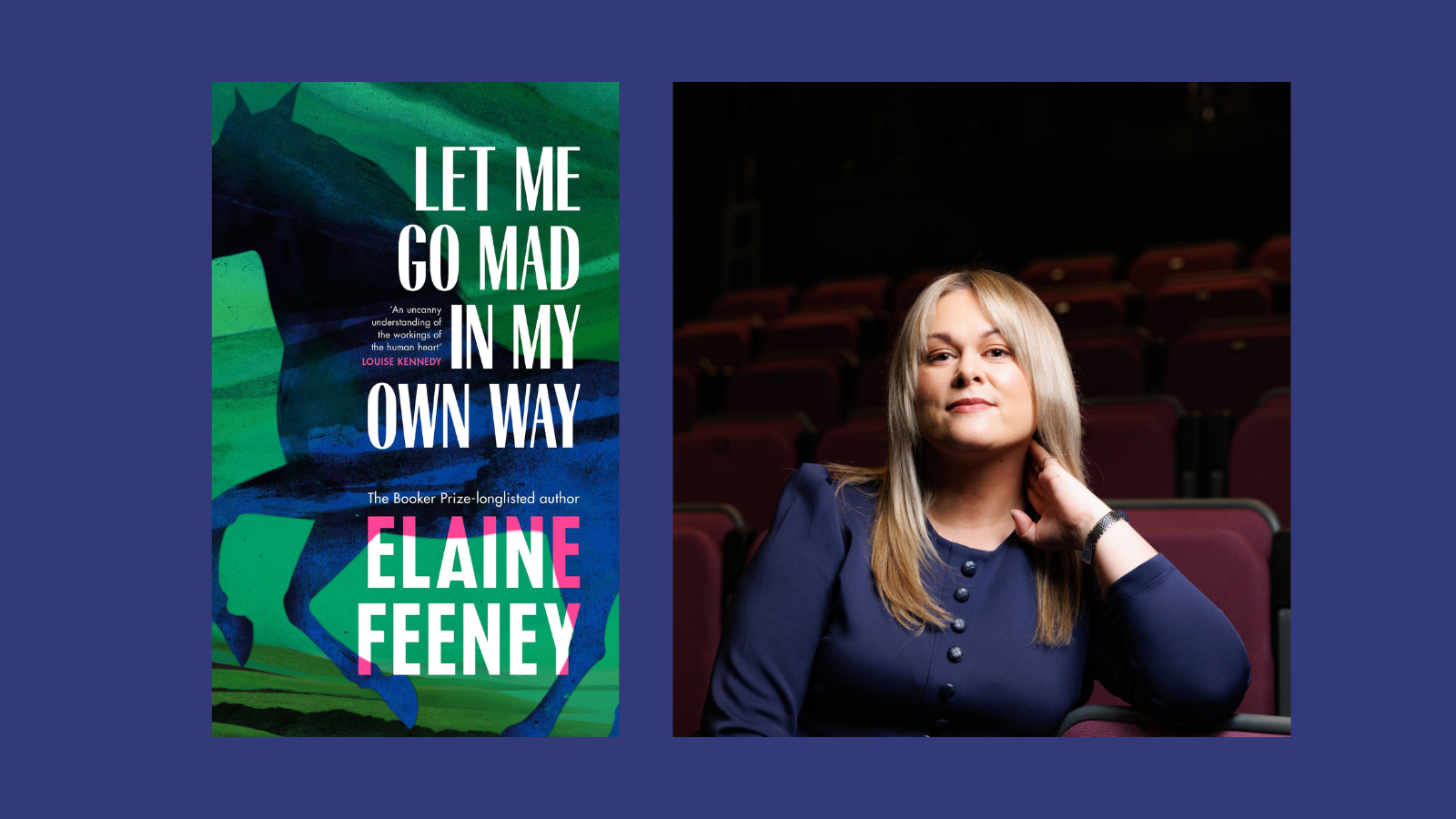

At Verb Readers and Writers Festival 2024, Aotearoa was introduced to the fantastic Irish novelist and poet Elaine Feeney. We are very lucky at bad apple to have built an enduring connection with Elaine, and when her new novel Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way was announced, we knew we had to set up an interview to hear about this stunning book.

Bridging the distance between Ireland and Aotearoa, Ash Davida Jane interviews Elaine through the marvel of the internet to provide us with this thoughtful, in-depth exploration of the novel.

Elaine Feeney is an acclaimed novelist and poet from the west of Ireland. Her debut novel, As You Were, was shortlisted for the Rathbones Folio Prize and the Irish Novel of the Year Award, and won the Kate O’Brien Award, the McKitterick Prize and the Dalkey Festival Emerging Writer Award. How to Build a Boat was also shortlisted for Irish Novel of the Year, longlisted for the Booker Prize, and was a New Yorker Best Book of the Year. Feeney has published the poetry collections Where’s Katie?, The Radio Was Gospel, Rise and All the Good Things You Deserve, and lectures at the University of Galway.

ADJ: In Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way, you oscillate between first-person narration from Claire’s perspective and third-person, limited mostly to knowing Claire’s internal thoughts, but not entirely. How did you come to this way of telling the story and why is it better than just using third person throughout?

EF: I don’t think there’s a single right way to tell a story—every narrative for me demands its own approach or voices. I’ve always been drawn to shifting points of view. Claire O’Connor, the novel’s protagonist, is a classic unreliable narrator, because like all of us, her worldview is limited, and often distorted by memory and emotion. That narrowness felt right for certain parts of the novel. But not for it all. That said, I really trusted Claire as a storyteller, and this unreliable narrator shifts in the last third of the book, when Claire recalls a violent incident from her childhood with a marked reliability.

As the story moves through time—especially back to the shadow of the 1920s and the Black and Tan violence in East Galway during the Irish War of Independence—I needed other voices. There’s a wild and untamed current of violent history flowing beneath Claire’s life, something fierce and haunting, and it couldn’t all be filtered through her alone, that would neither serve her well, or the history of the family.

This is a novel that I consider loosely to be the third in a trilogy of novels around buildings / Institutions. I’ve always been fascinated by rooms—what they hold, who’s in power in them, and what they remember. My first novel, As You Were, unfolded in a hospital because I spent a long time in a hospital and I kept wondering: who died in this bed? Who stood beside them? What fear is held in the walls, the mattress, the bed posts? My second novel, How to Build a Boat, was about an oppressive school and a free spirit who unsettles the order and rigidity of the building by making a boat inside of the walls and setting it free.

This novel is my third about institutions, and it’s about the home as an institution, houses, and what they hold on to. The old house beside Claire’s bungalow-the one she inherits after her father dies, is dense with memory and has been witness to a very violent reckoning by the Black and Tans on the O’Connor’s ancestors. It speaks to the stasis that the past causes, so the family have never knocked the house down. I needed the house to speak, and as an inanimate object, that can pose a difficulty! So I turned to Greek tragedy and to old Irish ballads, an oral form of story-telling, to the kind of sources that are left behind, bullet holes in walls, etchings, plaques, all handed down through generations, and the voice or form I created was a kind of naïve chorus—voices drawn from the house’s past, as though it could almost be sung. Or like a fairy-tale I would have heard as a child. That section has its own rhythm, and it’s very much shaped by the cadences of my grandparents’ way of speaking, and the older people I grew up around in the west of Ireland. Many of whom, and their ancestors, had been banned from speaking Gaeilge (Irish language) and had taken on English due to enforcement of the language, and so there was an odd rhythm and musicality that came with the way they inherited language. (Hiberno-English). So this section has its roots in orality, a rhythm that doesn’t often find its way into print, but it carries a kind of truth for me that was essential.

Claire’s story also moves across time. She returns to the 1990s, to the violence of her childhood. I write that part twice—once in third person, and then again in first. The second time, she’s telling the story to herself, and now, she’s actually claiming it. That shift was essential. It marks the point where she becomes reliable, or at least where she starts to own her unreliability. By the end, she’s the one telling the story. That was the only way it could happen—she had to get there herself.

ADJ: Claire is drawn to a particular tradwife influencer, Kelly, who posts vlogs and videos of her life. It leads Claire to a sort of fixation on homemaking and domestic order, but underneath the cooking of delicious, multi-course meals and mayonnaise hair treatments and meticulously planned table dressings, there’s a sinister feeling to it all. How can we resist the pull of this kind of order, and what it signifies?

EF: While writing, I found myself thinking constantly about how women around me live now—and how much of that is still shaped by the past. I’ve always been drawn to writing women who are stuck in some way, maybe caught between inherited burdens and uncertain freedoms, or maybe that’s personal to me. I thought a lot about my mother, and my grandmothers and their mothers when I was writing this. I moved in my life and opportunities, so far from their types of lives, and I often feel a guilt around that. Though I claim to rarely feel guilty, but of course, I do. I make my own money. I live independently. I have freedoms they couldn’t have imagined. But I also carry what they carried, and one of my biggest regrets in life is the unlived potential of these women.

In Ireland, women were fundamental in the foundation of the state. Cumann na mBan (League of Women) played a major role in the Easter Rising, and the aftermath. Yet women were institutionalised at staggering rates after the foundation of the state in 1922, well into the twentieth century. That history didn’t vanish from our lives, many families are affected by it (See Tuam Oral History Project at University of Galway). It affected my creativity—in fact, it seeped in.

The nuns who educated me when I was young seemed very angry, and though corporal punishment was banned in 1979, they still used it. As an adult, I encountered fierce misogyny working in an all-boys secondary school for decades. Violence was something that I was used to growing up, like many Irish people, I experienced it, and animals around me also experienced it. So maybe I am asking this novel, if perhaps that cruelty is a response to colonial trauma? A need to control women as a way to stabilise the new state that took hold? But of course, it is not an Irish phenomenon, it is universal, but I go small, into the local in my writing. To that end, I can only stay with the story I’m telling, and that can’t answer it. I don’t have any answers to how violence begets violence. Fear definitely plays a part in people’s ability to ‘other’ one another and met out savage punishments. But I stay local in this novel, as Patrick Kavanagh, the Irish poet, once wrote, “Gods make their own importance,” I guess. Was this violence a response to fear, to independence, or a warped sense of morality? Whatever the reason, it created a brutal legacy for some decades, particularly for women and for their children. Of course, everyone suffers under these regimes. My husband attended an all-boys secondary school as a boarder in the 90s, and he remembers a lot of violent punishment too.

Feminism, too, has evolved. When I was a young feminist in university in the late 90s and early 2000s there was a different kind of urgency, particularly around abortion rights. Lately, I’ve spoken with younger women—bright, articulate women—who are planning elaborate hen parties and baby showers, changing their names, creating pristinely curated domestic lives. Many of them are softly following tradwife influencers online. At first, I was irritated. Then I felt sad, but mostly, I felt out of touch, or that it was none of my business, it was about choice, right? But then I felt that it is just another manipulation of the right, and this rise of ‘traditional roles,’ and the silencing of people claiming their power from areas of intersectional and state-structured marginalisation. People who fought hard to be ‘in the room’ to have fair freedoms, to exist in peace, equity, education, are being discredited as ‘woke’. Of course, this is just people speaking truth to power, and power doing what it always likes to do—ridicule what makes it afraid.

But the tradwife movement, well, this movement ultimately feels like a retreat—not just from feminism, but from life’s messiness, the raw, unstageable parts. I understand the pull, but it’s warping our sense of what it means to live a messy life. I doom scroll like everyone else—moving from a video of sourdough starter to footage from the horrors in Gaza, where innocent people are live-streaming their own genocide and annihilation, and scrolling onto the waves of news about the rise of global fascism. The psychological whiplash is immense, the world seems fucked and I feel powerless. And so writing a novel in the face of all that? It felt like a privilege and that I had to bring something to the page. Sometimes I think with our freedoms, making art is exactly what we can do, or rather all we can do. And maybe booksellers and publishers are hand-selling the small revolutions.

Ultimately, Claire’s obsession with domestic perfection made sense to me. She’s trying to hold her world together. Cooking, cleaning, colour-coding—it’s not just about homemaking, it’s about survival. If she lets the past in, it could destroy her, so she desperately clings to control. And of course, all that control sets the stage for collapse at the dinner party at the end of the novel—equal parts polished and deranged—is the inevitable unravelling. That tension, between the surface and what’s beneath, is threaded through, between a clash of classes and people and the past arriving, a century on, at the kitchen table.

ADJ: I keep coming back to the title because this idea of ‘madness’ is so central to the whole book, and particularly the ways in which some forms of madness are more socially acceptable than others. The madness of women always seems to be viewed as worse somehow than the madness of men, even when men’s manifests as violence against others. At what point in the process did you find the title, and could you tell us about how you knew it was right?

EF: The title comes from Sophocles’ Electra, specifically Anne Carson’s translation. When I read the line—Let me go mad in my own way—it clicked and made sense personally, and it made sense for the O’Connor’s, so it made sense for the book.

So many women have been labelled mad throughout history. And often, mad is a word used to police difference—to dismiss truth-tellers, to pathologise resistance. Growing up, I saw women silenced by that word. If you didn’t defer, if you spoke too loudly, if you went outside the lines—you were “astray in the head,” “hysterical.” “trouble” “women’s libber”, or the latest I read a lot is “unapologetic feminist.” The idiocy of that phrase. That language was a control mechanism. It still is, it’s constantly being used against people.

And of course, women went mad. Lock them away in institutions. In kitchens. Take their babies. Deny their pain. No financial autonomy. No agency. What else would happen?

Claire is shaped by that legacy; her father controlled her, and maybe he, in turn, was haunted by the story that defined his life. And his father before him—another man shaped by violence. I live in the west of Ireland, and the idea of ‘going west’—‘going mad’—feels very real to me. When the Englishman follows Claire home, and sees her world for the first time, there’s nowhere further west to go for this family.

ADJ: The majority of Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way is set in Athenry, where you grew up and still live now. What was it like to write a character with such a conflicted relationship with her home, being both drawn to and repelled by it, when this place is your home too?

EF: Athenry is layered with history. The Normans settled (unsettled it). Cromwell came here. Edward Carson, the unionist leader who denied Ireland Home Rule, his mother was born in the big house at Castle Ellen, just across the fields where I grew up. I’m not always comfortable here, though I’ve stayed. Maybe because it’s where I feel closest to my dead—some I knew, some I didn’t, and for this reason, there’s an inherent sorrow in the land, but there’s also creative fuel. And the town has changed, it’s more diverse now, and more alive, and this gives me hope.

But I did want to lay some ghosts to rest in writing this book, though I think I’ve just set them dancing.

ADJ: Woven in between the modern-day chapters is a narrative thread set in 1920, exactly a century earlier. It’s just three chapters, but everything else that happens, every bit of nuance in the relationships between the characters and what happens within Claire’s family stems, in some way, from those three chapters. With how significant it is, what was your thinking behind the structure of the novel and when we see different parts of that story?

EF: I studied history in school and university, but the oral histories I heard growing up often contradicted what was taught. That tension fascinated me and writing and fiction became a way to find a different kind of truth. I think the greatest truths now are in fiction—the irony of that.

I also wondered, growing up here, why did farmers cling so fiercely to small, often failing plots of land? Why did it matter so much to them? There was work in the cities, and why cling on to the hardship even when it didn’t make sense economically? But I realised in writing this novel that there was a kind of respectability attached to land gained after Ireland’s independence, like it was proof of post-colonial survival. But that weight passed down through generations. It was fear, too. You had to make it work, or you risked losing everything, so morals became entwined in an upward mobility as so often happens in the first generation of a lower middle class, and the morals of your family, and in particular, your wives and daughters, were under scrutiny.

The presence of the Black and Tans in the 1920s, coming into kitchens and the small homes around where I now live, shaped the kitchen I write about in the novel. The kitchen as political space—who sits where, who speaks, who listens, who is in charge. The mood of it. The love, the hardship, the siblings. And the old cottages where my grandfather and father were born are still standing near my house—they seem to be telling their own stories outside of the agreed narratives of history. The violence, the hunger, the love. We/they tried to restart a young country from those kitchens.

ADJ: What do you think it is about these colonial truths being represented in fiction that people might find challenging?

EF: Because it implicates us, fiction has a way of slipping past our defences, and when we recognise ourselves—or our complicity—it can feel uncomfortable, and perhaps it should. In two generations, my family went from a subsistence agrarian poverty to middle-class stability. My grandmother told me of the time the cow died and she thought they would lose everything, but her brother sent money home from the building sites in London, and that saved the fortune of the family. I have freedom thanks to feminism, and to women who broke ceilings and thanks to a welfare system that supported a free education, but I carry guilt with that privilege and like Claire, I’m still not sure what to do with it.

Ireland’s story is one of survival and violence, yes—but also of silences. Of what we did to each other. The English did monstrous things here, but the Irish did things to the Irish, too. Now we are embracing a multi-cultural rural Ireland, and change is everywhere. But what has been the effect of post-colonial violence, did it feed directly into other forms of violence? Into silences? The novel asks this question, but I fall short in answering it. Of course, I think this book is challenging, but I think books should challenge.

ADJ: Though it has its own singular voice, Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way feels like part of a conversation that has been going on for centuries. Are there specific works or writers you were looking to when you were writing this novel?

EF: I thought, for a long time, that I might write a memoir. But I don’t trust my memory enough and so I returned to fiction. I wanted Claire’s voice to be contemporary and sharp. The 1920s sections to feel like a ballad or a Greek chorus and the 1990s told in a more linear, controlled third person, perhaps maybe even, a kind of traditional novel (whatever that is, linear, chronological). Some readers have said the 1990s chapters are the best written, which I think just means they conform to the dominant style of approved fiction. There is a stylistic reason the different parts are tonally unequal—the 1920, well, many here were illiterate. The ballad structure borrows from the orality of that generation—how they spoke, how they told stories to survive. I read somewhere that if Joyce was writing dialogue in 1920s Dublin, why was this section of my book anachronistic! A crude google search might bring up the socio-economic disparity between the two places, the linguistic tapestry of the west of Ireland—the language (and people) lost due to the Great Famine of 1840s, the geo-political, social and educational differences of those who inhabited the pages of Ulysses and those in small stone cottages of East Galway at the beginning of the twentieth century who told their story aloud, and rarely if ever wrote them down.

In writing, I was influenced by Erasure by Percival Everett, especially the way it contains a novella within a novel. China Room by Sunjeev Sahota, for its dual timeline. Edna O’Brien is always in my head when I write. And Maeve Binchy’s Echoes—a big novel in a small town and women’s struggles.

I thought about The Seagull and Uncle Vanya for the dinner party, from Russia to Galway. I’m always haunted by Tom Murphy’s brutal realism of the west, John McGahern’s men, and Brian Friel’s wit. And Sophocles, of course. Shakespeare, too—the soliloquies, stories told straight to the audience.

If this interview has you wanting more, you can enjoy a short reading of Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way below. And for New Zealand readers looking to get their hands on a copy of this brilliant novel, you can order a copy online from Unity Books Wellington or visit the store in person!