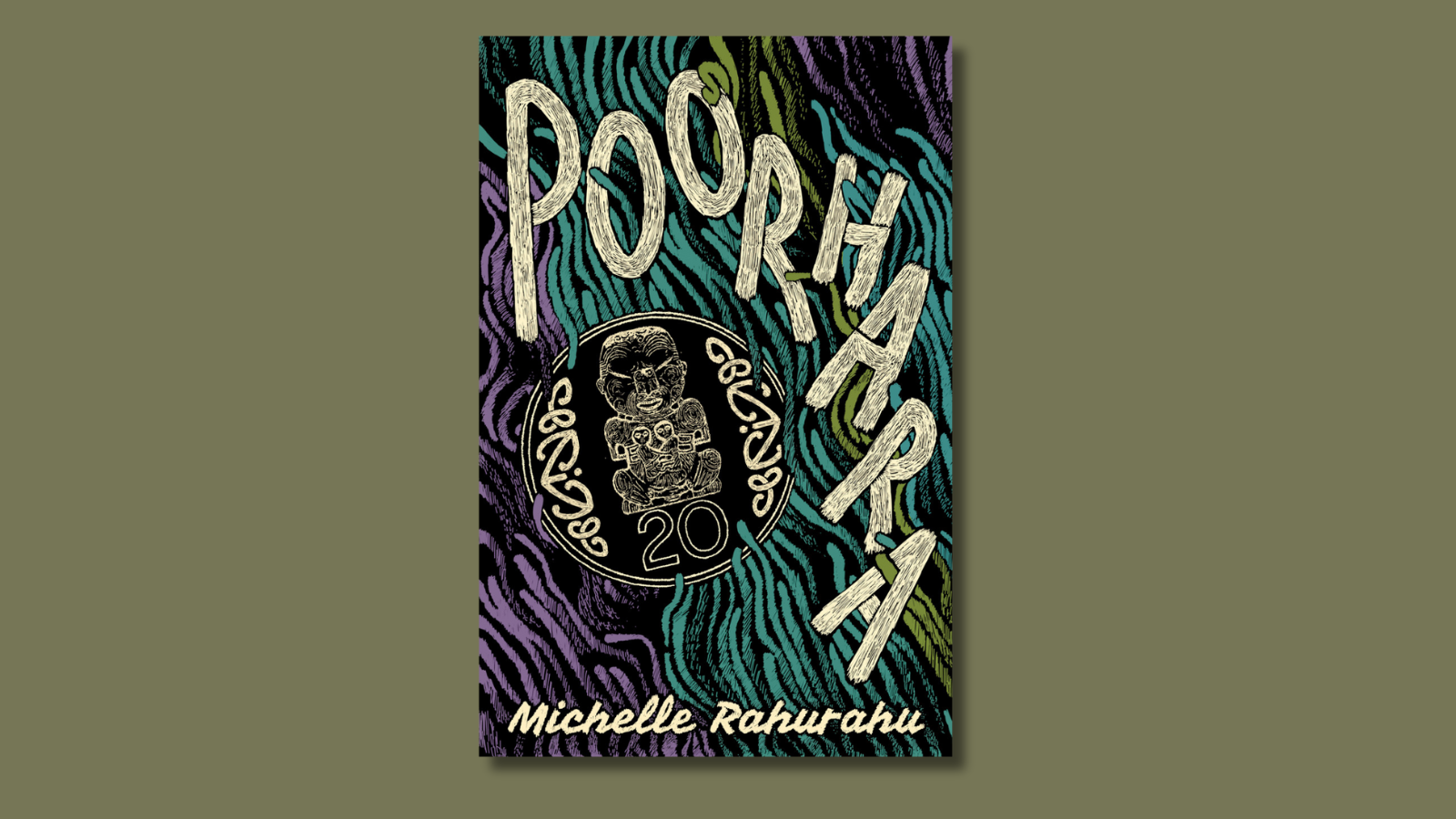

I read Michella Rahurahu’s Poorhara over a three-month period from November 2024 to January 2025 in which I earned $30 in total income. Over this same period, like most artists in Aotearoa, I received rejection after rejection from funding applications and residencies, which is to say that I was constantly texting people things like “Hey I want to see you but I’m too pōhara to do anything.” I spent the rest of my time bumming around doing not much, which stressed me out, somehow paradoxically making it difficult to give my full attention to Poorhara despite having nothing else on My time became financialised, split between the book and the sense that I could or should be doing something differently or better in order to get paid, the continued confusion of tying self-worth to capitalism. This is just to say that from one “true poorhara” to another I read Poorhara at the right time.

Star and Erin are two young Māori driving through rural Aotearoa talking shit, arguing, dealing with whānau members, their history, cops, disapproving white people, their history, too, dogs, the general vibe of the nation right now, and so on, and so on. I’m a young white-presenting Māori who spent most of my months reading the book walking and/or driving through areas of Te Waipounamu Aotearoa. I spent that time talking shit, lots of it about art, arguing, mostly with myself, dealing to the extreme with whānau, not really dealing with the cops but still feeling that firm pang of fear whenever a cop car drove by. I’ve never been too keen on state-sanctioned expressions of power and hierarchy or the day-to-day operations of class in the world.

Poorhara has a paradoxical pace: languid and urgent. The novel primarily focuses on a haerenga through the physical terrain specifically of the North Island, less specifically of everywhere the protagonist’s whakapapa has roots on a map.

Rahurahu sets up psychological loaded gun after psychological loaded gun for Erin and Star. Once Erin and Star venture into the physical landscape, they activate it, their psychologically loaded guns go off.

Erin and Star’s haerenga perfectly matched the languid-urgent pace of my own haerenga through an early-twenties crisis of conscience in which I was frequently thinking banal questions like what should I be doing with it? What’s going on with all this junk I have to deal with?

I kept thinking about my experience of all this and landed on the fact that I was being navel gaze-y. I had to deal with Poorhara as an aesthetic experience in its own right. I’d been treating it as an emotional mirror for my own mid-twenties-Māori crisis when it’s instead about two quite specific people going through a quite specific growth period.

Erin and Star’s journey across Te-Ika-a-Māui resembles a traditional Bildungsroman. It’s an unmistakably Māori one, though: a traditional Bildungsroman requires a changing of terms, a ‘coming of age’ through transformation. In Poorhara, the growing up takes place through whakapapa, conceptualised broadly through Erin and Star’s relationality to the narrative, to other characters, to their whānau and whenua. In Poorhara, the ‘coming of age’ happens through going back to where you were from before you came of age, maybe before you came into the world at all, going back to all that took place before you even could come of age.

Poorhara is a novel about being overloaded by the past and all the baggage you’ve accrued. In a very Māori way, it is also a novel in which the characters have to enter deeply into their accrued baggage in order to suss it all out. Take, for instance, the chapter A TOKI TO GRIND, in which we learn that Erin “would fight anyone, big or small…[s]he would only ever get one stab, one hit, one knock in before she got caught, so she got pretty good at making it count.” This “aura of hostility” is echoed by Erin’s Aunty Huia, who Erin relates to yet also “did send a letter with a message along the lines of I hate you for ruining everything.” Rahurahu introduces what seems like a metaphor, the idea that Erin “would sit like a faithful dog at Huia’s feet.”

In A TOKI TO GRIND, Erin visits Aunty Huia and learns (or rather gets told to learn) the unpleasant lesson that “whakapapa exists whether you like it or not.” Throughout this sequence, Rahurahu makes a beautiful alchemical transition in Erin’s ontology as a character. Remember that metaphorical imagery, about Erin sitting at Huia’s feet? By the end of the chapter, the metaphor becomes literal: “Huia sat on the couch and Erin sat by her feet on the floor.” This alchemical transition from the realm of the symbolic world to the material world characterises the book.

Poorhara’s alchemical nature is designed to be explored, waded through, as the journey for the reader echoes the journey of the characters. You just have to submit to the road. Rahurahu’s layering of minutiae ultimately means the novel culminates as a convincing portrait of contemporary Aotearoa, lived in and nuanced. It’s hard to imagine the book resonating with an audience beyond those who have lived in Aotearoa, but it’s about time we started viewing this as a strength rather than a weakness within our literary scene. Why not bolster our localised arts ecology? Why not write books for us, in this country, and nobody else?

A friend of mine who works at Scorpio Books told me they loved this book but have had a hard time moving it off the shelves because it’s sad. This is your sign to go out and buy the damn thing—Rahurahu’s Poorhara is an important novel working in a wider lineage of Māori writers exploring the relationality of things. It feels like a book not just by but for Māori. Reading it, I couldn’t help but feel I was immediately watching the novel establish itself as historically important. It sits in my imagination right alongside writers as significant as Witi Ihimaera, Keri Hulme and Patricia Grace. If I were to create a canon of Māori literature, Poorhara would be its most recent addition—it may well be the best novel published by Te Herenga Waka University Press in 2024.

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua.