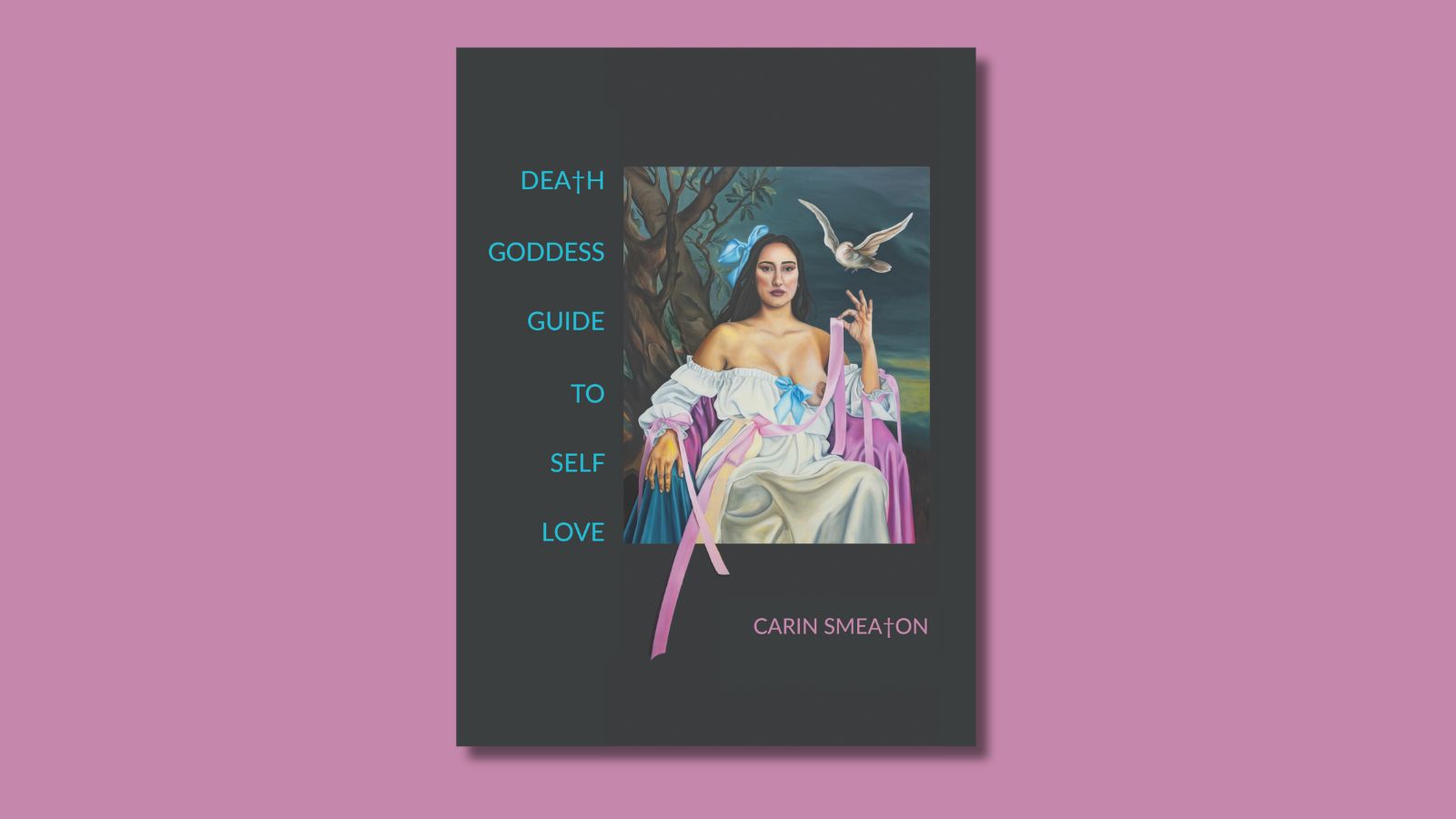

Carin Smeaton’s latest poetry collection Death Goddess Guide to Self Love says screw you to colonial poetic tradition and poetic tradition in general. the words guide to in the title evoke either intentionally or accidentally if the difference between those two things can even be established anyway the words guide to in the title evoke a self-help book for dummies and in this context the dummies are you the reader any Pākehā institution models of traditional language models of organisation systematisation classification. utilising a written critical analytical framework at all to explore a book like this may well be a fool’s errand but let’s try. the poetic provocation of Death Goddess Guide to Self Love is to deconstruct all the constructed ideas we ordinarily carry about and through poetry, though for Smeaton these notions and subversions seem like effortless byproducts of the voices of her poetic speakers. for instance the book opens with “Nga whakawhetai” [sic, printed with no macron], a section that in the western poetic context tends to come at the end of a book; its placement here in Death Goddess Guide to Self Love prioritises in classic Māori fashion an acknowledgement of the whānau kares hoas tūpuna tīpuna that come before us and make us possible. poetry doesn’t just come from te kore, kāore! with ngā whakawhetai and whakataukī to welcome us in, Smeaton’s collection then traverses three sections, Book of Alice, Book of the Dead and Book of Sina. Smeaton uses lots of alternate characters beyond ordinary literary fonts, for instance the “t” in book of the dead becomes a cross: Book of ✝he Dead, among others. take that, colonisers of language! the same week i started reading Death Goddess Guide to Self Love a friend asked me and another friend if we thought that, after all, grammar was inherently classist, and without missing a beat we both said āe! of course it is, there’s no doubt about it, like etiquette and every other constraint upon behaviour it sets arbitrary standards and if we understand that meaning is flexible anyway then what? after all isn’t poetry the form with the most flexible of meanings? perhaps not: at its strongest Death Goddess Guide to Self Love trades in firm narratives, as in the excellent diss track poem ‘kids 1n 5upermarke✝ j0bs’, which in its entirety reads as follows: “o.m.g // R u sure u lov him? / R u sure u wanna stay wit him? // R u really gonna scrap uni 4 him? / Wat was it u was gonna study anyway? // Did he ever have any aspirations / Besides owning his own new world // & a 3 bedroom house in town? / It looks very spacious u know // expensive // U could have a couple flatmates / stay to help pay off the mortgage // The tender one will try to fuk u / When ur drunk and tired // It’ll be the ultimate distraction / u been waiting for” like ok Carin brutal??? The firm narrative here is one of disdain, this is recognisably the new zealand we live in of skyrocketing property prices skyrocketing supermarket prices everybody just trying to stay afloat. the complexity of this poem comes when attempting to actually read, to actually analyse just what is going on with the direction in which the ire of the poem is facing—is the speaker jealous of the couple at the centre of the poem’s narrative, or merely disdainful? is the speaker themselves missing out on “the tender one try[ing] to fuk” her? an easy reading of this poem suggests an overt resistance to home ownership to new world to scrapping uni to being in love like this but a more complex reading suggests the speaker has all sorts of complex feelings and jealousy tied up in what they’re saying. take, for instance, that line break: “u could have a couple flatmates / stay to help pay off the mortgage.” the enjambment here means that the line “stay to help pay off the mortgage” could refer to the person in the relationship, staying for no reason other than to help pay off the mortgage, as opposed to the flatmates themselves. Smeaton effectively wields and expands the potential poetic meaning even in locked down narratives throughout this collection. it’s a collection of dizzying end stopped lines making declarative statements that are less simple than they first seem, like “he gets a license to glide high” or “Mary D says we don’t stay young 4 long” or “our blood is hidden like shame.” Smeaton trades in such declarative outrage to squeeze in music through rhyme through alliteration through the expansion of language made possible through its contraction away from formality “U cd say U cd say U cd say ur tru spellbound” in the same way that any reader of Smeaton’s poetry must be willing to let meaning collapse for a little before it can emerge again, go through the woods with these ironic femme speakers only to pop out on the other side of irony with a view of something earnest again with a view of something that can be expressed declaratively without a hint of irony because declaration will belong again after all that to us to those of us that have suffered from it before.