There is an old and particular connection between magic and language.

When magic is done, whether we’re laying curses on enemies, divining the future or summoning spirits from beyond, we understand that words should be said and the words should be significant. They should be in some old or secret language, or recited under special circumstances. They could be in the trochaic tetrameter of Shakespeare’s witches, or the liturgical invocations of prayer or hymn, but certainly magic shouldn’t consist of anything that you’re likely to say on the bus, or by accident.

Historically, there’s an entire occult philosophy of language and the place that it holds in the practice of ritual magic, perhaps most famously articulated in Cornelius Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia. The tradition has its roots in an intricate, syncretic web of religious, ritual practices and occult learning, but I will broadly summarise it here as belief in an incorporeal world of spirit that exists alongside our own, and that language is one of the tools we have to connect our material reality with the immaterial one. As we speak we create. So theoretically, the magician ‘does magic’ in our world by directly influencing the immaterial one.

As above, so below.

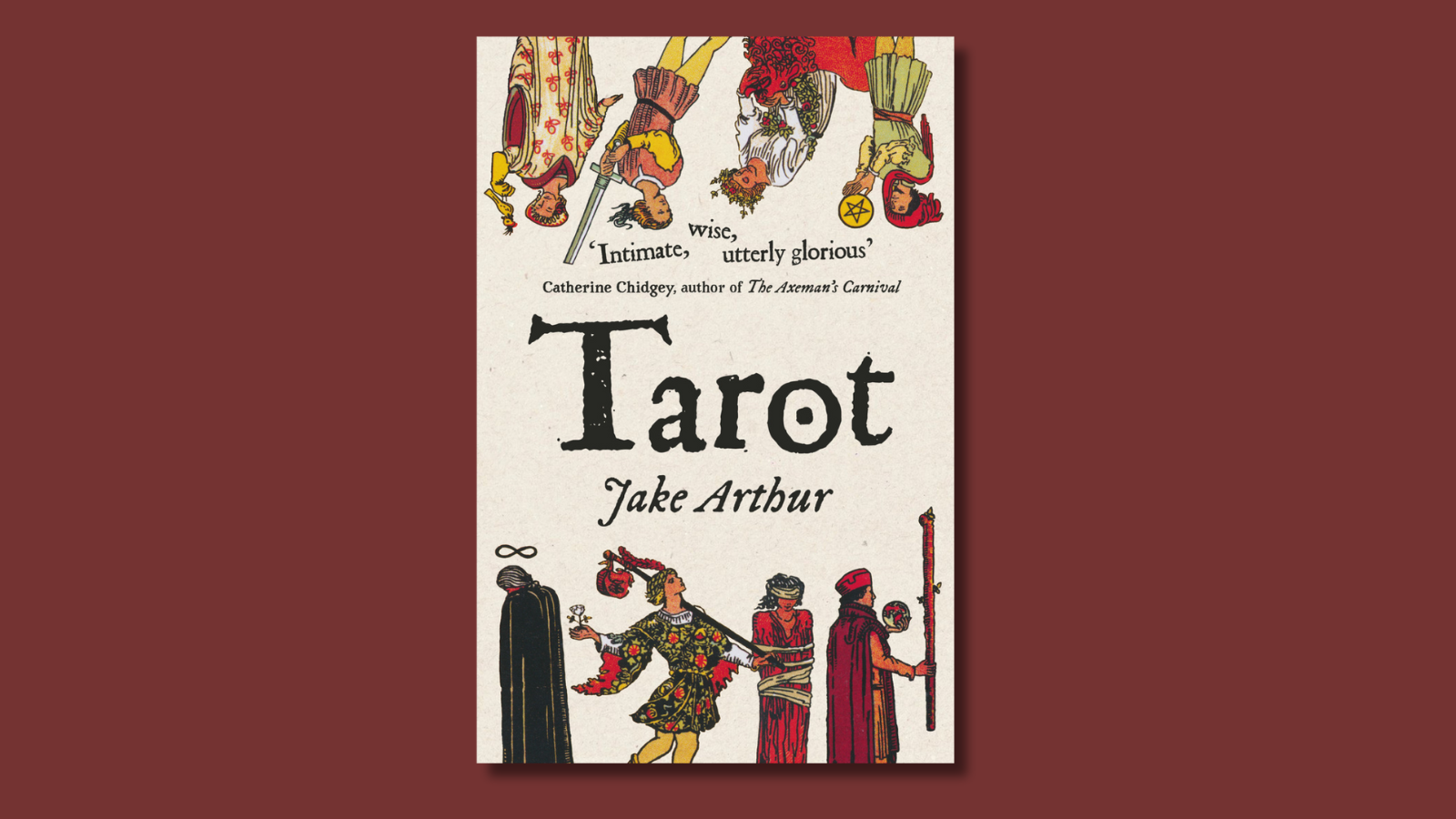

It is the occultist’s sense of duality colliding with the poet’s, the sense of two worlds connecting, that comes to mind when I read Jake Arthur’s glorious, enigmatic and curious second collection, Tarot.

Tarot takes its inspiration from the 1909 Rider-Waite tarot deck, which was, appropriately, a collaboration between artist Pamela Coleman-Smith and A E Waite, poet and occultist. The suite of cards they produced could be used for both card games and divinatory purposes, and Arthur’s collection likewise retains the tarot deck’s shapeshifting ability, moving seamlessly between worlds, at once playful, sage, and filled with dream-like poetic resonance.

From the first page, the epigraph of Arthur’s collection sets the tone in a register of between-ness

What should such fellows as I do crawling

between heaven and earth?

While the collection’s opening line in ‘Querent (I)’ acknowledges that we are passing between worlds:

My dear, you’re on a threshold

Once we cross that first line and enter the poem proper, we are brought into a world of wordplay and double meanings exaggerated by line breaks, as the tarot-reader takes us through a series of instructions.

(…) Sit down, have a cup

Of tea. We’re not above tea.

Leaves? Yes, but not today.

There is a light, punny tone to this section, but it has the added effect of giving the tarot-reader a bit of prophetic mystique, since we, ‘the querent’ are never entirely sure what was meant until we consider the line break. Until we’re looking back at what we’ve been told.

We can only begin when you look

At this plate and see the moon,

And in it your mother’s face.

The tarot-reader suggests a convincing metaphor for the state you have to enter to enjoy a bit of cartomancy, particularly if you’re as flagrantly un-mystical as I am. It requires a sort of loose, associative openness to be able to look at a series of character archetypes designed in 1909 and see your own life, and it’s an opportunity that Tarot revels in at every turn.

Equally, this language around how to read cards could serve as advice for writing and reading poetry: the careful attention to form, interpretation of images and the surprising associations that create something new out of language. The last lines of ‘Querent (I)’’ make this connection a bit more explicit with a play on the word ‘reading’.

Switch off that brain of yours.

It’s very loud. It’s like a very white light.

This isn’t surgery; this is a reading.

So, with the end of its introduction, the collection provokes the audience’s awareness that we are inhabiting the mystic, poetic world of ‘the querent’ and the real, material one as the reader of Arthur’s poetry collection, simultaneously.

Language and interpretation are constants of the collection, not so much a uniting theme as a heartbeat sounding under the surface. Perhaps because the collection is itself an act of interpretation, where each poem draws from the tarot deck’s visual references, its characters, themes, or divinatory meanings.

Pleasingly, every poem has two names, one that is more closely related to the literal action of the poem and one that references the card from the Rider-Waite deck that inspired it, as if each poem is lovingly balanced between the worlds of material and esoteric meaning. And like the deck, each poem revolves around a different character from an eclectic set of archetypes: an older woman having an affair with a young man, shipwrecked sailors, the mother-in-law of a failing marriage, Alexander the Great, and many more, each inhabiting their own jewel-like little space between worlds.

In ‘The spell or Knight of Swords’ (also published here on bad apple) the poem takes the knight archetype, that active combatant, and positions him as the lover-antagonist of the passive narrator. Language, of course, is the weapon of choice. There’s a passive heterosexuality to the narrator’s experience, “women’s names acted on me” while the names of men prove more problematic.

Men’s names, the Marks, the Toms,

The Jonathans, they didn’t even decibel,

Like, if a mouth could moan them

Mine wasn’t calibrated

But the encounter with the knight’s language is even more violent than the women’s ‘acting upon’ the narrator as we return to wordplay.

What exquisite traps he laid out

By being himself, swapping letters from

Won’t until it was Will, spelling no y-e-s

There’s a terrible sort of magic in it, the way that a lover can teach you the language of your particular intimacy. But here, the knight’s wordplay is a trap, a manipulation. This particular relationship takes us from the verbose flourishes of the poem’s beginning to those brusque single syllables and blunt double entendre of the end.

He worked on me like a sentence

He just had to finish.

Other poems are more overtly drawing from the literal image on the corresponding tarot card, as in ‘The robin, or Nine of Pentacles’. The poem begins with the image of a woman holding a small bird on her finger, while the narrator (and reader) is positioned as viewer. Though at first we luxuriate in the image as image, witnessing “the beautiful” and “the diaphanous”, “Not flesh, a vision”, the poem soon begins to take a less romantic and more embodied turn.

But consider: birds have very small brains.

They are like a cashew nut, the meat of an acorn

Here the narrator interprets the image. An act of reading that cuts through the mystic artifice of the scene with biology, as the bird transforms from still image into wild and breathing life. For a moment, the poem makes a case against the bird’s confinement in the poem, in the “using up of the bird’s short life”. Until it ends with this,

But, if it is all as absurd as I say,

Why then does the girl look so beautiful,

And the bird so proud?

Tarot is always deft in its movements between the mystical and the material, the poetic and the literal. Though the narrator seems initially to have reached a conclusion about the meaning of the image, the last word they have is used to doubt themselves in such a way that creates space for resonance, emotionality, and wonder.

All this highlights Tarot’s generosity. There is a distinct lack of didacticism on the topics of fortune telling or linguistic interpretation, instead, it consistently offers its questions to the reader, revelling in these moments of duality and multiplicity. Thus, the two worlds are constantly mingling, creating a space where the mystical is rationalised as often as the rational is mystified and where language is ecstatic as often as it is scholarly. It’s a kind of magic, to create and interpret with language, to summon fat babies and garden birds at will.

Lithe leveret!

More arms than two

In your mother’s fore

Swaddled naked, in fat

& soft bones

So when we come to the very end of the collection, ushered back into reality by the tarot-reader taking a second turn on centre stage in ‘Querent (II)’, it seems inevitable that the collection leaves us where it does: in an open space between possibilities, with an invitation, a reading and a query.

There’s no single voice.

No fact is binding.

Watch me roll the dice again.

That four: isn’t it also one, three, six?

Featured image courtesy of Te Herenga Waka University Press.