In February 2020, right before the timeline shifted and the world was irrevocably changed by COVID-19, I went to a writing wānanga at Tūkorehe Marae. State Highway 1 stretched out from Pōneke towards Porirua, then Paekākāriki, Waikanae, Ōtaki and past that again towards Kuku. The marae car park where we all gathered was just off the busy road. At the time, I had been writing for a number of years, but hadn’t yet found my entrance into the literary scene in Aotearoa. I had just completed CREW257—a Māori and Pasifika undergrad writing paper—on the tail-end of my degree at Te Herenga Waka University. This kaupapa was a turning point for me in my mahi as a writer.

The wānanga was coordinated by two of our greatest writing aunties in the Māori literary world. Nadine Hura and Anahera Gildea. It was at this wānanga that I would meet and hang out with some of my absolute fave writers. The work of that weekend eventually led to the production of the pukapuka, Te Whē ki Tūkorehe, and the publishing of my first ever short story, Moumou.

I lead with this context because whakapapa is important. And that wānanga was a more recent layer in a far longer whakapapa of Māori writing. And because really I got to know Nadine Hura (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi, Pākehā) in the context of community-building, and the context of her wanting to challenge colonial literary norms. How do we create a book? Who gets to be in that book? Does a story even need to be a bound-paper book at all, and not a wānanga, or a textile, or a whakairo at the marae?

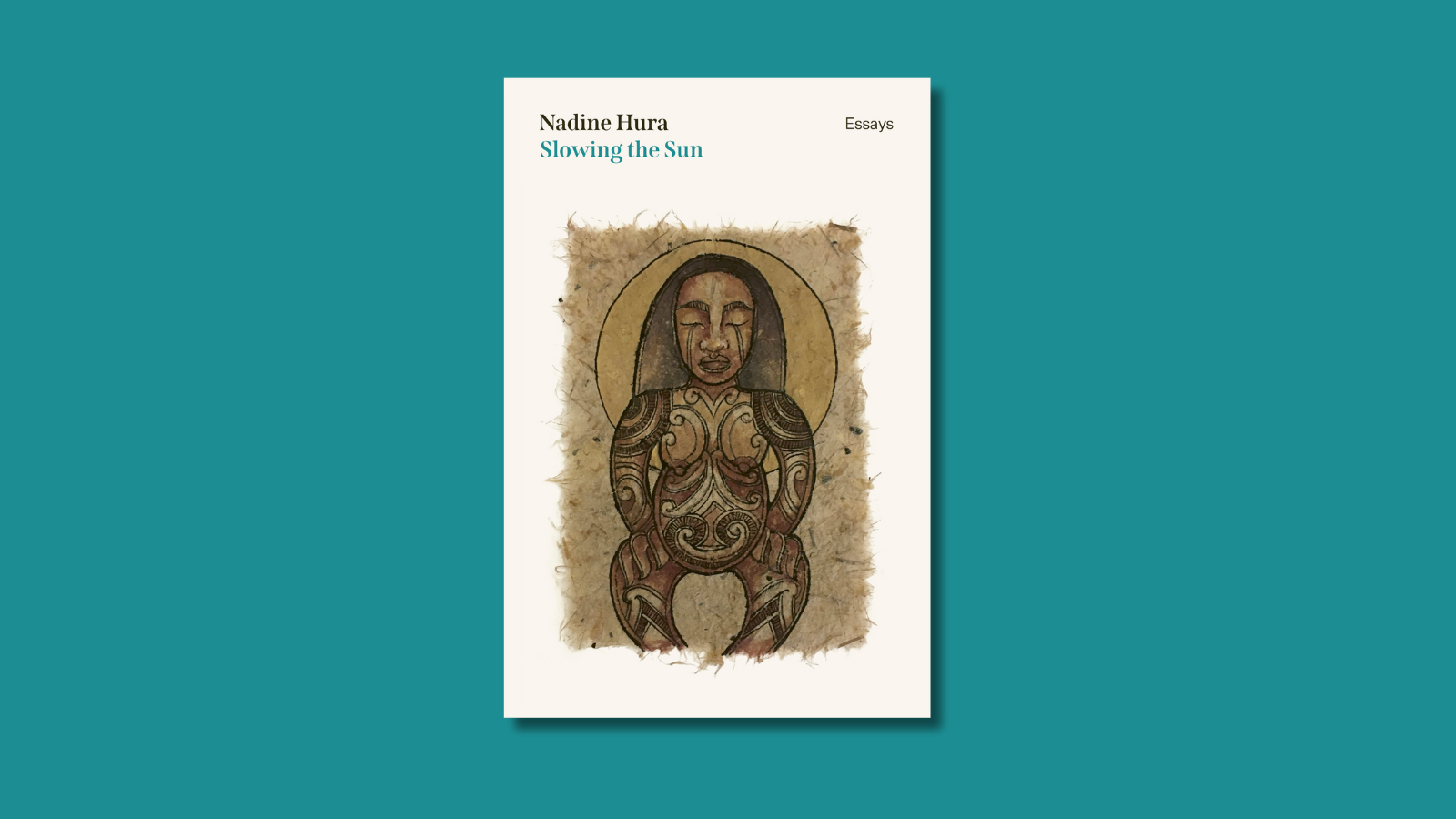

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I beheld Slowing the Sun, Hura’s new collection of essays. The bread and butter of Bridget Williams Books (BWB) is academically flavoured non-fiction. Those pocket rocket mini-collections like Lana Lopesi’s False Divides (my personal fave), the jam-packed collective pukapuka Imagining Decolonisation, Jade Kake’s Rebuilding the Kāinga. I knew there must be something like that in Slowing the Sun. But like I said, Hura is one of many contemporary Māori writers who are challenging the colonially-defined parameters of how and what we write. They do that in their yarn-anga’s (yarns and wānanga, I just made that up, ok), in their writing praxis and in the bodies of work that enter the world at the end of a million cups of tea.

Slowing the Sun is a pukapuka that is generous. It is a love letter for Hura’s whānau and wider te ao Māori, but it is also graceful in the way it invites non-Māori to sit in on what are sometimes incredibly personal conversations.

Hura weaves together several thematic threads. First are the stories of climate change in Aotearoa that are more journalistic and academic in tone (think methane, greenhouse gases, and all the bonkers acronyms of the international climate discussion forums). These stories are important, but sometimes hard to access elsewhere, or hard to engage with because they feel disconnected from the reality of daily life. Or just too overwhelming to make space for. But Hura’s climate stories are personal, humble in tone, and inquisitive. Characters like Hank Dunn (Te Uri o Tai, Te Rarawa) offer connection points in Hura’s accounts of sea-level rise, adaptation, and science forums drier than a Nature Valley muesli bar.

The next thread, most compelling to me, was the stories Hura shared about her whānau. In particular, her pāpā, and her brother Darren make appearances throughout the book. Her pāpā is a lot like my pāpā, a blue-collar Māori man who spent his whole life putting his body to hard work for his whānau and who was beaten for speaking his reo. Hura’s pāpā spent decades shifting rock and paving the roads that we all drive on today. Her brother Darren reminds me of many other men in my whānau, a brown man who was let down by systems colonial in design. When Hura writes about her brother, I hear the echoes of a grief that starts with the loss of a loved family member, but reverberates to a far deeper place of grief, anger, and a fire ignited by countless generations of colonial violence.

The final thread is woven in between these stories—a series of poetic vignettes focused on Māui and his whānau. They are a re-interpreting of pūrākau that lend a sense of wairua to underpin all of Nadine’s contemporary stories.

There are dozens of theories about why Māui turned my husband into a dog. Lol. I expect there’ll be more before the world is done. Let them wonder. All I’ll say is that grief lights up the whole sky.

As a writer myself, I was drawn to Hura’s knack for imagery. This beautifully threaded line of words from the chapter ‘Kōrero Pono’: Millions of jagged teeth have swallowed Raukūmara’s morning-song. Then there’s the way she portrays her pāpā’s work excavating the mystical / mineral-rich isthmuses of Tāmaki Makaurau. Or the way she blends the end of her marriage and the discovery of new love with her journey towards reclaiming te reo Māori.

I think the true triumph of this work is the way it connects big, often obscure and disconnective words like ‘colonisation’ and ‘climate change’, with the real, complex and textured ways that those things impact upon an actual whānau. That is such a gift to those of us who are really trying to understand and explain why things like the Regulatory Standards Bill, or the Paris Agreement, or Te Tiriti o Waitangi have a whakapapa that can touch our lives intimately.

People take their own lives in solitude, in much the same way as glaciers retreat and ice caps melt—most of the time we are not close enough to bear witness. But just because it is beyond climate science to show precisely how these disparate events are connected does not mean that they are not.

It is Hura who unearths those connections and examines them like a worm unexpected on wet pavement. Ko ia kei a koe e Whaea!