What better way to spend a Tuesday night than to settle in and explore the death of a gay man?

Not actual death, but Gay Death. That is, the altogether too-popular myth that gay men are no longer desirable or fun by the time they turn 30. It’s an insidious concept unique to queer people.

For us, and especially gay men, turning 30 is a little bit different. Yes, there are the same arbitrary milestones everyone deals with — have you bought a house? Are you married? Maybe not kids, but dogs? But more than that, it’s about what we perceive to be ‘gay culture’.

Drinking, partying, drugs, unprotected casual sex, working out, bottom-friendly diets — all of these things are typically summed up into a somewhat narrow idea of what gay culture is. And maybe that is gay culture or at least a part of it.

Most of these things are not (necessarily) bad. What’s bad is that there’s an idea that when you turn 30, you’re too old to participate. Or that once you’re 30, you’re not welcome in gay party spaces (of which there is an absolute abundance in Auckland, I’m sure we’ll all agree).

The point is, Gay Death is an idea that basically says if you’re over 30 you can’t party, you can’t fuck, and you should sit down and eat your keto cake.

Gay Death Stocktake is a reflection on turning 30, on anxiety over the concept of Gay Death, feeling you haven’t achieved or that you aren’t prepared to be ‘old’. Though written by Nathan Joe, and centred around his own life and anxieties, each evening of Gay Death Stocktake stars a different performer.

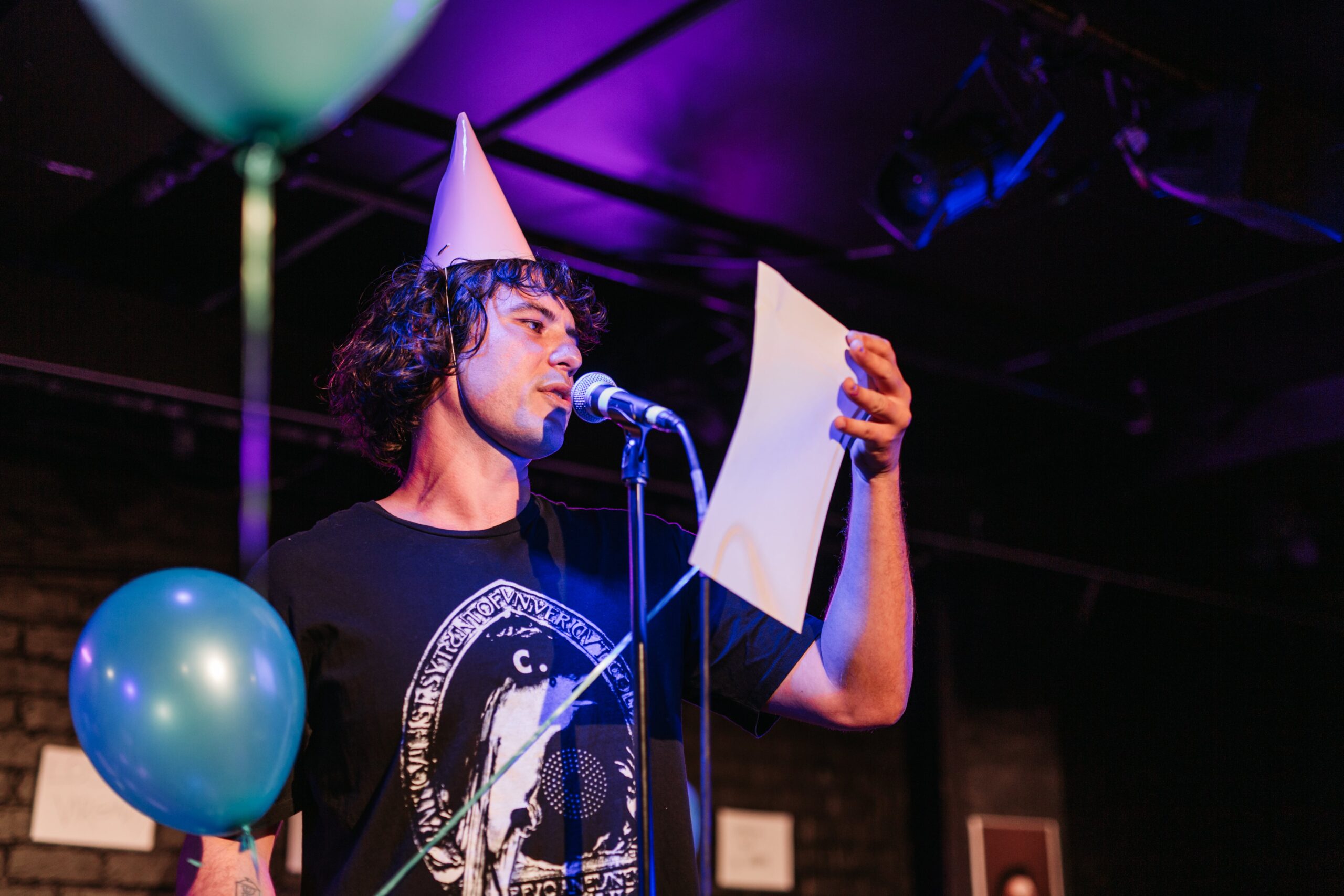

On opening night, this performer was Samuel Te Kani, 32, a freelancer (or in his words, unemployed) writer and generally interesting gay person, whose Twitter likes are, frankly, a very good time.

No director, no rehearsals. Samuel’s job was to read and perform 30 tasks scattered throughout the room — most of them a musing on being gay and 30.

The interesting thing about writing a deeply personal stage performance and asking someone else to perform it for you, without changing any names, without direction or rehearsals, is that the performer is going to bring to it whatever they want. Your words will always sound different coming out of another person’s mouth.

In this case, Samuel was very aware that he wasn’t speaking his own words (except when prompted to). He knew Nathan was in the audience and would, at times, address him, responding to things Nathan had written with surprise or playful judgement.

Samuel brought almost a kind of flippancy to his performance. He saw the 60-minute time box as a competition and would scamper hurriedly to find each task and speak as quickly as his breath would allow. At times he wouldn’t seem to engage with what felt like an opportunity to be vulnerable but instead would respond with something masked in humour.

At one point, he was asked to call someone and tell them that he loved them, a task which he almost refused to do. The recipient didn’t pick up. We moved on.

Many of his answers centred around sexuality — his first buttplug, his first fist, his first bottle of poppers — while Nathan’s texts were broader, sometimes speaking about personal accomplishments, romance, finance, body image, race and yes, sex.

But here’s the thing — I may sound like I’m saying all of this negatively. But the contrast between Samuel’s performance and Nathan’s words actually told, to me anyway, the most compelling story there. As if Samuel’s response to many of Nathan’s lamentations was “So what?”.

Samuel spoke with an irreverence for the list of accomplishments people ‘need’ before 30. All of these milestones are built up and decided on by a heteronormative capitalist society, but are they really relevant to modern queer life? Do they need to hold any space as measures of our success?

I think this speaks to the myth of Gay Death. This monolithic, terrifying concept of losing all desirability at 30. It speaks to the myth of some unified gay experience. Gay Death relies on a singular experience of gayness — but the truth is that while many gay people have had very similar experiences of a lot of things, the way we assign our value is not universal. Rather, we all have deeply individualised experiences beyond our gayness, that shape our gayness. And fearing the big three-oh is just the fruit of a few narrow outlooks.

I spent much of my late teens and early 20s being chronically ill and was lucky enough to find queer, supportive friends outside of the usual gay groups. All of my friends were older than me already, on the higher side of 20, and largely women.

I’m now 27. I remember at 20 musing that all the hottest celebrities were 32 (thanks Aidan Turner). And, in the age of the glorification of the Dad Bod, and the ironic-but-not-really normalisation of calling guys ‘daddy’, are we really still talking about becoming ‘unhot’ at 30?

On the flip side, my partner is a gay man who did all of the usual gay culture stuff, or at least was around it. He told me after the show that, when he was in his early 20s, Gay Death was something he and his friends were genuinely afraid of. Now that he’s 32, he thinks the idea is ridiculous.

My point is that Gay Death is a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s feared by a culture born from young gay men, and it’s something only young gay men really believe in. Gay Death Stocktake is a successful examination of this.

Samuel brought new beauty to the script through his irreverence, dismissiveness and unapologetic joy, and the way they challenged Nathan’s words and beliefs. In just 60 minutes, Samuel and Nathan both showed the sheer variety in experiences and viewpoints within the queer community — even in the small slice that is just gay men in their 30s.

As a performance, Gay Death Stocktake was messy, but that messiness didn’t feel inappropriate. After all, what’s messier than being gay a man in your 20s? Maybe being a gay man in your 30s. Either way, it’s a hell of a lot of fun.

Each night the performer changes, and I can only imagine how a different performer might completely change the message and the tone of the show. There’s infinite potential to view this show over and over again and take away something new each time.

Without giving too much away, the performance ended with a message of love — a reminder that our achievements are more than arbitrary capitalistic milestones, and that we have many more than 30 years to make art, do drugs and take a fist up the ass.

Tickets for the remaining performances of Gay Death Stocktake are available from iTicket.

Featured photos by Ankita Singh.