After the show, I’m standing outside with my Asian friends, joking about how all Asians wanna talk about is death.

If it’s true, humour me: what preoccupies Asian people about death? Maybe it’s not death exactly, but the endless possibilities and fragmentations of how your life could have turned out. The little lives to fantasise about, and the little deaths they receive. A preoccupation with death is more a preoccupation with mythmaking and the ‘what-ifs’—what if you lived somewhere else, what if you weren’t gay, what if half of you was somebody else, what if you weren’t you at all?

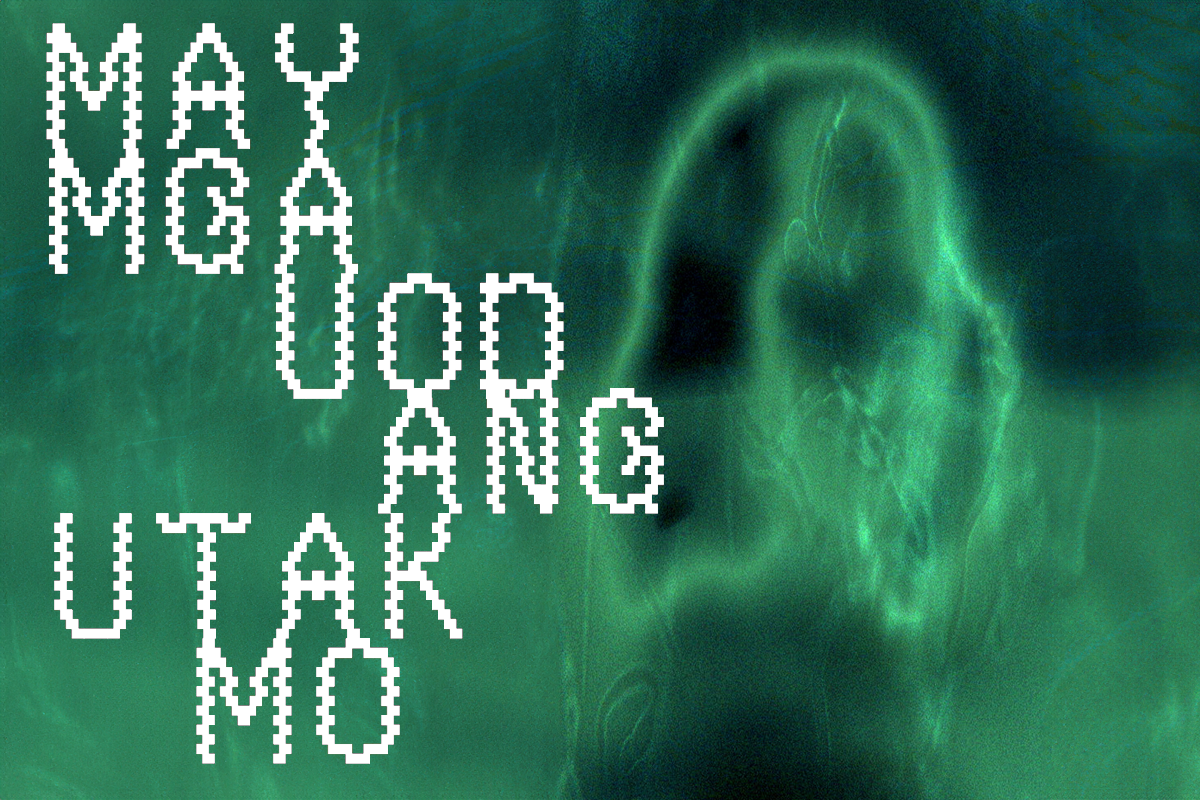

May Mga Uod Ang Tak Mo explores every last what if, a multiplex of grief in all the ways it leaves you bruised, broken and naked. The show is Sean as himself reading his father Graeme’s self-authored eulogy “because he didn’t trust anyone else to write it,” while challenging and scrutinising every sentence in its grand claims to surrealist ends. As Sean scrutinises, a voiceless masked wrestler (Tyler Kōkiri aka KŌKIRI) fights Sean to get to the end of the eulogy, slamming his head against the flat wooden top of the podium, and Sean is forced to reset and pay his respects to the ‘cadaver’ that was once his father.

The wake that never ends becomes the never-ending shape of grief. At a late point of the work, Sean recalls a viral clip of Andrew Garfield speaking on a talk show about his mother’s death and subsequent grief as a beautiful reminder of all the love he has for her. And it’s a beautiful sentiment, but not one shared, exactly. In earlier parts of the play we hear about Graeme’s alcoholism and party-boy lifestyle that kills a friend in a car accident, his treatment of his first wife and batch of children (who Sean reminds us are not present at the ‘wake’), and the dubious terms of meeting Sean’s Filipino mother that leave Sean calling himself a “little fetish baby”. These faults of Graeme lay bare his penchant for mythmaking (#MythmakingForWhites), and the great paradox Sean has to play out of why it still hurts to miss such a shitty person.

Do the faults of the father pass to the prodigal son, too? May Mga Uod Ang Tak Mo’s doomed-to-repeat format works and works away at validating Sean’s self-hating tendencies: comparison is the death of joy! This tension in the mythmaking of self asks, what lies do you hold onto to be okay with the reality of the choices you make and keep living? It is here that the show beautifully explores the scummiest and strangest corners of the internet, where self-flagellation and cruelty are the only accepted currency. At various parts of the show, we see projected messages from well-meaning friends, at first supportive, albeit coddling, before chastising Sean’s absenteeism as his implied isolation worsens. But who needs friends when you’ve got the tried-and-true method of self-medication in the 21st century: sex and booze and drugs and doomscrolling into numbness? Despite these heavy themes, May Mga Uod Ang Tak Mo never has that numb feeling. It’s always an open wound, a scab to be picked at in its raw edges.

At parts of the play, I wonder if I should be taking more note of the invisible parts of the work—lighting, sound, AV, set design, costume, or even KŌKIRI and the array of stunts that have the audience recoiling—before being swept up again by the strength of Sean’s writing and performance. A solo show to reinvigorate Tāmaki Makaurau’s strangled theatre scene, May Mga Uod Ang Tak Mo is a beastly machine, where all moving parts work together to be in service of the whole. All accidents feel intentional—a dry throat is a misdirect for a saxophone solo, a fit of laughter turns into a WWE-style showdown. The cues are tight, and the direction keeps the show at such a pace that, as an audience member, your mind is nowhere beyond where the makers of the story need you to be.

My nitpicks about the May Mga Uod Ang Tak Mo are minor and specific to me—I sat in a weird spot where I couldn’t see the AV super clearly, I think “yuck, don’t drink the urn!”, I hate a meta-textual reference to me being in the audience. But what is there really to say? The star is grieving, and the grief will last a lifetime! To be on Sean’s journey of grief—a work that has no concrete answers for how to deal with grief, filled with a feat of the hyperactive visuals and violence and musical interludes—it’s an incredibly generous thing to give. The play comes to as natural a close as a reset play can—with the clarity that the person you’ve disappointed and has disappointed you is proud of you and does love you. And it’s not enough to bring an end to the grief, because how could it end, but it’s enough closure to play your dad’s favourite song on the piano and go home.