in a former life, in another time / a fox girl departs from the land of jade…

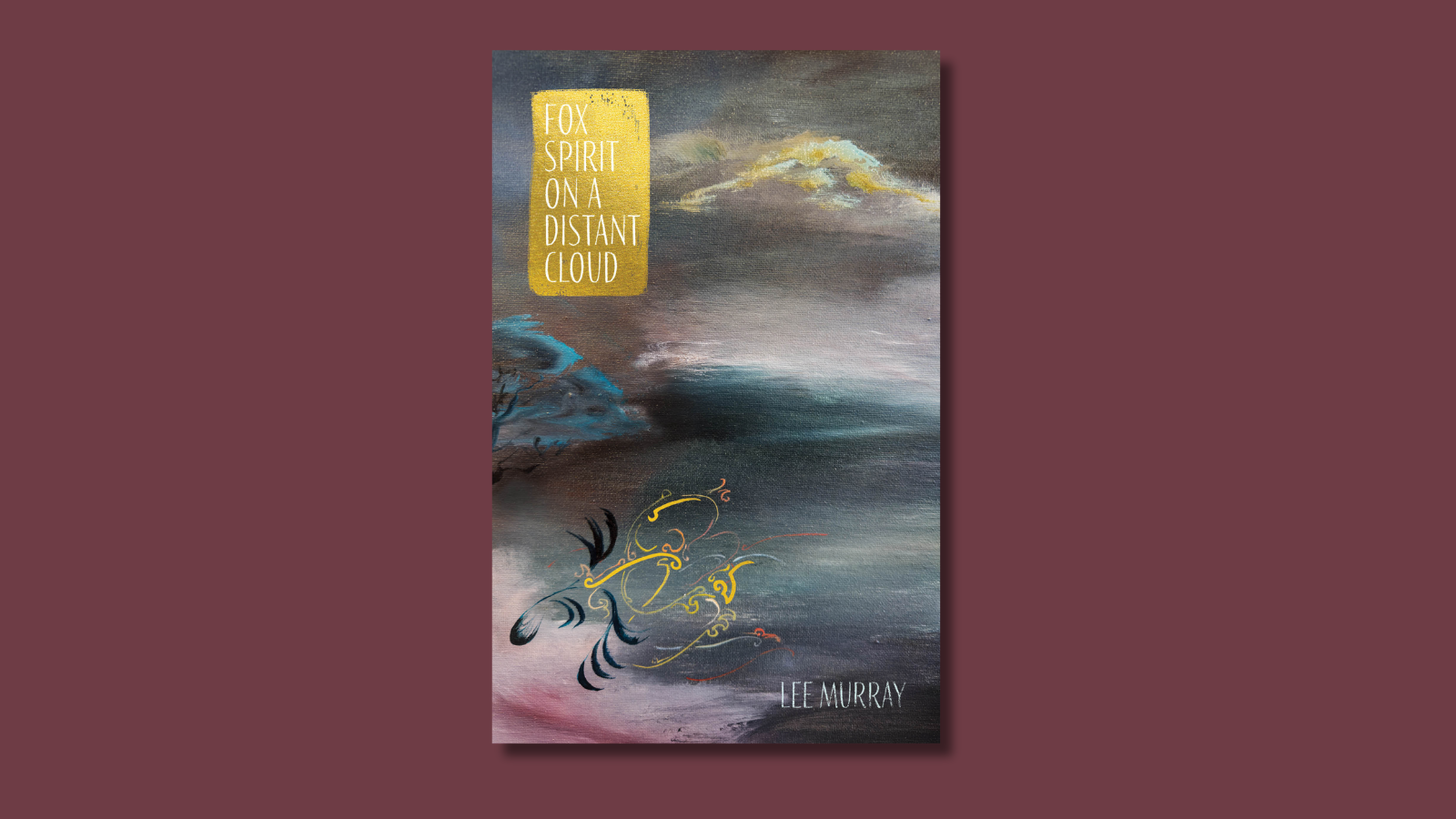

So begins Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud, a prose-poetry hybrid work from Lee Murray that depicts the lives and deaths of nine Chinese women and girls of the New Zealand diaspora. The collection is based on archival snippets of real-life historical figures and poses an interesting question about how we should interpret marginalised people of the past, who often appear in sparse detail.

Like other Chinese women in Aotearoa today, these figures offer me a cultural heritage to draw on, so I was excited for Murray’s interpretation. As historical figures, they often appear as little more than tragic footnotes in newspapers, meant to be interpreted as objects of pity. Yet, surely, these women experienced their own small victories, rich thoughts, and moments of pleasure. I wanted to see how Murray would expand their inner worlds, offering us a new perspective on these women who, despite their circumstances, braved the long voyage to new gold mountain, and carried with them their own determinations, hopes and dreams.

by the lake / a glint of a taonga

In her author’s note, Murray says she hoped to explore “unspoken things” in Chinese women’s history: “tales of mental illness and grief, poverty and hardship, loss and loneliness”. She certainly achieves this, laying bare harrowing tales of shame, anguish and isolation.

In this collection, Lee’s strength as a horror writer shines. Her haunting descriptions of New Zealand’s misty scenery and her skillful use of onomatopoeia combine to lend a distinct atmosphere to the work.

Throughout, Murray plays with compound words, mirroring the Chinese language structure of two-syllable words. In English, the words combine to make new meaning, one which occupies the hyphen between. It’s a motif that lends itself to the distinctly lyrical and sometimes playful quality of Fox Spirit. My favourites include “paddle-panic”, “chip-chop” and “ghost-mist”.

These compound phrases and the wider prose-poetry hybrid form embody an in-betweenness that haunts the central figures of the book. Chief of these is a 狐狸精 (húlíjīng)—a fox spirit from Chinese mythology—striving for immortality by wearing each skull and experiencing human life. Morally ambiguous, the fox spirit is employed to “bear witness” to these stories. Yet the fox spirit is not just a passive observer, it’s an active participant in the lives of Murray’s heroines. She appears in the rare moments when narrators defy expectations, break boundaries, and dare to have their own dreams. These are the most compelling moments.

In the fruit shop, we see our first protagonist build “a temple to the apple gods, a giant golden pyramid”. Later, she skips after her younger brother “keeping time with the clink-clunking, [sic] hard school shoes scuff-scuffing on the concrete.” It’s a fragment of a rich inner life: a musical rhythm and creative impulse that runs through the protagonist’s world. But it’s one that is ultimately snuffed out by the hard realities of being a Chinese woman in a time unfriendly to both immigrants and women.

But your heart still brims with silver.

It’s an ending characteristic of Murray’s heroines, yet one that doesn’t sit quite right. Although these women’s lives were marked by tragedy and often ended too soon, I couldn’t help but wonder if focusing on the macabre to the exclusion of all else risked pigeonholing these figures, unwittingly recreating the stereotypes and prejudice they were subject to in life.

Although it’s a narrative necessity due to the framing device, each story zooms in with graphic details of the women’s violent deaths. It has the effect of defining each woman by her end. It leaves me wondering whether there isn’t an alternate way to render these women—not shying away from the bitterness and horror of their realities, yet refusing to let it wholly define them.

The many protagonists in Murray’s stories are almost always framed in deficit, filled with unbearable longing for an overtly idealised, orientalist “motherland”. The language with which Murray ascribes their internal thoughts entrenches these women in victimhood. I can’t help but wonder if the real people who inspired these stories would want their stories told this way.

Since you are an ugly Chinese girl, a monstrous half-caste hybrid with a red welt scarring your throat, nobody wants you, not even your parents, who have been discharged of any responsibility.

One narrator is “woman-sick and an unexpectant burden”. Another is “just another Asian sex worker. Another hungry ghost.” Their lives are “tiresome, tedious”. The women often lack interiority beyond anger, disdain and shame. In story after story, the reader is confronted with the tragedy and insignificance of being a Chinese woman in Aotearoa.

echoes / howling / on the wind

Murray admits that her use of the fox spirit fails to give her protagonists a sense of agency. She says: “here in Aotearoa the fox spirit is as impotent as the women whose form she inhabits and subject to the same isolation, prejudice and cultural demands. Unable to access New Zealand society through culture, language and relational barriers, even a magical creature becomes a lonely spectator of life.”

It’s in this sentiment that Murray’s work experiences a failure of the imagination. Isolation, prejudice and cultural demands are challenges faced by women in all eras, and yet many still live rich inner lives imbued with their own meaning. Indeed, even within Murray’s tales, there are glimpses of it. In “frangipani wishes,” the protagonist doggedly visits the matchmaker, arriving in New Zealand with a stranger for a husband in the hope of a better life for her daughter. In “母 | mother”, the fox spirit pulls our narrator from the brink of death to give testimony. But these glimpses are few and far between, and even in these tales, despair and vengeance drive our narrators.

In most stories, our heroines simply succumb to their circumstances. In these cases, Murray fails to ask how someone might have built a life in spite of culture, language and relational barriers—even if that life is internal, even if it is isolated, even if it draws on a culture they are displaced from. Might these women have been driven by a sense of familial duty? Could they have been eager for a fresh start, for a new life, for a clean slate? There are so many possibilities for these women that aren’t depicted. It’s Murray herself who relegates her heroines to be “lonely spectator[s] of life”.

And, for an instant, you become your true self.

At the end of ‘婦 woman’, Murray notes the material she draws on: a snippet of the West Coast Times from 1881 which reports on a “real Chinawoman in Wellington… described as ‘an almond-eyed difficulty’.”

It’s a passage that reveals the central failure of the work. Murray seems to internalise some of the flawed rhetoric of her primary sources. In doing so, she repeats the existing narrative of the poor, helpless, doomed immigrant woman rather than interrogating it. In ‘婦 woman’, the narrator, despite speaking no English, embodies the newspaper clipping by describing herself as “an almond-eyed difficulty”.

congee / left in the pot / hardens

Ultimately, it’s a fallacy to expect an accurate portrayal of these women. Many left no trace of their own interiority, no letters or diaries. Many of them couldn’t. There’s no way to know what these women dreamed of, what led them to make their choices, whether bold, brave, or tragic. That’s the role of historical fiction: to fill these gaps with our own dreams, our own conceptions of our cultural heritage, our own ideas of those who came before.

It begs the question: why can’t we imagine more?