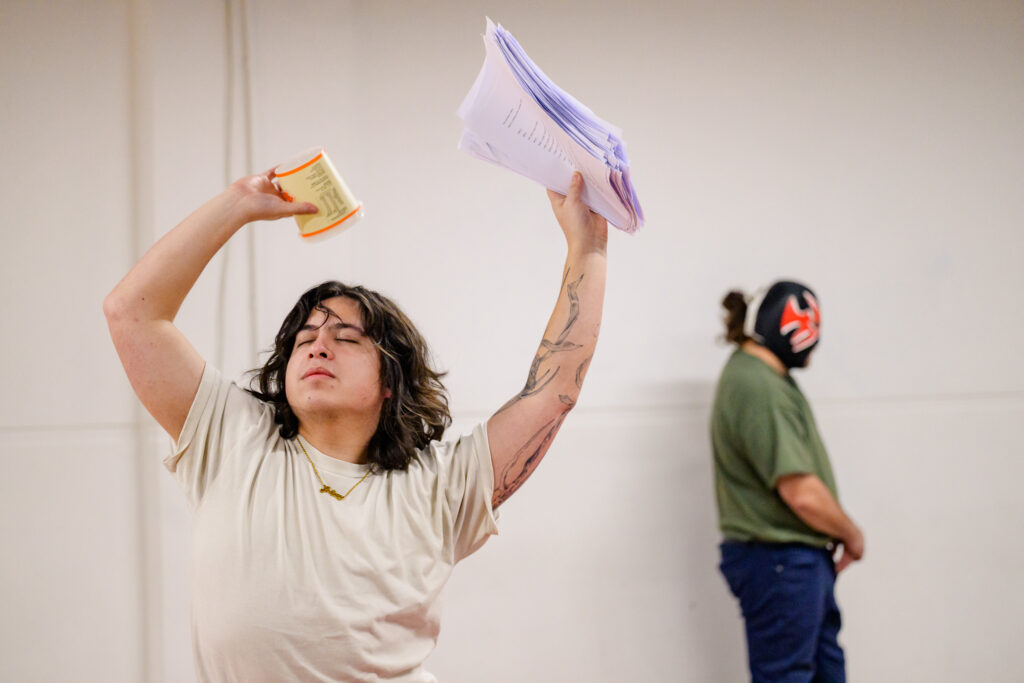

For those paying attention over the last few years, Sean Dioneda Rivera has been directing a large quantity of the solo theatre shows at the Basement Theatre (To Be Frank, Concerning The UFO Sighting Outside Mt Roskill, Auckland, SNART). Though formally trained as an actor, his practice has expanded to include directing, often as a way of supporting the work of his peers. Now it’s his turn to perform his ‘solo’ show, which he has been rehearsing over the last month or so.

The play, May Mga Uod Ang Utak Mo (translated to: There Are Worms In Your Brain), tackles grief through the repeating structure of the reset play. I spoke to Sean about the process of being back in the actor’s seat, as well as what has informed the writing of this play.

NJ: This is technically your third go at this play, is that correct? Or third iteration of the play?

SDR: It is the third iteration of the play. Retrospectively looking back at the other attempts at the play, all three of them are very, very different plays. They have different characters, different plots, different stories, but they’re all tackling the same themes: grief in the digital age and radicalisation of young men. So, I think this attempt at it, with a stronger idea of form, and how I want to fuck with and subvert form, is, at least for me, at this time, the form of the reset play and the solo, has meant that all the themes have been split wide open and I am able to explore them as much as I want to, while still adhering to the themes. Which is why this is the most successful iteration of exploring those themes.

NJ: And how did you arrive at the reset form?

SDR: I think it was due to working on Losing Face [Nathan Joe, 2023] as an assistant director, and then also working, reflecting on Another Mammal [Jo Randerson, 2021] as well, which are both reset plays I’ve been a part of.

NJ: Which is kinda crazy. The reset play is pretty niche, yet you’ve somehow, in this Aotearoa theatre ecology, been a part of two…

SDR: I’m an ecology of reset plays.

NJ: And now you’re delivering this third reset play into the cultural consciousness. Not to say there aren’t other ones, but those are three in a relatively short window of time in the scheme of your theatre history.

SDR: (jokingly) Losing Face and Another Mammal are the parents of this play.

NJ: Well, I’ve always wanted to raise a child with Jo Randerson.

SDR: But it was through working on those plays, and coming to understand what the reset form does for a theme. That form means that there is something the character is not getting right. That there is a right way to do things. In the context of grief, and especially in the context of white funerals, there is a set way these things are run. They will run this amount of time, and you do this thing now, and you say this thing now. I think grief, as a thing, is an impossible thing to get right. The rigidness of a funeral challenges or compresses that. The reset form meant there was a way to fuck with a funeral to its utmost degree. To throw every piece of tradition or every piece of respect out the window. That’s how I arrived there.

NJ: I really feel you’ve been so, so successful. Reading it a few nights ago, I feel very moved by the matching of subject matter and the form. Grief feels like the most fragmentary and non-linear emotion that we have, more than love in some ways, because it forces us to relive things. Grief does that to us. It asks us to relive moments, it asks us to not forget.

SDR: It forces you to not forget, it forces you to remember. Whether you like it or not.

NJ: You’ve directed a lot of solo shows in the last couple of years. How has this informed writing and performing in your ‘solo show’?

SDR: The beautiful thing about solos for creators and for writers is that it truly is a peek into the brain. No matter if this person is making a multi-character solo or they’re playing a whole different bunch of people or they’re playing Frankenstein’s monster, the show intrinsically, because it is just them on stage for an honour, it is about them to their fullest degree.

As a director, when I’m working with a solo performer, it’s about how do we excavate the stuff in the play, but also how do we excavate what is your superpower on stage.

So I think writing this and creating this has been an opportunity to do that—to do what I do to other actors to myself. What am I good at? What do I want to be really good at? What do I want an opportunity to do that I haven’t been able to do onstage? Scaffolding moments where I get to really stretch my craft, and just go fucking full send it.

NJ: Coming into the process, what did you think your superpower was?

SDR: I think my superpower is . . . Or, I thought my superpower was comedy and taking things up to 10 and then dialling them a bit too far for a bit too long. That’s what I saw as my superpower.

NJ: And now?

SDR: And now through the process of doing A Rich Man with [Sam] Brooks, which is a show that demanded me to cry for two hours, and then doing this show, which is funny for a bit but not really, is listening and rhythm. In Sam’s show, it’s a matter of listening to the music of that entire show. Inside of this show, it’s listening to how fast a tone or an emotion can switch. How fast things can be flipped on their head. And what I as a performer—and what I’ve done as writer—to scaffold that. So the audience never quite knows what’s coming next and is never comfortable inside this service.

NJ: That’s really beautiful and exciting. That you’ve gone through the journey of finding a superpower that you weren’t necessarily aware of prior to A Rich Man and prior to the rehearsal process of your show.

And how has it been with Nī [Dekkers-Reihana, director] and Tyler [Kokiri, stunt coordinator] as your other bodies in the room?

SDR: Really good. Because I’m so used to holding other actors when they’re doing their very personal works, it feels very liberating as an actor to be held inside of that. “This is my baby, be careful with it.” Even though the show is very heavy and gets very intense at times, the process of making this has never been heavy. It’s been incredibly light and fun and stupid because that’s just our nature as people. We’re all very stupid.

NJ: So, this is quite a personal play. How important is it for you that audiences understand this is coming from a personal place? Do you think it’s important for audiences to know?

SDR: I don’t think it’s super important. I think there’s enough scaffolding around the show. It is about me and my dad, and in real life. And that’s about as much context as you might need for this show. I think there’s lots of beautiful moments inside the show that will impact people I’m close with a lot more. But as a viewing experience, I think it’s completely unnecessary to know who I am or what my given circumstances as a person are.

NJ: And what’s it been like for you drawing from that place? Were there any difficult stages?

SDR: Nothing has been difficult so far, outside of normal show difficult things. Writing from that place of grief . . . I’m really used to seeing in the media that grief is this slow, melancholic emotion that you start drowning in or that you sit in. For me, writing from that place, I find grief is something that is really hot and activated. More than sadness, anger and confusion are the things that bubble to the surface when I’m recalling those times. I just wanted to reflect what grief is to me. I think that specificity will connect with a lot of different people. Because everybody grieves in their own incredibly unique and strange way.

NJ: What does the writing process look like for you?

SDR: The writing process for this play, because it delves with the internet a lot, was definitely not written in order. A lot of inspiration just comes from the scroll. The doom scroll. And just spending time with too many tabs open on the computer late at night, with different kinds of media blasting into my brain at once. Like Reddit, 4chan, YouTube videos, weird sites that are like YouTube but are not YouTube. Just places that you find yourself in the middle of the night. The places that your morbid curiosity takes you.

In terms of the bones of the play, the play is written as me reading the eulogy that my father, in real life, wrote. The eulogy is actually what he wrote. And I guess that is an important part that is a nice thing to know as an audience member—that the eulogy inside the play is the eulogy he wrote for himself. And the show is a deconstruction of that and a response to that, as well as this other fuckery. It really came down to me reading his eulogy and going, “Oh well, what do I think about him? What do I think about what he is saying here? How true is it? What has been changed for the sake of the people coming to the service? What is him saving face? What is him being brutally honest?”

NJ: Have you come to any answers in this process in how you feel towards it?

SDR: Things have definitely shifted. This always happens where I’ll read something that somebody else has written, or in this case write something, and on paper, I’m like, “Oh my god, that’s so fucked up.” And then you do it on the floor, or you hear it out loud, and it’s okay. Not even okay. It’s just real.

There are so many more layers and nuances to how I feel towards this situation than I even actually thought. Which is a really lovely feeling. A journey that the character Sean is going on, but that I’ve also gone through as well.

NJ: Like most theatre-makers, you’ve worn a lot of hats. Is that by choice or necessity?

SDR: I think it is by necessity. The industry does demand out of our creatives, especially in its current climate. But inside this process, I’ve really enjoyed taking a step back from being the creative lead. I am an actor. I am a performer. And assembling the team, that stuff was the last bit of creative direction that I did. It’s in Nī’s hands. So if the show sucks, it’s their fault. [laughs]

NJ: You’re not as responsible to the process.

SDR: So that’s been really lovely. I really enjoy writing, as much as it can be laborious and confusing and hard. As much as it is a thing that is born out of necessity, each of those things . . . each time I direct, I think it makes me better at acting, and every time I act, it makes me better at directing. And every time I write, it makes me better at dramaturgy, which you need for directing. All of it is a snake eating itself and getting better, or whatever that thing means.

NJ: Yeah, what’s up with that snake? Who taught it to do that?

I feel the same way. The necessity of it is a gift, but a pain, right? If it wasn’t a necessity, what one would you want to focus on, at this point—

SDR: —Directing.

NJ: Ohhhhh!!!

SDR: You’ve asked me this question before and given me the exact same reaction.

NJ: (laughs) Yeah, yeah, yeah, you wanna direct People, Places, Things, blah blah blah. Maybe in acting again you’ve . . .

SDR: Acting is probably on the bottom of the list.

NJ: Did you ever consider someone else performing in this version?

SDR: Not in this version. And in doing [Scenes from a] Climate Era [David Finnigan, 2024] last year, is when I was like, this person [Nī] is probably the perfect person to hold this show. In terms of best practice, connection as people, and as people with similar tastes, and also whakapapa of making process and lineage.

Halfway through this process, I was talking to Ben Wilson, who was one of the first people who was with me when I first started making/doing theatre. Ben Wilson and Keegan Bragg—their processes really informed how I work and navigate the theatre world. And finding out that Nī had directed a show that Ben had written when he was young, when he was a young pup, called Fred is Cold [2016]. That recontextualised things on why I am the way I am in theatre rehearsal rooms. [It] has come from here and looped back around to this person holding this process now.

NJ: Nothing’s an accident, right? Especially in an ecology this small. It’s not an accident, it’s a reset play, and you were on Another Mammal and Losing Face. It’s not an accident that you were informed by Ben and Keegan’s practice, and Nī was also part of that practice, and now is here. Everything has a whakapapa.

SDR: Which I thought was a beautiful . . . watershed moment.

NJ: How gorgeous.

May Mga Uod Ang Utak Mo (There are Worms in Your Brain) opens this Tuesday, 27 August, for three nights only at Basement Theatre and is presented by Punctum Productions.

Featured photos by Jinki Cambronero, courtesy of Punctum Productions.