I’ve been learning how to edit prose recently.

This sounds like a bizarre claim from a writer who’s already published five books, but it’s true. All five of my previous books are poetry books or engaged in poetry-prose hybrid practices. Now, for the first time, I’m working on a novel. I received an early career grant in early 2024 from Creative New Zealand to redraft said novel between July and December 2024. At the time I received the grant, a first draft existed. At the time of writing this article, I am getting close to completing the third draft.

The novel is tentatively titled Kosta, Stella, Āwhina and Taylor (but not Liam) are at the Zoo. It’s an urban fairytale following a group of teenagers living through a suicide epidemic in an alternate-reality post-earthquake Christchurch. The teenagers begin experimenting with a psychedelic drug called Lingo. When they take the drug, the teenagers believe they can speak to animals. Concurrently, two police officers attempt to raise public awareness about the drug and reduce the impacts Lingo is having on the community. The book is primarily about Christchurch and how the city has responded to trauma. It is also a novel about climate change, the Aotearoa mental health crisis, systemic racism and the other ways that bureaucratic systems treat people differently.

I’m deep in the mires of the novel, so I can’t tell you anything about its quality right now, but I am confident that the third draft is significantly better than the first. This comes down to practice and actually activating the advice of other writers including Laura Borrowdale, Ben Herriot, Jade Young and David Herkt.

Here’s the first paragraph of my novel in its first draft form.

Here it rained. Liam sat outside on the balcony at his father’s property on the Cashmere Hills. Taking a drag from his cigarette, he thought that the gridded geography of the city looked like a Mondrian. Flat, level, square. His gaze settled on the sparkling houses below, which were unblemished by shadow or chimney. They looked unlived-in. Merely inhabited. Each was uniform and autonomous and suburban. An echo of the natural world still spoke to Liam through the sprawl. The swamp was still there underneath the city, wet and deep and seething and large, making Liam’s Christchurch a zone of perpetual transition. He inhaled smoke, feeling his chest warming and expanding to make space for this place with its damp, its concrete and its growing and growing.

I still find the imagery here evocative, capturing Christchurch in a way I don’t often hear in literature. The wording is, however, a little clunky. The paragraph wants to position itself as ‘from Liam’s perspective,’ yet the omniscient narrator has too much power.

The first draft of the novel took place out of order, each chapter following a different character traversing the Christchurch terrain across a school week.

One of the key things I’ve been working on between drafts one and three is shifting the narratorial voice so that the omniscient speaker only has the same information as the characters. In short, I’m moving closer to something like free indirect discourse, though without the psychological insight.

Here’s draft two, which shifts the chronology slightly:

Liam and his father sat on the balcony together, neither exchanging a word. Their silence was comfortable; it gave Liam time to think. From this vantage point high in the Cashmere Hills, the roofs of the houses below sparkled in the brief afternoon sun. Most of the houses looked arbitrarily inhabited and barely lived in, uniform like autonomous individuals trying to blend in with the rest of the suburban sprawl. He thought that the gridded geography of Christchurch City looked like the Mondrian painting that he had been studying in art class. Flat, level, square. Yet Liam still heard an echo of the natural world through the concrete sprawl. The Christchurch that Liam belonged to was a concrete scab on top of something wet, deep, seething and large.

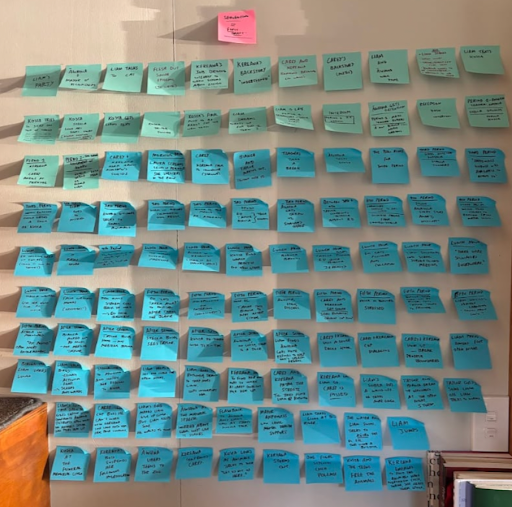

My goal in the second draft was really to clarify what, precisely, I was communicating. One of the clarifications needed was at the structural level. I laid out each beat of the novel in sticky-notes so I could see how the novel was moving. It became clear to me that I needed to change the structure entirely so that the book took place chronologically. The chapters are now far more simply demarcated: the novel begins with a chapter called Saturday and traverses the entire week through until Friday. There is a format and tense change in the final chapter, titled This Week, and then the book ends.

Once I completed structural changes, which included removing entire chapters, writing new chapters, rewriting existing chapters, and changing the order of certain scenes, it was time to think about how the book worked on a line-by-line level. I wanted to maximise the efficiency of the prose and begin to seriously craft this free-indirect voice.

Here’s draft three, the state the book is currently in:

From above, Christchurch looked like what it was. A concrete scab. Flat. Level. Square. Suburban rooftops sparkled in the brief afternoon sun. An echo of the natural world spoke through the concrete. The swamp was still there underneath the city. Liam looked at the suburbs to avoid looking at his father. They sat on the balcony together, neither exchanging a word.

To me, this starts to resemble something with legible intent.

Writing classes around the world bang on about the difference between passive voice and active voice, but it’s not always easy to understand how effective active voice can be until you see it in practice. Stephen King says one of the words to avoid in writing is “was.”

Here’s an example from the first draft:

Whilst Ed was distracted [smoking from the bong], Taylor punched him in the head.

Here’s the third draft:

Ed inhaled. Taylor punched Ed in the head.

It will be obvious to anybody reading this essay that my intent with the novel is to clip the prose so that the novel’s register is straight up. In its third draft, the novel mostly takes place in clipped sentences with typical subject-verb-object constructions. One of the reasons for this is so that language can truly bend and warp in the crucial drug trip sequences. Here’s the third draft iteration of a scene in which Liam takes Lingo. When characters are high, the novel’s sentences unfurl into long run-on constructions:

The water washed this swamp of its city-shaped scab and he knew that Christchurch would soon return to its essential sparkling state as the sky rained upward to the concrete hugging the Avon which flowed like altostratus clouds above its universe of Myriophyllum triphyllum and Myriophyllum propinquum, both of which stayed rooted in the water as they had been rooted even before Tuna o Ruka i te Raki became Kōiro and as they would stay rooted forever even after no humans or animals were left to observe them, so Liam knew he had fallen from Heaven into a new Earth in which he would live forever and in which nothing, not a promise, not a swamp, would be repressed by concrete ever again.

I’ve scrubbed a narrative spoiler from that above sentence, but you get the idea. All this is to say that the function of prose in relation to narrative has been on my mind recently as I’ve been learning about how it interfaces with my own practice.

Intersecting with my writing practice, of course, has been a practice of reading. Some of the helpful spurs to work on my novel have included work by Diane Seuss, Emma Cline, Ceridwin Dovey, Daniel Kraus, Alexis Wright, Tennesse Williams and also undertaking rereads of Sally Rooney’s first three novels.

I have been, to date, one of Rooney’s acolytes. I would happily vote for Normal People as the finest traditional novel of the twenty-first century. Her first three books are sincere but not over-earnest extrapolations of the relationships between people and capital in a strongly realised and clearly articulated contemporary Dublin. In the first three books, pretty much every character is a writer, and they can pretty much all be read as proxies for Rooney in one way or another.

So, like many, I spent the weeks in the lead-up to the release of Rooney’s fourth novel Intermezzo anxiously counting down the days until I could read it. I placed a pre-order for the novel and was there as soon as the bookshop opened on its release day.

Broadly and briefly, the book follows two brothers coping with grief after the death of their father in different ways. Ivan is a prodigious chess player and enters a new relationship with an older woman. Peter is a high-flying human rights lawyer who indulges in alcohol and sees two women at the same time. Unfortunately, I haven’t liked Intermezzo, at all.

A huge part of this is my own present aesthetic inclinations. Here’s a message I sent to one of my writer friends, the Australian Luke McCarthy:

Bro are you kidding me?? “DAMP SOFTNESS IN THE CROOK OF HER ELBOW HE TOUCHES.”

This kind of outrage at the sentence-by-sentence construction of Intermezzo plagued my reading of the book. Because I’ve been so attentive to sentence-level constructions in my own work, I couldn’t stop myself from live-editing Rooney’s latest as I was reading it. This raises important questions about the relationship between writing and reading. Right now I’m interested in concision and clarity, whereas Rooney is clearly branching out into new forms of exploration involving repetition, the looping of ideas, and the relationship between human consciousness and narrative interpretation. It may just be that I’ve met Rooney’s book at a poor time in my own literary practice and that our aesthetic sensibilities are not overly aligned right now.

Let me demonstrate what I mean. My issues with the novel really clicked into place one day when I was messaging Laura Borrowdale about it and said the following:

This character intro is awful. It reads like how I write my first drafts when I need to reveal a character to myself.

Here’s the Rooney character intro in question:

No stopping him: Ricky Fitzpatrick: Margaret’s ex-husband. Margaret Kearns: Mrs Richard Fitzpatrick, once.

Intermezzo regularly uses repetitive sentence constructions and the slipperiness of information to emphasise how characters think about situations—I get it. But in my own writing at the moment, I’ve been learning to reduce unnecessary or redundant detail. As a result of this development in my practice, the core issues I have with Intermezzo are primarily aesthetic. I have been attempting to clarify my narrative and boil information down to its most base constituent parts. The edits I am undertaking are a process of shrinkage, where anything tautological is removed from the text and everything only needs to be explained once. Rooney’s book is interested in consciousness (like many of the great Irish writers before her), and consciousness in literature is almost always tautological and repetitive. Take a look at the Rooney sentence above: Richard/Ricky Fitzpatrick’s name is mentioned twice. Margaret’s name is mentioned twice. The word “ex-husband” is doing the same work as the past-tense word “once.” There are a lot of doubles in this construction, meaning that as a reader we experience the same information twice in rapid succession. Intermezzo is plagued with moments like this.

Here’s an example from my first draft of myself doing the precise thing that bothered me in Intermezzo:

“Yeah. Alright,” Liam had replied, with a Tuatara Hazy IPA in hand. Then the sky had changed and it had rained. That was it. The first broken promise. Liam knew his dad was incapable of being out of the way. In many ways, being there was one of his father’s primary character traits. Mr. Moore was the mayor. To Liam it seemed that the Mayor’s primary job was to be present, to be visible, to be seen smiling and providing and schmoozing.

Notice that word “had” hanging there in the first sentence, pesky? The word “then” slows down the action too—the sky doesn’t just change, the sentence itself articulates what is already implied. We also get stuck in Liam’s thoughts. Here’s how this passage operates now, in its third draft:

[Liam and his father] sat on the balcony together, neither exchanging a word. Mayor Moore sipped his Cape Codder and wiped a droplet of sweat from his overworking forehead vein.

— It’ll turn nasty tonight, you know, said Mayor Moore. Storm’s rolling in. Best make sure everyone has a ride home from your party.

— Yeah, I’ve told everyone, said Liam as he swigged from a Tuatara Hazy IPA. Doesn’t seem like it’s gonna storm. It’s warm for winter right now.

— Well, fingers crossed. That’d be one way to ring in a birthday. It was stormy the night you were born, too, you know.

— Yeah, you’ve told me like a hundred times.

Their conversation continues for a while, and then…

Mayor Moore’s silhouette overlooked the city. Resentment coiled inside Liam.

— Dad.

— Yeah, Liam?

— Can you just, like, stay out of our way tonight?

— Sure thing, buddy.

— Promise?

— Promise. You guys do your thing. I’ll just stay in my room. He turned to face Liam again. Do you want to do anything before people start arriving?

— Nah, not really, Liam replied.

Having exhausted the necessary organising, they finished their drinks in silence. The storm broke. Liam rushed inside ahead of Mayor Moore, who closed the balcony door behind him. The wild outdoors were partitioned from the shared lounge and dining space.

Liam’s internal thoughts are externalised through dialogue in this third draft version. The storm is no longer something Liam observes as having broken. It just breaks.

Notice in the first draft how I felt the need to say “Mr. Moore was the mayor”? By the third draft, I just refer to him as “Liam’s father” then “Mayor Moore.” This is a kind of semantic trick but because there are only two characters in the scene, the reader can follow along with no problem.

The aesthetic benefit of reducing redundancies and unnecessary detailing is for the reader. As a writer and stylist, I often prefer complex sentences with repetitions and callback structures – I am by inclination a poet, after all. With that said, working within the framework of narrative propulsion has attuned my attention more closely to the reader’s experience. For me, when a writer wields information in a heavy-handed way, it slows down my experience of meaningfully engaging in the work. Intermezzo is a prime example.

One thing I’ve recently noticed in my work is that as writers we tend to give ourselves hinges, helpful memory markers to give us a roadmap to what or who we’re writing about.

My novel takes place in a high school. In the first draft, I constantly introduced the principal as “Steven, the principal.” By draft three, he is mostly referred to by first name only, or, on occasion, a sentence only calls him “the principal.” One of the common hinges I’ve given myself falls squarely into the domain of ‘telling, not showing’. Sentences often describe exactly how a character feels, rather than demonstrating why they feel that way. For example:

Carey was surprised when Kereana reached out to hold his hand and squeezed it.

He withdrew his hand instinctively.

There’s that word “was” that Stephen King tells us to avoid. In this sentence, the reader simply gets told Carey is surprised. The sentence is also a passive construction, beginning with “Carey was,” meaning that action gets subsumed in his experience of it. Here’s a simple and obvious improvement:

Kereana reached out to hold Carey’s hand. Squeezed. He withdrew his hand instinctively.

I could remove the adverb there, too, if I wanted to make it tighter.

Kereana reached out to hold Carey’s hand. Squeezed. He withdrew his hand.

It’s possible to condense the action even further here:

Kereana squeezed Carey’s hand. He withdrew.

Here’s Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo, telling us how a character feels rather than showing us:

[Ivan’s] resolution never to see his brother again is, he thinks, a paltry solace for the consciousness of his own wrong. As he makes his way across the canal, it begins to rain, at first faintly, and then more heavily. Bareheaded under the open sky he continues his walk – hair flattened to his head, dripping cold rainwater into his eyes – hating his brother, hating himself, and feeling extremely sorry.

If I apply a butcher’s edit to Rooney’s work with the same lens applied to my own, my preferred edit looks something like this:

Ivan makes his way across the canal bareheaded as the open sky rains at first faintly, then more heavily. His hair flattens to his head, cold rainwater drips into his eyes, a poor balm for his hatred of his brother, of himself, for his sorrow.

Or here’s a version that transitions feeling toward action:

Ivan clenches his fist, walks heavy-footed across the canal. The sky opens. Rains. His hair flattens to his head. No umbrella, stupid. Rainwater drips into his eyes.

It’s interesting to reflect on one’s positionality as a writer. Neither of my edits ‘improve’ Intermezzo by any stretch of the imagination, but they do alter its aesthetic priorities to be more aligned with what I’m interested in right now. And ultimately, editing is just decision-making.

My issues with Intermezzo don’t just extend to the sentence-by-sentence level. I also have serious problems with the novel’s character and plot construction.

The problem with the novel’s characterisation is that the characters are all ciphers, plot machines that encode different ideas and reveal certain biases Rooney holds. Take Peter’s two girlfriends: one is a young manic pixie dream girl archetype. She’s a decade younger than Peter and he sends her money often. She doesn’t have a job and lives in a squat. She seems to be sexually promiscuous given that she sees multiple men and sells nude photographs of herself online for money. Peter’s other girlfriend is mysteriously disabled in a not-very-clearly-articulated accident. We don’t know much about her disability other than that it stops her having traditional penetrative sex. This sets up a pretty clear stereotypical Madonna-Whore relationship throughout the novel. Because the novel is situated through Peter’s perspective, and because Peter is an awful and unlikeable person, the Madonna-Whore opposition is left to be resolved through a character without the moral awareness to meaningfully challenge or subvert the stereotype.

Here’s a message I sent to Claudia Jardine early in my reading:

Ok, so one of my struggles with Intermezzo is something I always get grumpy at other people for complaining about, namely, unlikeable characters. Usually I’m like “what’s wrong with you? Who cares?,” but there’s something I find deeply, viscerally uncomfortable about Peter. I think the reason it’s bothering me so much is that his paternalistic treatment of the two women he’s with in the novel mimics a kind of ableism in his language toward Ivan. And I can’t see a strong distinction between Peter’s character voice and Rooney’s writer voice. I know enough about her politics to assume it might just be a slightly misjudged character voice rather than a reflection of her actual beliefs, but actually just reading into the book itself, a lot of Peter’s assumptions about Ivan aren’t effectively undermined by Ivan’s actual voice in the novel, Ivan’s actual experience. I’m struggling to split out the visceral discomfort of Peter’s assumptions about the world from Rooney’s, which is odd because usually this is one of her skills as a writer.

I stand by this. Peter often thinks of Ivan as someone with only an

idea of friendship

rather than somebody who can attain friendship in reality. He’s constantly thinking about how Ivan must never ‘get’ women, or if he does, thinking the women must be into chess like Ivan. All of Peter’s assumptions about Ivan would be fine if Ivan’s arc meaningfully counteracted Peter’s thoughts about him. Technically, on a narrative level, the book does do this: Ivan is constantly doing things that show Peter has incorrect assumptions about him. But in the way Ivan thinks about himself and his own implied neurodivergence, all of Peter’s negative assumptions are affirmed:

[Ivan] breaks off here, not having prepared in advance any phrase with which to close this sentence, and not finding now any appropriate one to hand.

Whilst the actual plot of the book moves in opposition to Peter’s poor moral judgement of Ivan, Rooney’s actual authorial voice is too guilty for me of siding with Peter, a character I just couldn’t stand.

Applying this same critical lens back to Kosta, Stella, Āwhina and Taylor (but not Liam) are at the Zoo leads me to account for my authorial voice. A key subplot follows two police officers as they navigate a public awareness campaign about Lingo. Systemic issues in the New Zealand Police are stark; global police institutions are fundamentally racist. In opposition to this, the fictional apparatus of the novel demands that the two police characters are identifiable or even ‘likeable’ in some way or another. Rooney’s treatment of Ivan in Intermezzo has me looking at my draft again, considering whether my authorial voice carries a clear enough position on these characters or not. For me, it would be ideal if the novel’s authorial voice could hold a clear ethical position without making direct or didactic political statements.

It doesn’t help that Rooney’s Marxist inclinations are part of the problem in Intermezzo. In previous books, Rooney does an excellent job of articulating the relationship between people and capital, in particular demonstrating class differences and the different types of labour that characters can sell.

Rooney is right that, in the contemporary capitalist world, we’re all deeply embedded in networks of relation. The problem is that Intermezzo’s class commentary is entirely sublimated into disabled cipher characters who are reliant on the other, more able people around them. It’s as if Rooney has taken the cliché Marx quote “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need” to a horribly presumptuous endpoint.

In Intermezzo, a mysteriously disabled woman is reliant on a rich man who treats her poorly.

In Intermezzo, homeless youths are reliant on the same rich man to get them out of their situation.

In Intermezzo, a young manic pixie dream girl fulfils the ‘whore’ archetype and relies on the same older rich man to pay her bills.

In Intermezzo, an autistic-coded man, Ivan, relies on the same older rich man, his brother. When the novel finally allows Ivan to break free from Peter’s narrative trap, Ivan is still reliant on all the other people around him.

The world is richer than Rooney’s imagining of relations in Intermezzo. The task ahead for me is to account for the richness of the world in my own imagining.