There’s something about Frankenstein that’s just in the zeitgeist right now—Guillermo Del Toro is releasing a new adaptation at the end of 2025, Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things recently took the film world by storm, The Court Theatre recently programmed a production, and Free Theatre’s Frankenstein still stands out in my mind as the finest avant-garde production in Christchurch in living memory.

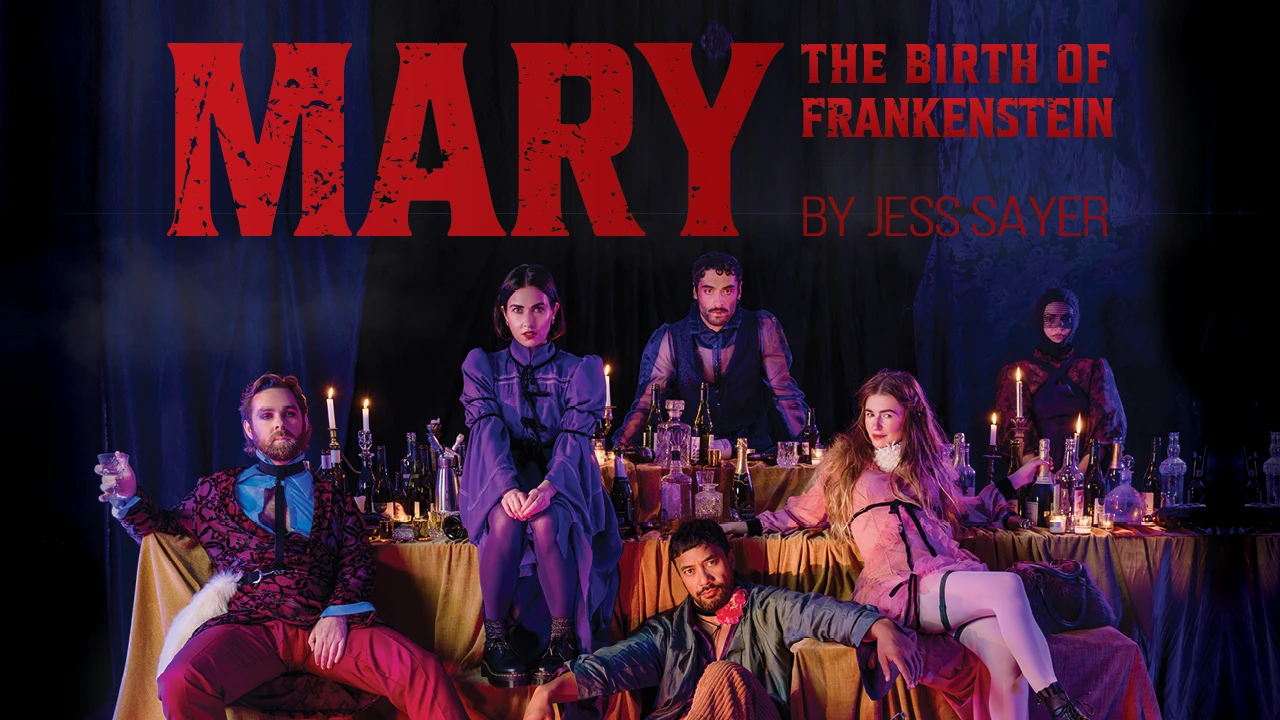

Now, in Auckland, Jess Sayer’s Mary: The Birth of Frankenstein takes as its starting point the real-life gathering of Mary Godwin, Lord Byron, John Polidori and others that generated Frankenstein. Sayer’s play takes place over one night as these characters explore artistic process, the cost of artistic creation, female rage, and murder. The play is dedicated to Mary Shelley, “with apologies,” serving as a clear signal: this play is not about historical accuracy. This play is about the full force of darkness, both literal and figurative, and everything that darkness can encompass, including lightness.

I arrive at the Auckland Theatre Company rehearsal rooms at the end of the second week of rehearsals. The cast, led by director Oliver Driver, has just completed a first full run of the play on its feet, and playwright Jess Sayer is stoked. As we sit down to discuss the process of the play’s writing, Sayer mentions that she “always gets nervous with these things,” referring to the discussion itself. A recurrent theme during our conversation is the vulnerability of writing and the implicit anxiety that comes with putting work out. The theme pops up both because this is a huge-scale project compared to previous plays Sayer has worked on, and because Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was written from a place of deep vulnerability and historical contingency. Sayer tells me that Shelley learned how to write her name from her mother’s gravestone, just one small insight into the relationship between Shelley, Frankenstein and death.

Mary: The Birth of Frankenstein took seven years to write. Sayer tells me that she stopped working on it multiple times over this period, unsure where the work was going or who it was for—or if it was even possible to stage. It was the play’s director, Oliver Driver, who encouraged Sayer to keep working on the script over this period. “We’re a great creative match,” Sayer tells me, with both encouraging each other to lean into their most provocative tendencies. “That’s the cool thing about Oli,” Sayer says: “he was always like . . . don’t worry about anything, don’t worry about how we’re gonna do it . . . just write it!” To Sayer’s surprise, the play was programmed by Auckland Theatre Company as part of their 2025 season following a successful playreading a year or two earlier. “Another cool thing about Oliver,” Sayer tells me, “is that he’s very interested in theatre being theatre, bringing in other art-forms and different artists to make elements of the play.”

One of these elements is lightning, an element of the play in which pathetic fallacy comes to the fore—weather reflects mood! The lightning also reflects the history of Frankenstein itself—Sayer points out that Mary Shelley’s book is never explicit about how, exactly, Victor Frankenstein’s creature is animated. It’s James Whale’s 1931 film that first utilises electricity and lightning as a visual representation of the creature’s animation. Sayer also points out that Shelley’s novel never refers to Victor Frankenstein’s creation as a ‘monster,’ instead referring to them as a ‘fiend’ or a ‘creature.’

It’s clear Sayer knows her stuff. Our conversation traverses big topics like climate change and the growing distrust of science, just as it traverses smaller anecdotes like the invention of the bicycle in 1816, the same year in which the play takes place and in which Frankenstein was written. Sayer points toward influences ranging from true crime podcasts as a sleep aid to entries in the theatrical canon like Edward Albee’s The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? or Caryl Churchill’s overall career.

“This isn’t just a fun night out at the theatre,” Sayer tells me. “It’s a horrifying, shocking play . . . but it’s also really fun and really entertaining.” The end of act one—no spoilers!—promises to be disturbing and surprising in equal measure, but Sayer quietly predicts it will generate some laughs. When I ask Sayer what she’s most excited for about the show, she is incredibly gracious: “I can’t wait for people to see how amazing [the cast] are,” she says.

Based on my conversation with Sayer, audiences in Auckland should also be excited to see Sayer’s sharp intellect, macabre sense of humour and depth of research brought to life in a play that promises to surprise, surprise, surprise.

Tickets to Mary: The Birth of Frankenstein can be purchased via the Auckland Theatre Company. The season runs from 21 August until 7 September at ASB Waterfront Theatre.