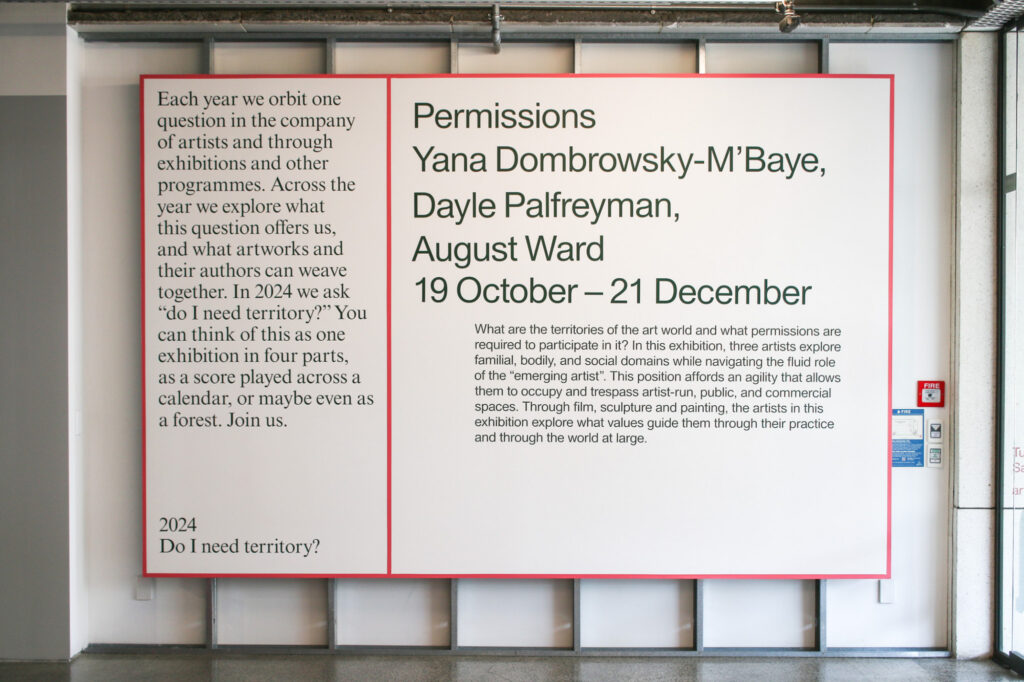

Putting forward its annual question into the world, Artspace Aotearoa has prompted artists and patrons alike to consider “Do I need territory?” throughout 2024. For the final exhibition of the year, Permissions, this prompt is put forward to Yana Dombrowsky-M’Baye, Dayle Palfreyman, August Ward. These artists of the 2024 Chartwell Trust New Commissions programme “are at the stages of locating their practices in relation to their worldviews while orienting themselves as “emerging” through various art world territories.”

For bad apple, Jo Bragg brings Dayle Palfreyman into the shared territories of arts writing and digital archives through an interview about their featured works in the gallery.

Dayle Palfreyman recently moved to Tāmaki Makaurau from Te Whanganui-a-Tara, and works across sculpture, installation and video. Dayle’s sculptural practice has primarily used metal, concrete, wood, and beeswax to create environments that explore the edges of bodily autonomy through the tensions between the industrial and natural materials employed. Dayle graduated from Massey University in 2020 with a BFA (Hons) and has had exhibitions at play_station in 2020, City Gallery Wellington in 2022, at Enjoy Contemporary Art Space in 2022, and 2023, and the Physics Room in 2024.

JB: Kia ora Dayle. Thank you for agreeing to be interviewed for bad apple.

As part of the Chartwell Trust New Commission Programme 2024, your sculptural works Limbo and Running Around the Sun are currently on show with Artspace Aotearoa (alongside works by Yana Dombrowsky-M’Baye and August Ward).

Let’s open by talking, first, about material. You mentioned during a floor talk I attended that you like the simple language between the industrial (steel) and the natural (beeswax).

The beeswax smells incredible and adds an extra sense (perhaps sensual) element to the experience of the works. Can you expand on your decision to use these materials and maybe tell us a bit about the fabrication process?

x 29 x 21 cm. Detail.

DP: I’ve been using both metal and beeswax for almost 5 years now. I learned new ways of approaching both of those materials over the years and have found them to be a useful conceptual framework. For example; finding tensions between “natural” and industrial frameworks, considering systems of politics within the hive and also the realm of the divine that bees are closely associated with – as part of a wider interest in anthropomorphism and anthropocentrism.

This iteration of beeswax bars used in the work were part of an earlier iteration I made over the summer at the beginning of the year and late 2023. In 2024 I made a 10-metre-long beeswax bar and worked with a metal worker to fabricate the stanchions in Tāmaki. The beeswax bars were arduous but rewarding and the ideas developed in the earlier iterations were seminal for what I made for Artspace Aotearoa. I also cast three objects in both bronze and brass.

Under the suspended beeswax bar in Running Around the Sun, lays the concrete block with a drain plug in the centre, this drain plug was made with 3D modelling processes and cast in brass. In Limbo the top and bottom vertebral pieces being the sacrum at the base and the atlas at the top, are suspended upside down in beeswax. These works were hand-carved in wax and cast in manganese bronze which is a colder bronze.

After working with beeswax and metal for many years I feel like it makes sense to engage with the art tradition of how those two materials have commonly been used with carving wax and casting that in metal.

For the drain plug, I wanted to go through a fabrication process but also wanted it to be an exact copy of the drain plug I could find in any bathroom, hence using 3D modelling. I wanted to use concrete for its perceived weight; the flat base was to tempt the desire to stand inside without being able to.

JB: Speaking of material, your work approaches a kind of abstract formalism. What I’m trying to say is, I guess you could just leave it up to the material to make the meaning. Yet, you are very generous toward the works in your research and application of literary references, which I adore, obviously.

For example, the titles of these works are a conduit, or vehicle, for the state of ‘limbo’ described in Purgatorio (or Purgatory), the central canto of Dante’s epic 13th-century narrative poem The Divine Comedy.

I have only ever read the first canto Inferno, the one about the nine circles of hell. I should probably get across the finale Paradiso (Paradise) this summer. Anyway, your work was my introduction to Purgatorio. Can you tell us about the influence of Dante’s description of ‘limbo’ and how this relates to these works?

DP: The description of Limbo in Canto IV captures a state of separation and longing, “That without hope we live on in desire”. Limbo is the first circle of hell, more so mentioned in Inferno but talked about in Purgatorio. “Have not the sound of wailing but are sighs” (Canto VII), limbo is described not as a place of suffering like the rest of hell but as a lack of “divine grace”, which is the only way to salvation.

There’s a few things that led me directly to this reference. Agamben’s ideas around bare-life and research around the judiciaries negotiated in the after-life. Bare-life from what I understand, is where people are cast out of the society yet still subjected to its power. I thought this tension around judiciary subjugation negotiated not only in society but also in the afterlife was really interesting, as someone who focuses on power dynamics. In Purgatorio there are questions around free will where individuals participate in their own purification unlike Inferno where you have no choice in the given fate, as well as Purgatorio being the realm of hope. Ideas around free will explored through the concept of bio-power and subjugation are ideas I’ve explored in previous works of mine.

Limbo and Running Around the Sun point to states of exception in ideas around the afterlife talked about in The Divine Comedy. Both works are placed in states of suspension in two different ways, alluding to suspension being both a mode of subjugation brought out by the structure of metal, and protection, as beeswax is known for its healing, preservation and divine qualities. The work poses questions and aims to accentuate tensions around how the body and soul are governed.

For the work Limbo I placed the sacrum and the atas upside down in the lectern. I wanted an element of subversion, where the bone and its associations with the rectum, reproductive organs and urinary tract lay at the top rather than the altas with its association with the mind. It also emphasises the suspended body as you imagine a body upside down in the pool of beeswax, there’s an immense vulnerability there within its supposed support systems. Much like Dante, I wanted this blurring of the afterlife and the physical realm to be pressed up against each other.

JB: In Dante’s Purgatorio, the fate of those who committed sins of homosexual lust and desire (his words not mine) are to spin in purgatory counterclockwise around the sun. Notably the opposite way to heterosexual souls who committed the same sin (again, his words not mine). The structure of Running Around the Sun (2024) suggests a shower-like structure. There seems to be a clear conversation occurring around direction, location and orientation. You mentioned biopolitics. Do you think a lot about authorship in the making of your work? I sense a tension at the boundary between public and private, or maybe it’s the body and the psyche?

DP: I think a lot about both authorship and power structures, informing the form and also how I talk about the work. In terms of authorship, I think about the people who help me make the work and, also, the research and writing that helps develop the concepts that support it. I often like to nod to writing that has helped shape the work through titling, aiming to facilitate discourse and helping to make certain connections a bit clearer for the audience.

We do not create alone and nor should we, so I aim to make that clear when I can.

Running Around the Sun develops on a previous work that focuses specifically on the bathroom as a site to study political boundaries of public discourse and private bodily autonomy. Thinking about a private space that deals explicitly with the body. Similar to the ways in which religious ideologies can imbed themselves into the psyche (into a private space) and affect what we do with our bodies.

I wanted to engage with ideas around lust in the context of condemnation. This visual of souls both running around the sun (the divine light of cleansing) in different directions depending on your sexuality. I found both beautiful and an interesting point of tension. On one hand, it offers the homosexual soul an opportunity for redemption through purgatory, on the other hand, it reduces homosexuality to a physical lust perhaps for its nature devoid of the “divine cause” of procreation. I was thinking about these early 14th-century ideas in relation to the topic today, where rigid ideas of gender and sexuality still populate politics and our everyday lives.

I’ve looked at the bathroom as a site for both political discourse and also expanding these conversations to a more poetic dialogue as well. This is a site I’ve been interested in for a while and will continue to build off of this site.

Makes me think about the French writer and photographer Herve Guibert. Where he writes about the effluence of the sick body, making the sick body a site of public discourse and control while stripping it of its dignity. I just made that connection now, I was part of a show at Enjoy Contemporary Art Space in Pōneke 2023 which was a curatorial response to his text To The Friend That Did Not Save My Life.

JB: That answer was so stunning, thank you so much. In a preliminary conversation in preparation for this interview, you mentioned finding a dead bee. How this sparked a deeper engagement with the way your work relates to notions of materiality. Like, thoughts around the corporeal body as material vs the spirit and how this relates to immaterial forces like desire and, therefore, power

Not that the body and spirit are competing forces, rather, both are non-negotiable ‘embodiments’ of a kind. I am paraphrasing horrendously, but wanted to know your thoughts, if any, on a turning (back/toward) queer spiritualism in contemporary art?

DP: I’ve been very interested in this sort of linguistic breakdown of the body and the spirit and how that manifests within politics and philosophy. Previously focusing on an idea of “the reduction of flesh” as a subversion of totalitarianism which reduces the body to flesh. Most recently coming across Agamben’s concept of bare-life which derives itself from the Greek words bios (having cultural and political meaning) and zoē (biological fact of being in a body).

Bare-life being zoē stripped of bios, where there is no political or cultural being. My work over the recent years has explored the aura within the work sparked by my findings of the dead bee and interest in politics’ intersection with spirituality and mechanisms of control.

This idea of queer spiritualism for me is only a recent discovery and I think speaks to one’s own desires and understanding of what that is. My friend Tom Denize would talk about his work around finding sanctity in queer spaces like nightclubs as a ritualistic process, being my first exposure to the idea. Very recently I’ve been learning more about Derek Jarman’s work, reading his books, and watching his movies. He was the first gay saint of Britain after all, canonised by The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. Queer spiritualism for me brings in the fluid and the subversive that I love so much. In Limbo I’ve juxtaposed ideas around power and the sacred body, visitors are allowed to touch the sacred bones as they lay upside down suspended in beeswax, the sensual nature of this work sits within a context of power, as the lectern holds the position to speak sacred words.

Running Around The Sun speaks to the bathroom as a private space for public discourse, tensions of the body and mind in pro-life sentiment through the guise of divinity. This is loosely how I’ve approached the idea in my own work, not intentionally but naturally. I think queer spiritualism within contemporary art is an act of resistance, as was the case for The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

JB: Absolutely amazing, I’ve really got my work cut out for me to finally read Dante’s Paradiso this summer and finding out more about The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence! So, final question and thank you for your time. Can you suggest a small reading list for those who, also, might like to do further reading? It can be relevant to your work, or just stuff you have really enjoyed lately. Thank you again for your work, time and insight.

DP:

Blue (1993) by Derek Jarman

The Coming Community (1990) by Giorgio Agamben

An Apartment On Uranus (2019) by Paul B. Preciado

Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982) by Audre Lorde

Featured photos courtesy of Artspace Aotearoa.