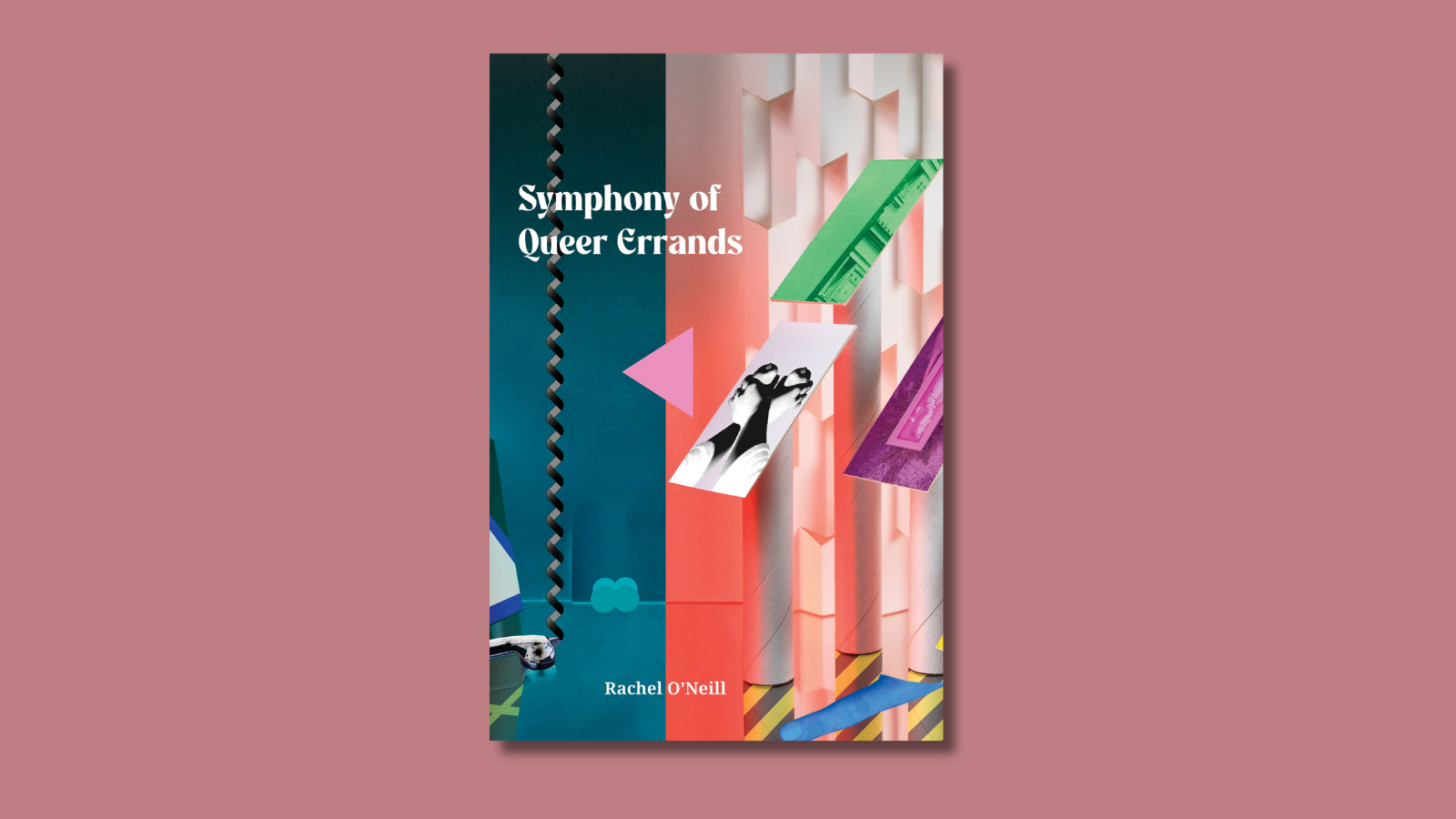

Symphony of Queer Errands by Rachel O’Neill (Tender Press, 2025) is more of an experience than a poetry book. This makes sense, given that the collection’s momentum builds towards the completion of a titular ‘symphony’, causing readers to be swept along with the surreal composition. Forgive me, but I have been watching Twin Peaks recently and I couldn’t help but hear Agent Cooper’s words in my head as I read this book: ‘I have no idea where this will lead . . . but I have a definite feeling it will be a place both wonderful and strange’ (Season 2 Episode 18).

Despite leaning into surrealism, the collection has a clear structure to anchor it, with seven parts building towards the eventual symphony in part eight. Opening sections include ‘Meet the Composers’ and

‘(Some of) L’Orchestra’, where fantastical characters and instruments are introduced. Next comes the workshopping, composing, and rehearsing. The final section reaches the natural climax of the symphony itself, which you begin to anticipate as you read. The collection is not set out like most in its genre, nor is its focus as diverse. It is unified by its theme and goal; producing the symphony. As the rear cover blurb describes it, this text feels a lot like a ‘concept album’. But this is no Pink Floyd’s The Wall. It’s so much gayer.

The collection has a multidisciplinary artistic emphasis, and not only due to its overt musical references. It is visually striking and makes deliberate use of space on the page, depending on the piece. Instrument introductions are prose poems; ‘The Score’ is more empty space and punctuation than words and the symphony itself uses a combination of layouts to achieve varied pace and evocation. In this way, the collection relies less on the careful wording of each line/stanza and instead uses a range of different artistic effects to create resonance. Perhaps this reflects O’Neill’s background as not solely a poet, but also an artist in other mediums.

There are two named characters we follow through most of the collection. The main character, from whose first-person perspective we sometimes read, is called ‘Ror-e-i-a’ with ‘so many vowels’ (p. 22). When the other central character, ‘Found Sound’, first introduces themselves, they make ‘Ror-e-i-a’ drop and do ten press-ups before revealing their name (p. 22). Their relationship continues in a teasing, warm, and fiercely creative manner. They correspond via dialogue and writing throughout and seem to be driving the production of the Symphony—and having a damn good time.

Humour, with a particularly fantastical bent, is another factor that infuses the collection. This is perhaps best illustrated by the ‘(Some of) L’Orchestra’ section, which consists of 16 prose poems, each titled for a different instrument, introducing them. My favourite is the ‘Anti-Gaslighting Bowls’ which produce stickers that can be attached to ‘gaslighting artworks, and even abusive makers’ and inject the recipient with ‘an inky request to get to therapy’ (p. 29).

Other honourable mentions go to ‘Z Chipped Stone’, ‘A Lost Whistler’, and ‘The 9,000 Foot Twit’, the latter of which emits smoke and steam, and takes ‘whole minutes’ after it has been played for sound to emerge (p. 30). This sort of humour, not entirely plausible, but echoing reality, is present throughout.

The comedy of the work is often contrasted by moments of groundedness. This occurs when elements of the current context bleed into the strange world being brought to life, mainly towards the end of the book. This goes all the way from the mundane, such as ‘Ror-e-i-a’ mentioning a ‘SPAM folder’ (p. 75), to key points in Aoteroa’s political discourse: ‘Here, on stolen land—’ (p. 92). The latter comes from a piece within the symphony itself titled ‘The chord of opening eyes and lips’, and declares, among other things, ‘I am a collusion—the colonial roots of dysfunction—a seed of my culture—my roots in violence’ (p. 92). A critique of colonialism seldom passes me by unapproved, so I appreciate that the collection still ties itself to our reality and history, though I wonder if its focus in this moment makes the perspective of the symphony too Pākehā-ancestry specific, and thus less absorbing for some readers.

However, overall the passage of time in the collection is confusingly expansive, fluid, and yet somehow unnoticeable, and by the end of the book, the symphony has encompassed everything and become a force unto itself. It feels like everything prior has been leading up to this point. The characters and the instruments dissolve to perform their function, and as a reader, you sort of dissolve too. In this sense, the symphony mimics experiencing joy—to be swept up, and lose sense of time, place, self. In joy there is only the present moment; in queer joy, there is only the symphony.