I wasn’t sure what to expect from kitten.

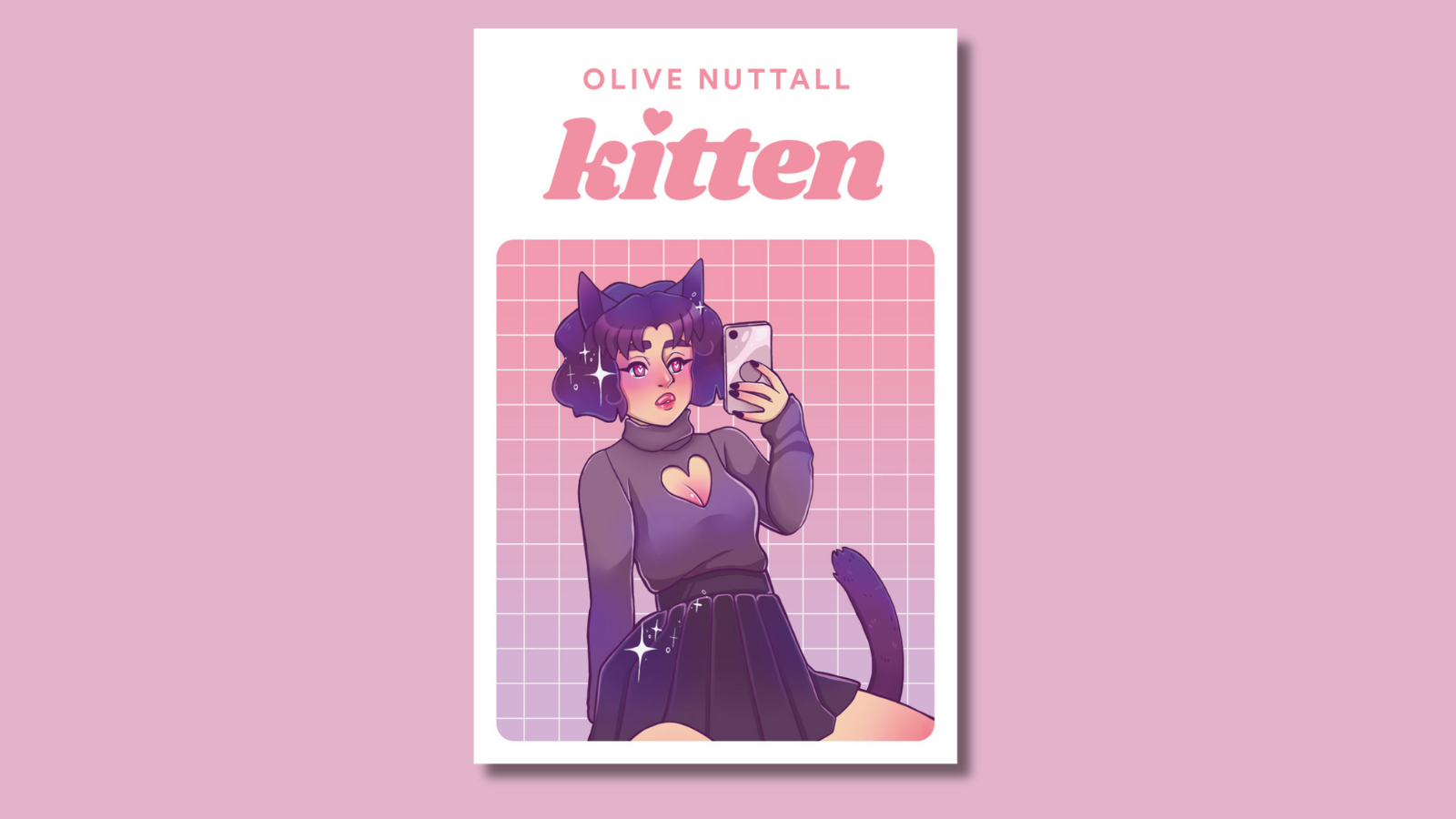

When I received it, I studied it for a few minutes, feeling the satin finish of the crisp white and pink cover. The title and catgirl are printed in gloss, catching the light as I held it up. I took in the shiny e-girl overkill blush on her cheeks and cleavage, the sparkles and shine on her hair and lips and hentai-trope heart pupils, and the Picrew-reminiscent gradient grid of the background. Real terminally online lewd girl vibes, right? Makeup and filters and avatar makers and the glossy art and the glossy print and the artificiality of it all—cute beyond belief, provocative, and a little unsettling.

I considered the front cover, turning it over in my hands. I considered the blurb at the back, which opens and closes by describing kitten as a love story. Everything between open and close outlines something turbulent, never named: family trouble, historical trauma, ghosts coming back to roost. It’s certainly not the kind of love story I read as a teenager, when my grandmother unabashedly left her Harlequin large-print romances around the house. I wasn’t sure if it was going to be a love story at all, but I wanted to find out.

Rosemary’s perspective on the world is strongly formed from the first page, almost My Immortal-esque at first in its self-consciousness. She begins the first chapter on Tinder (bisexual Tinder, she clarifies), immediately dissecting its dynamics and her potential matches with cutting, self-deprecating wit. Her voice is immediately both familiar and distinct.

It’s a bit like getting into a pool when you know it’s gonna be cold—the best way to adjust is to simply jump into the deep end. Rosemary is a blur of rapid-fire judgements, the kind you have to make on Tinder and in general as a young trans woman. She’s pragmatic about being a horny disaster. She’s hungry for insight into others, filtered through her over-awareness of herself:

Some girls start Instas as the beginning of their transition, but if you scroll back on other girls, they’ve kept all the photos from their boymoding life. I could never, to be honest, but I’m also kind of jealous that they can. Like, how come they aren’t ashamed?

Page fucking two continues, right after that, like this:

Anyway, I love matching with the girls. It’s always a revelation. Not only do I have sisters hidden all within an 80km radius of my bed, they might also want to commit incest with me.

That excerpt sets the tone for the book remarkably well, for Rosemary’s flippant yet carefully performed construction of herself, even as a narrative in her own head. The things she makes light of—the things that are just obvious to her, from the life she’s led—these papered-over pieces form the shapes of the novel to come.

“She’s a car crash, but not the kind where someone’s fallen asleep at the wheel. She’s speeding ahead with full awareness that her brakes have been cut, and she’s probably the one who snipped them.”

Rosemary continues inexorably. (I’m reminded of the English dub of Haikyuu! including the hilarious line He’s like a horny tornado. That’s the vibe.) She’s a car crash, but not the kind where someone’s fallen asleep at the wheel. She’s speeding ahead with full awareness that her brakes have been cut, and she’s probably the one who snipped them. As the trans child who moved to Wellington, Rosemary ploughs back into a mass of family dynamics in Kirikiriroa and finds herself, as many of us have, flung back in time. Previously locked doors rattle free, setting loose their monsters to meet the people we’ve become in the time we’ve been away.

I’m struck by how dense kitten is. It drags me onward, tumbling through paragraphs built from single run-on sentences that somehow carve the carcass of a complex family dynamic into precise parts. It’s about sex, in ways that are lurid and earnest and unabashedly queer; it’s about sexual violence and intergenerational trauma and blurred edges and what happens when someone is honest about who they are and what they have been. It’s about So what if I’m fucked up. I know that. Maybe I deserve the world anyway. And Rosemary does deserve the world, as all of us do.

Rosemary’s certainly not a perfect protagonist. She’s boldly voiced, and it’s honestly offputting at first—her overly introspective thoughtlessness is a combination that is both very recognisable and very hard to watch in someone else. I read a tweet years ago which said that trauma makes you selfish. It turns you inward so all you can see is your own pain. I’ve felt that in my own life, and seen that in so many trans people I know, acting out and fucking each other up in a thousand ways, and I see that in Rosemary. From the flattened wasteland Hamilton is for her through to the way she treats her Tinder matches, she’s selfish. The fucked family dynamic and the ghosts behind it worry at her like a paper cut that just won’t stop stinging, and it sucks her away from full participation in her life for much of the book.

Nuttall’s prose is irreverent and compelling. There are words in here that some readers will wince at—whether that’s the incest joke, slang like gock, or reclaimed slurs—but they’re real and they fit perfectly into sentences created to house them. Intentionality is the word I used most, discussing this book with my wife: the pop culture references and white girl weeaboo stuff makes me restless. Rosemary’s thoughts fly from family to fucking to trauma freefall and back again in a distinctly queasy way. There are moments where the choices she’s making or the situations she’s found herself in set me entirely on edge. It’s all lovingly crafted, building up a person who doesn’t have to feel likeable to feel real.

So too Rosemary’s taste in partners is presented as completely natural and obvious: “his PhD and receding hairline”, “xyr fat body and xyr butch mullet”. There’s no shame or self-consciousness here, where it’s a constant thread throughout Rosemary’s perception of herself: her loving of masculinity and of transmasc bodies, in particular, is perfectly straightforward and carried without conflict. T4T, Rosemary says, directly referencing Torrey Peters’s seminal novella Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, and T4T it is.

“Maybe it sucks when people call it brave because they don’t get it and it’s just what you have to do. But I think Rosemary’s brave, and all of us who have been there are, too.”

Rosemary is so completely, excruciatingly comprehensible. She’s working shit out about herself in real-time, lapsing between flashbacks and present sexcapades, and she’s doing it with the kind of attitude that . . . Well, I don’t want to call it brave, because every trans person with trauma has heard that one, but that’s the attitude she’s got. Fuck if there’s anything else to do but press forward. And stop drinking. And fuck people you shouldn’t. And figure shit out along the way and hope you don’t burn too many things down as you push through into your very own future. Maybe it sucks when people call it brave because they don’t get it and it’s just what you have to do. But I think Rosemary’s brave, and all of us who have been there are, too.

When I stumbled through the closing chapter and back out to the back cover, I stared at the blurb again. Nothing in this love story is straightforward, it opens. I think the love story at the heart of this book is maybe the most straightforward thing about it. Maybe it’s not normative in any way. Maybe Rosemary would be entirely unintelligible to anybody looking for something normal. But the love story is tender and genuine precisely because it’s so uncomplicated. At least in relation to all the complications of childhood friends and extended family and casually transphobic shopkeepers and exasperated bosses and harm and trauma and maybe-trauma and trauma-but-everyone-has-it-and-that’s-worse and people who want a kind of person that you’re not sure it’s possible for you to be, not now, not ever. It’s care, given and received. Asymmetrical and balanced all the same, in the only ways that matter. If anything, it might be a little brief, outlined in broad strokes that might be too efficient, but I think that’s a side effect of that power struggle with everyone and everything else being such an ordeal. It’s almost too easy, perhaps, to finish the book where it ends.

I turned back to that beautiful cover. Rosemary shows an anime catgirl to her family, once, struggling to explain the topic of her potential master’s thesis. She’s trying to put together something about trans womanhood, filtered through pleated sailor skirts and men’s expectations and orientalism and objectification. Her sister points out that she dresses like the slutty catgirl, her mother notes the tiny skirts on even the butchest Sailor Moon characters, and the point is lost before it’s even made. But the girl on the cover isn’t looking at me. She’s focused on the phone in her hand, on how she looks on screen. Making and remaking herself: How do I want to be seen? As Rosemary says at another point: “I wanted to look cute and sick […] like an anime girl with tuberculosis.”

Promiscuous, airheaded, fuckable. Broken and honest and real—a woman, surfacing in a sea of expectations and societal dysfunction, finding her footing. kitten really is a love story, with all its self-absorption and its ragged hems. It’s about coming to terms with being known for real and still deserving love.

This book’s dedication is for the girls. That’s really all there is to it: kitten is for the girls who know how it is. It loves them back, in all its hot-mess sincerity.

You can purchase kitten from your local bookseller, from BookHub, or directly from Te Herenga Waka University Press.

Featured photo by Pluto (illustration) and Todd Atticus (cover design) via Te Herenga Waka University Press.