xin becomes trapped in the outlines of Past Xin, smaller, breathing movements synchronised. What does it mean to dance with echoes of a past self? When do you realise you’re just dancing alone?

A new outfit is adorned: organza and shadow slices the body into sections, echoing the layered organza sheets of the set design. Another moment of expert costuming by Steven Junil Park accentuates the movement while the body is laid bare, it’s part of a curated sparseness in visuals outside of bodies on the floor —set by Talia Pua, AV and lighting design by siblings Qianye and Qianhe ‘Al’ Lin—all working to interact with one another to ultimately centre Xin as the Body.

And then, Alistair pulls the curtain back and comes out of his music-making subsection of the stage. Can he do that? He becomes the second real body in space. What does it add to the reading of the play that the only other body is a white body? A second body that begins to pull, push, stretch Xin into wince-worthy pain. What pain is necessary, how does a body pushed and prodded begin to push back, begin to tire?

Across the work, I return often to The Body Keeps the Score, a book I’m only familiar with in meme format. I later read that two (of three) methods to treat trauma is “(re-) connecting with others, and allowing ourselves to know and understand what is going on with us, while processing the memories of the trauma” and “allowing the body to have experiences that deeply and viscerally contradict the helplessness, rage, or collapse that result from trauma.”

No doubt is Body Story a work that ultimately centres joy. Trauma is repurposed, transformed from leg pulled taut, bent backwards into queer joy, muscle memory channeled into something new. Muscles transforming with new capabilities. A joyful action: legs splay open with a thud, “I realise I am gay” elicits a chuckle from the audience. But still, the stories told give me an indescribable feeling of sadness—what a cliche to associate Asian culture, Chinese culture, as a culture that does not ask for openness and truth. Only giving a version of truth that saves your family and community from each other. Saving face. Insulation wadding.

Body scan. I feel . . . what am I thinking? I think Body Story is a play about truth. Openness, nakedness, rawness, stretching, flexing, confession of desire, pain, pushed body to the limit. Does this require something truthful in response? I think about myself. I think about having to open up. I think I hate that. I think how classically Chinese, not wanting to be emotionally open.

I think about what it means to be Chinese, broadly speaking. Contextually so different from Xin: when I was eleven I was not training at an elite dance school. I was just being a child, here. I liked art and playing with my siblings and was elected class councillor ‘cause I was smart. I fulfilled Chinese stereotypes well enough to want to act in opposition to them. I think about separating that child, both children, from their families at eleven. I look at my dad in the present. I don’t think I could do that. Be separate. I think, ‘How long does it take to untie oneself from familial expectation?’ Not by my age, not by Xin’s age.

Am I still insecure about being Chinese? Not really at all, but also all the time. Yes, with the relatives I have only met a handful of times in my life and feel the pools of silence in our strained conversations. Yes, where my garbled Shanghainese becomes so unintelligible to even my dad that it’s better for the both of us if I just switched to English. Hugely when me and my mother are out, and I am spoken to in Mandarin and I stare at my mum willing a translation she forgets to give. Maybe I’m only Chinese in the context of Aotearoa, defined by the visual marker that others. In China, I would/could not be a fully truthful self, but;

Am I a truthful self here in Aotearoa, or is there always a level of mediation that demarcates the honest self? Does the sum of parts make a whole?

Am I my true self in my work-sona, with an accent so Middle New Zealand, so clearly enunciated, that it could only return the most profit per customer? My personality whittled down to the bare bones of grateful immigrant, always in service of others.

Am I my true self when I’m around non-Chinese people, the constant mediation of behaviour plaguing every action in fear of potential, possible danger? I hold my tongue, I always gauge someone’s likelihood for a casual racist or homophobic comment. I always check the exits.

Am I my true self talking to other people theoretically just like me: second generation Chinese, queer, gender(?), because even in that instance can I expose myself? Are we really the same until we eventually find we are not? Are we comrades, or will we tear each other limb from limb in order to climb the hierarchical ladder of ideological identity markers? Can I open my mouth, can I say I trust you? Do we trust each other?

And then I am in the dark of the theatre again, listening to Xin’s heartbeat racing to steady itself. He lies there with a stethoscope hooked up on a line and placed atop the deep inhale and exhale of the ribcage. Alistair feeds the line into the shadow of the stage—the space between beats slowly refills with a more full-bodied sound, bringing a oneness to the sound design and the dance, beginning again in full ferocity. The show operates as a striptease, where a more and more naked self exposes a true self. Sweat flicks off the brow in an impressive spin and leap into the air, “the body the body the body . . .” There is a new freedom, or lack of self-consciousness in the movement in this final act, as if to tell the truth, to be honest to others is to be uninhibited. On the moment of applause Xin gives one more victory lap, a tiny, final encore, smiling the whole way through.

The sun is still up as we walk to the car. My dad says Chinese ballet looks for a specific body type. “Tall.”

“Skinny?” I offer.

“No,” he says, “Long limbs.” Things that seem somewhat out of one’s control.

“Maybe he didn’t want to do ballet anymore.”

A pause, then my dad says:

“I wonder if the stories are true.”

I’ve avoided coming out to my parents, even though it would be fine. Would it be fine? I mean, the secret is not fully hidden but never made explicit. Why rock the boat? On the reverse, when the closet doors open, does utopia sit on the other side?

Featured photos in text by Jinki Cambronero.