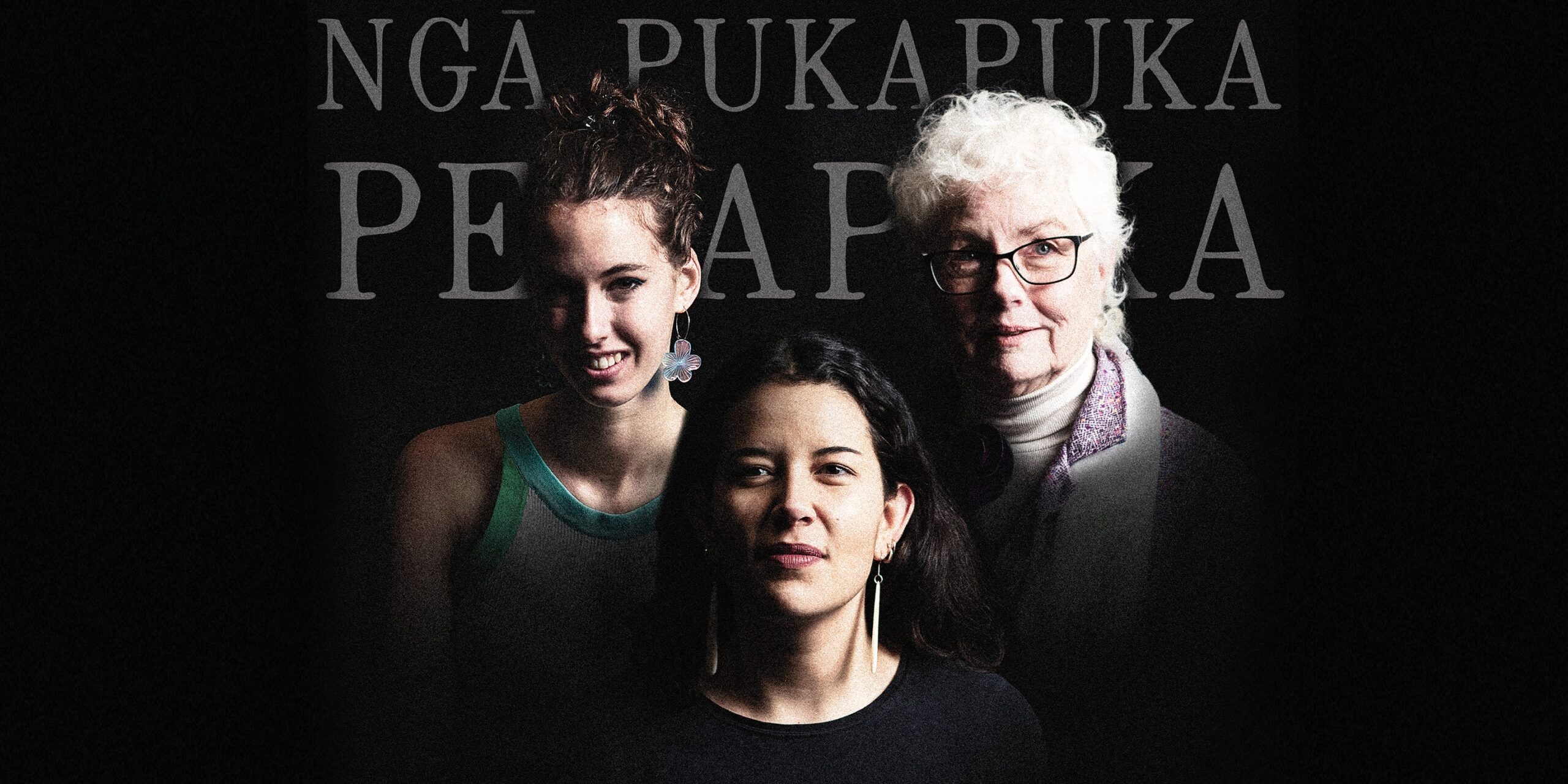

It’s always exciting to see a new independent publisher emerge on the scene, especially one that takes a fresh approach. Ngā Pukapuka Pekapeka is new to publishing in Aotearoa but its editors are not. Isla Huia, Laura Borrowdale, and Josiah Morgan have all had books published, interestingly, with Dead Bird Books, an independent press based in Tāmaki Makaurau. Describing themselves as a press for “chapbooks that push the boundaries on the page and the stage”, Ngā Pukapuka Pekapeka released their first trio of chapbooks at the end of 2024, all around 40 pages long.

The press has a bold aesthetic that comes across clearly in its marketing, particularly in its carefully curated Instagram grid with a desaturated, gothic palette and excellent vampy vibes. But aesthetics aren’t everything, so it’s encouraging that Huia, Morgan and Borrowdale are all experienced writers with an impressive collective background across various disciplines.

Their debut publications are from three emerging writers living in Aotearoa: Molly Laurence, Ruby Macomber, and CR Green. All three are first books, and the chapbook form allows us a chance to sample the work of writers who have a cohesive body of work but perhaps aren’t ready for a full-length collection. A chapbook can also give a writer the chance to delve deep into a specific theme without needing to expand it across a longer sequence–some topics lend themselves to a punchy, self-contained work that you read in one sitting.

CR Green’s Introduced Species tracks across 17th century America to current-day Aotearoa, tracing Green’s journey from one colonised space to another in abstract. She follows her ancestral lines through the centuries, beginning with a poem in conversation with an ancestor 12 generations back, a family history previously unknown: “This is your mother’s branch / where eggs wait for seeds.” It’s a violent story, the woman’s mother and brother kidnapped and put on a slave ship to Africa, her father murdered. In opening with this dialogue, Green tells us that hers is not the only voice we’ll be hearing through this book—in many ways, it’s not even the most important. The title suggests a collective rather than an individual, and carries the implications of the other word often used to describe a species not native to a place—invasive.

Introduced Species weighs more heavily than you’d expect from its slim 44 pages, but there are moments of levity too. In a short prose piece that I assume is non-fiction, the speaker describes meeting Groucho Marx at a club in Hollywood where her husband is working on a show. When she tells Marx “I’m just married to the light man”, he replies, “Married, huh? … I didn’t know people got married these days”. The 80-year-old Marx then strolls off with his disturbingly young girlfriend. This slightly odd, offbeat piece nestles between a poem about schooling in the USA at the height of the Civil Rights Movement and one about recording songs with her husband as “a couple of Jesus freaks”. Within a few pages, we’re presented with a wide spread of ideas, bumping up against each other and seeing how they fit together in the space of a life.

In contrast to Green looking back over her years, Molly Laurence’s Parallel Lines celebrates and explores the right now of a high school student, on the brink of stepping out into the world and brimming with ideas. We sit with Laurence in classics class as Homer’s doomed heroes sit alongside her and her crush, considering the way stories get misconstrued and omens misread:

Myths are not necessarily true. It was

probably [maybe] / an accident. Things will be

weird / from now.

Where Laurence’s work shines most is in her investigation of the whenua and our existence on it. In the titular poem, lines from Aquamonotrix packaging (a product for measuring nitrate and nitrite in water) are woven in with Laurence’s own words and quotes from her father to explore a complicated relationship with the land on which they live. The stream in the garden and the powerlines above map out two seemingly disparate but actually intertwined worlds. The jargon-filled copy of the Aquamonotrix packaging matter-of-factly states how agricultural runoff “enters the aquatic environment” and “introduces nutrient-rich nitrate and nitrite”, skating over the immense repercussions of this pollution with language that feels distant and carefully neutral. Meanwhile, Laurence’s father says it directly: “Nitrates make the water sick. Things can’t live.” It would be easy to frame this problem as us vs. them, Laurence’s family in the good camp against the dairy farmers in the bad, but the poet allows for nuance, and the poem is better for it. Describing her brother as “the Fonterra lad of our house”, we then end on an image of the two men throwing rocks from the river up at the power lines, a scene of camaraderie and aimless joy. The problem expands to encompass the writer and her family as well as the reader, all of us together on this land, watching the river run.

Having enjoyed Ruby Macomber’s work before, I was most keenly anticipating her chapbook My Moana Girls. Macomber opens with an epigraph from “a boy from Tinder”: “Are u like, a chill moana girl or should i be scared?” She proceeds to show us through her poems that she is very chill, and he should be scared. In My Moana Girls, the cool girl vibe contains praxis. The pop culture references feel both exaggerated and self-aware: “Curl Karl Marx around our fingers / ask him for his star sign” (‘My Moana Girls’). The opening poem asserts, “we dance Moana duality / cos Paul Mescal is hot. / but Tayi Tibble is hotter.”

There’s a sincerity and a softness there too, a pushback against the insidious idea that brown women are scary; must always be strong. In ‘Cry Sis’, a pun on the word crisis in response to Earth reaching the 1.5-degree warming threshold despite the 2016 Paris Agreement’s pledge to stop this from happening, Macomber writes, “you can cry, sis / because our Moana grief / clings to the coast more with every blind eye”. This vulnerability is another kind of power, as Macomber explores in ‘Carved Baddie // Hine-ahu-one’s Girls’:

Ask your tūpuna whether they will love you for what you are

not resent who you are notYou skim your sisters’ streets in solidarity

shoulder

to shoulder holding morethan our mothers bargained for

All three of these collections are promising starts, the beginning of conversations with lots to still be said. It’s tricky to round out your ideas fully in just 40 pages. Every line feels like it needs to be doing its absolute best, which is a hard ask. I’m excited to see these poets develop their work further, these first publications being an excellent starting point to jump off from and speak back to. Likewise, I look forward to the next round of chapbooks from Ngā Pukapuka Pekapeka as they continue to explore the possibilities of this form, hopefully, bolstered by a successful first run!