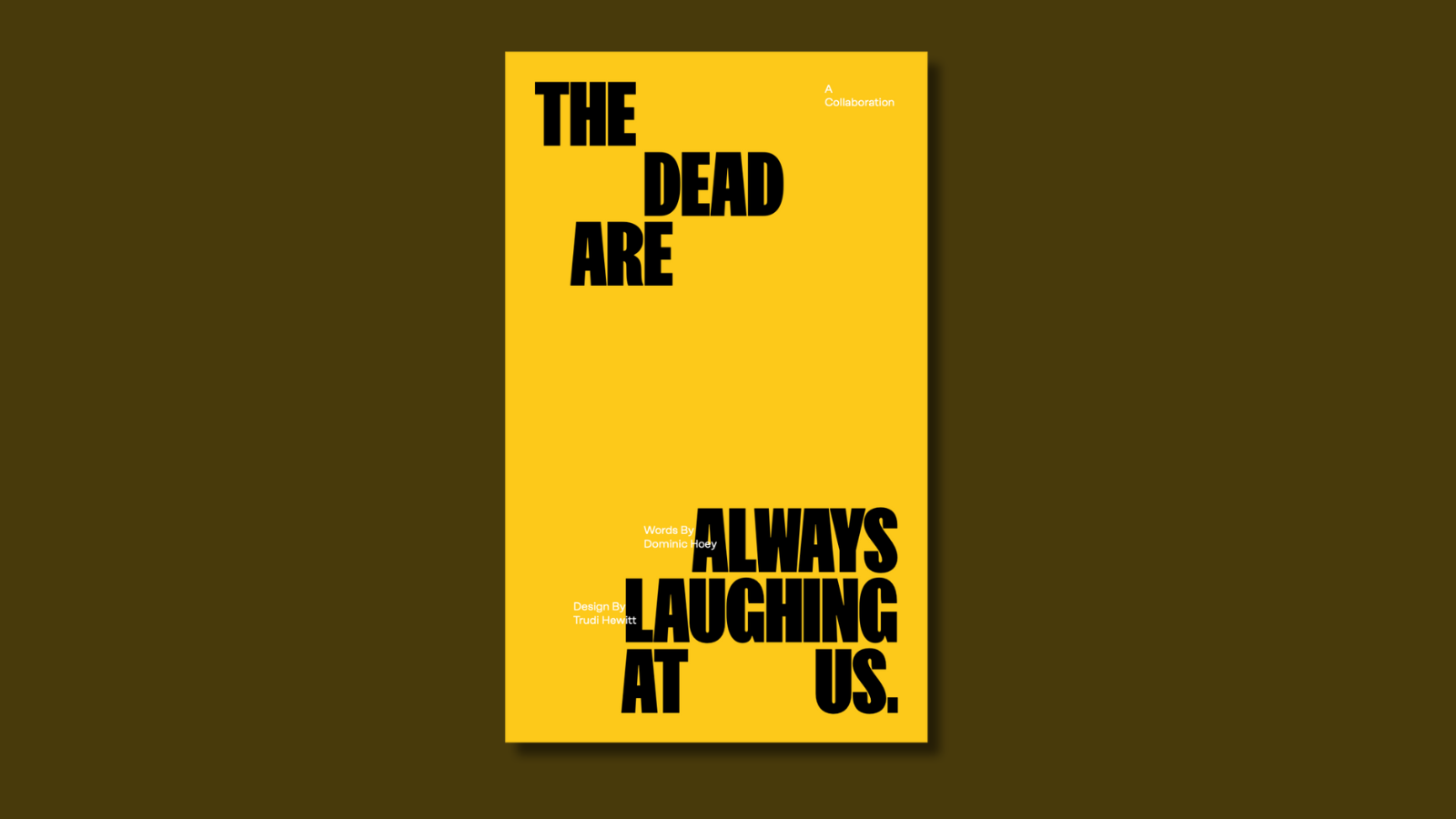

Hot on the heels of 2022’s Poor People With Money, Tāmaki Makaurau’s most subversive wordsmith Dominic Hoey is back on the scene with his latest poetry collection, The Dead Are Always Laughing At Us. Tackling themes of love, grief and socio-political disenfranchisement in the claustrophobic setting of the pandemic lockdowns, Hoey articulates a swathe of emotions with clarity and concision.

Collaborating with designer Trudi Hewitt, the visual and written mediums combine to present a striking and easily accessible piece of literature that doesn’t require institutional validation or any particular degree of intellectualism for readers to resonate with. Making simplicity stylish and proving once again that he really is bringing ‘Poetry to the People‘, Hoey’s latest collection is a modern, engaging and genre-defying work for anyone who’s feeling a little lonely, a little in love, or a hell of a lot pissed off.

Devon Webb (DW) speaks with Dominic (DH) about the new book, poetry at large and going on a national tour with Dead Bird Books poets.

DW: I believe this is your first book in which you collaborate with a designer, with a specific intention regarding how your poems look on the page. Was there anything that drew you to Trudi Hewitt in particular, and how did you find the collaboration process? Do you think it’s had an impact on how you’ll approach your writing in the future?

DH: I’ve done two books with tattooist, musician and amazing weirdo, Josh Solomon; Party Tricks and Boring Secrets and Bad Advice for Good People. Josh essentially worked as a designer with both, using scissors and paper rather than a computer.

But I think this is the first time I’ve worked with someone where design is their main skill set. It was really different in the sense that Trudi took a lot of the writing in directions I wouldn’t have expected. I’d actually love to do more of a traditional poetry book in the future. Like 20-odd poems on one theme. But we’ll see what happens.

DW: In the introduction of the book, you speak about wanting to make your work as accessible as possible. I think this is such a wonderful and important approach, and ties in with how vocal you are about navigating dyslexia and disability as a writer. Can you tell us a little more about that, and the way you and Trudi used space, shape and simplicity to create a unique presentation of poetry? Is there anything you’d like to say to others in the industry regarding how they can contribute to this accessibility?

DH: I remember years ago when I was still rapping, I’d do poetry gigs sometimes on the side. But most of my mates wouldn’t come cos the shows were either really conservative or just absolute madness. But my one mate would attend every show. Ones at the uni where people are sipping tea and nodding their heads, ones at bars where everyone’s so drunk they can barely get on stage.

And I remember performing one night and afterwards he was like, I love it but I don’t know what you’re talking about half the time. I remember thinking why the fuck am I writing shit my mate doesn’t understand to impress people who I have nothing in common with.

So from that point on (I think this was 2006) I really put accessibility at the forefront of what I do. There’s no reason you can’t have maximum emotional impact and still have subtext with really simple writing.

In regards to working with Trudi, I liked the idea of someone who wasn’t sure if poetry is ‘for them’ picking up the book and opening it and seeing a page with some big statement on it, or a beautiful couplet. and then being drawn into the book.

I think it’s two-fold in regards to the industry. There are such limited funds and resources that people often don’t have the capacity to think about accessibility too much. On the other hand, there’s heaps of people who can’t see how inaccessible it is. So they don’t think there’s an issue, ya know.

DW: This is a book that very much feels like it was born from the lockdown era—it has a sense of claustrophobia to it, the idea of being trapped in a house or a city or a screen, with a mania that seems to degrade towards the end, especially in the final poem. How do you think the isolation of the pandemic affected your creative thoughts and processes? Did you notice a distinct shift from your pre-pandemic poetry?

DH: In some ways, it was super positive. I finished Poor People With Money in lockdown and wrote Bad Advice For Good People and a proposition for a TV show which is going to be my fourth novel now. At the same time, I was meant to do all this overseas touring in 2020 which would have really lifted my career to another level.

My friend Todd died during one of the lockdowns, and this changed my writing more than the pandemic itself. I have three or four people in my head who I’m always writing for, and he was one of them. So in some ways, it’s harder to write now. Like the launch of Poor People without him was so strange. But at the same time I also feel a pressure to succeed, cos I know how proud he was of me for getting to do this kind of thing.

DW: It’s a very thematically dense collection, which is interesting in contrast to its minimalism in terms of design and the brevity of many poems. I found the juxtaposition of love and grief really interesting, especially in the way these poems were entwined through how you’d chosen to order them. Was that an intentional choice? And how does it feel, to pen these deeply personal poems and sit with them throughout the curation process before ultimately releasing them into the world?

DH: I think the order was helped a lot by my mate Liz Breslin. She edits most of the Dead Bird Books releases. But I think Trudi also changed a few around for design purposes.

It’s weird with putting personal shit out there. In some ways, it’s just something I’ve always done. But I think especially with Todd’s death and the poems about him and our relationship, I always worry that I’m not doing his memory justice.

DW: There are strong themes of anti-capitalism and anti-institutionalism running through all your work. Do you have any advice for other writers who are pursuing their craft independently outside of the institutional roadmap, and how to persevere amid the scourge of capitalism in which the arts are fundamentally under-supported?

DH: I really feel for young writers and artists in general. Like, when I was young it was hard for sure. Don’t believe people who talk about the artists’ benefit and how amazing it was. It was impossible to get on and they were always trying to kick you off. But at the same time, you could scrape by and make art most of the time. Especially if you grew up poor and were used to eating shit and not having nice things.

I think the main thing is either find or form a community. There’s power in numbers. And learn to do it all. Book shows, write press releases, contact media etc. Don’t sit around waiting for anyone else. Cos even if you do find someone who will do everything for you, they often don’t know what they’re doing, and no one cares about your work the way you do.

DW: As a Gen Z poet from Tāmaki Makaurau, I’ve personally experienced the impact you’ve had on the younger generation. I think your use of Instagram is a big contributing factor to this, in the way it’s increased the reach of your poems and the messages of frustration and disenfranchisement that many of us feel in the current socio-political climate. How do you think this accessibility—to circle back to a previous theme—has affected your career, and are you surprised by the responsiveness and passion your work has inspired?

DH: That’s really humbling. I never think anyone notices what I’m doing, especially young people.

It’s funny cos I think the politics my friends and whānau always had have become popular with your generation. Like in the ‘90s when I was young, being into Marxism, activism etc was seen as weird and very niche.

So I think that has played a big role in my work resonating with more people. The thing that’s always the most meaningful is when someone says they picked up the pen after reading my work. Cos I had those people in my life, and to be that for someone else is really special, and not something I ever take for granted.

DW: On a similar note—you regularly teach writing classes and have worked with various youth organisations. Do you think this proximity to the community has impacted your writing or inspired you in any way? Is there anything you particularly love or that motivates you when it comes to supporting others?

DH: For sure. I’ve learnt so much working with rangatahi, and the classes I do with adults, whether at the City Mission or my ‘Learn To Write Good’ classes. I was saying to a mate recently that I actually enjoy teaching more than performing in some ways, which I never expected.

There’s nothing better in life than helping people, really connecting with someone over words and performance. Writing saved my life in no uncertain terms, so I want to help it do that for other people.

I feel really blessed to have the knowledge and skills I do. And I feel a responsibility to share them with as many people as possible, cos when I was coming up all I wanted was someone to be like “Here’s how you do this or that technique,” but there wasn’t really anyone doing that for people who didn’t go to uni.

DW: This is your second poetry collection, after I Thought We’d Be Famous in 2019, and you also recently put out your second novel, Poor People With Money. Are there any particular ways in which you’ve evolved along the way or lessons you’ve learned throughout these years immersed in the writing and publication processes?

DH: It’s actually kind of my fifth. But the other three are out of print and the first one sucked!

I just try and get as simple as I can with my writing. A lot of the poems are jokes and absurdist ranting, but even the really heartfelt ones that have beautiful turns of phrase and images, I try and keep them feeling like we’re just having a chat and I happen to know some flash ways to talk about my feelings.

DW: You’re taking Dead Bird Books on tour to celebrate the release of this book alongside Neither and Talia by Liam Jacobson and Isla Huia respectively, both also published this year under the Dead Bird banner. What’s it been like collaborating with Liam and Isla on these projects, and what’s the vision for translating your written works to live events? Any particular aspirations or anxieties?

DH: Liam and Isla are the future of poetry in this country. I have no doubt they will both be household names. As far as working with writers, it’s usually pretty chill. We basically run Dead Bird as a public service, so we let people know this is a very low-stress organisation. Both Liam and Isla already had such a strong collection of work it didn’t take much to pull it together.

We’re doing a set each. I’ve got some new poems, a couple of old ones and I might also share a chapter from my new novel which is almost finished—set in 1985 Grey Lynn, the day after the Rainbow Warrior bombing. I’ve been performing since I was 12 so I don’t really get anxious. I often feel more at home on stage than off.

DW: Are there any particular artists that have inspired you throughout your career, or who you might like to collaborate with in the future?

DH: It changes all the time to be honest. Mostly just my mates. People like Tom Scott, Tusiata Avia, Liam Jacobson and other friends who might not put their work out in public but are quietly making amazing shit in their homes. I also get lots of inspiration from films, particularly ones with sharp dialogue and solid plots.

DW: What’s next for both you and Dead Bird Books? Do you have any plans for 2024? And how do you feel about what you’ve achieved so far?

DH: Next year we’re putting out books by a bunch of amazing poets. We really want to grow it.

We’re also looking at starting an offshoot that will print really limited runs of experimental works or books by writers who have a limited audience but need to be read. It’s only really dawned on us that we’ve set up this press that is having an impact on readers and writers alike this year. I feel very lucky to be able to help people put their work out there and have careers, ya know.

The Dead Are Always Laughing at Us is available at independent bookstores and on the Dead Bird Books website: https://www.deadbirdbooks.com

Tickets for the Dead Bird Books tour featuring Dominic Hoey, Isla Huia and Liam Jacobson are also available on the website, with dates listed below

30 November: Golden Bay, Mussel Inn, 7pm

1 December: Ōtautahi, Little Andromeda, 7pm

2 December: Ōtepoti, Yours, 7pm

8 December: Tāmaki Makaurau, Wine Cellar, 8pm

9 December: Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Meow, 7pm

Dominic Hoey can be found on Instagram at @dominichoey.

Featured images courtesy of Dominic Hoey and Dead Bird Books.