E āku mokopuna

ānei taku karanga atu ki a koutou,

he karanga aroha, he karanga manawanui.

E nono mai rā ki te whāriki nei,

te whāriki aroha

Sometimes it feels like there’s as much pressure on us to be good descendants of our ancestors, as there is pressure to be good ancestors to our own descendants. This can feel like an immense way to measure the successes and challenges we face daily, monthly, yearly, always.

It’s also one of the few ways we can be placed safely amongst the intergenerational wisdom of our whakapapa. Being positioned in equal measures old and young is what keeps us connected to the natural world from which we are sprung—we grow and evolve in a perpetual cycle of birth, death and living in between. Whakapapa is our relationship to both our innermost selves and our wildest dreams. It is the liminal space we live within.

Whakapapa is a spectrum that reaches as far back as it does forward—we stand looking backwards so that the world may unfold behind us. We are already future ancestors, where whakapapa has no gender, elitism, nor hatred. The movements we make in our own lives are proof that change can lead to something better.

The impact we make and the legacies of those we descend from are further proof that whakapapa is never truly broken—it exists in states known/unknown, named/unnamed, connected/disconnected. It moves through generations and lifetimes, making room for genealogy and whāngai—it is the embodiment of love above all else. There is pain amidst beauty, trauma amidst strength, all of which is captured within the entire spectrum of interconnected human experiences. And we humans are experts at reinventing life—with every new generation we spring forth a new vision for a better world.

In this personal essay, I briefly discuss some of the ways in which my whakapapa Māori and experience of takatāpuitanga are intertwined. I hope that, in sharing the whakaaro I was gifted by my kaumātua, those who need to find solace and security in their own takatāpuitanga and Māoritanga can read this and see themselves reflected within it.

I also anticipate that it will be agitating for some—I have experienced a great deal of privilege on my haerenga to reconnect with my whakapapa and reclaim my queerness. I don’t proclaim to be an expert in anything but my own life, and encourage those who have different whakaaro to the ones presented here, to seek safe discourse within which to explore the things that may arise.

I also want to acknowledge the deep pain that many have experienced in trying to synthesise their cultural, sexual and gender identities. There are too many horror stories lived within our communities that should never have had to occur—and shouldn’t continue to occur now, knowing what we know about decolonisation and intergenerational harm. Our whakapapa should be the safest of spaces for us, and it’s a disservice to our culture when it isn’t. (I’m talking directly to you here, Mr. Tamaki & Co. We see you.)

I posit here my experiences only to show how different life can be for our mokopuna, as my kaumātua have done for me. I do this, not to draw attention to the divide that exists between our encounters, but to contribute to the wānanga we are having about our community and the spaces where it intersects our culture.

It feels important to share that I didn’t grow up beneath the maru of my own ancestors, or connected to my own people and whenua. I was privileged to grow up amongst those who chose to love, keep and protect our whānau. I was further privileged to reconnect with my whakapapa as an adult and discover a plethora of beauty amidst the pain. He mihi aroha tēnei ki ōku tūpuna.

Along this road, I have learned that from within the vast context of whakapapa, we lay each of our lifetimes upon itself, evolving and finding threads to enrich life along the way.

This is what I have been taught, and this is what I teach.

Part One: The Whāriki called Love

Oh my mokopuna,

I hope this finds you somewhere warm,

some place soft, like the edges of my breasts where your parent fed,

or with your belly full of some kai I taught your matua to make for you,

you, with your mind full of ideas and your heart full of love.

Most of the time, we’re taught a very colonised view of genealogy. We’re given the impression that it’s a linear transmission of DNA that is based on two organisms combining to create one. However, I have been taught that the concept of whakapapa isn’t about a linear progression, it doesn’t exist in a ‘two people = one person’ metric.

From the kōrero I’ve been given, whakapapa is a layering of multiple lifetimes, more like a web that connects the organisms that made you, to the organisms that made them, to the other organisms they made, and so on and so forth.

In this way, the characteristics we’re imbued with don’t arrive in our bodies directly from our parents. They arrive by osmosis from the wider web that they spring from, gifting us the wisdom of aunties, uncles, grandparents, great grandparents and all those who existed in the lines preceding us—not just from up to down, but from generations sideways, up, down around and back again.

The transmission of whakapapa is a spectrum that includes multiple generations, characteristics, challenges and strengths. I like to think that the ultimate proof of the fluidity of whakapapa and its generosity lies within the pre-colonial, non-gendered names we have for those we descend from—mātua, kaumātua, tāua, whātua, kahika, kōhika etc.

Within this framework, we are descended from all of the organisms who share our DNA, not just two humanoid biomes that happen to make us. My own whānau history has taught me that, through this system, love is the centre of whakapapa. It encompasses whāngai, adoption and genealogy. The love we create in our lifetimes and the love we nurture for those we learn from and those we teach is the very fibre our connection is woven from—we are but threads in a very long, ever-evolving whāriki called Love.

It’s within this whāriki that our ability to be takatāpui ancestors and uri is solidified. An ancestor is not someone that ‘birthed’ or ‘inseminated’—an ancestor is someone who came before you, whose DNA and characteristics you share. In this way, you can be imbued with the mana of those ancestors, whether you descend ‘directly’ from them, or are a branch of their whakapapa.

The practice of whāngai has long given those who cannot reproduce by their own organs a chance to contribute to their whakapapa. It has for thousands of years, and continues to exist within te ao Māori, as it does across Te Moana-nui-ā-Kiwa. It is an incredibly beautiful practice that enables many to share in the important rearing of children within their immediate and wider whānau units.

Over the years, I’ve taken comfort in the knowledge that our pre-colonial takatāpuitanga was completely naturalised by our whānau, hapū and iwi formations. Many have conducted research to prove this, including renowned rangatira Dr Elizabeth Kerekere who famously stated that: “Takatāpui were part of the whanau, we were not separate, we were not put down, we were not vilified for just being who we are.”

Many takatāpui tūpuna were given tamariki by their whānau members. These tamariki were raised by them and they were often privileged by access to takatāpui matua who were fonts of whakapapa knowledge and mātauranga.

It’s commonly accepted that pre-colonisation, our people never raised children in isolation. The concept of a nuclear family was as foreign to us as the existence of a single God. Our tamariki were (and are) raised in diverse whānau units, where their natural inclinations were celebrated and harnessed to be used to support the wider hapū and iwi.

“Early European visitors noted Māori children being indulged by their parents and leading carefree, playful lives. Children were seen as the responsibility of the whole whānau, not just of their mother and father.”

For me, being an ancestor and an uri is about maintaining the integrity of that system. That’s each of our responsibilities within our wider and immediate whānau. We bring characteristics into our whānau that will help our mokopuna know not just who they are, but what they’re capable of. And we live our lives learning who we have come from and what they dreamed for us.

No matter how we came to be, we are the finely woven threads of love that bind those who have been and those who will come together.

Part Two: Binding the Whāriki

Oh, my mokopuna!

I hope you know how hard I lived for you—

how I would whiri your smiles into your parent’s hair,

the strands falling between my fingers and with every generation a new curl could form,

how my own hair trailed so far down my back that you could whiri yourself into it—

inverse the Māui and sink into the makawe made from my head, to yours.

Our own pūrakau1 reflect the trials and tribulations of our atua2 in a variety of ways—these stories are cornerstones upon which our lifelines are formed. They show us the way, show us the pain, show us the strength and bring us through our own short lifetimes to retell and nurture, reframe and represent. We seek ourselves, our tribulations and our potential wisdom within them.

Amidst all of that, is the pain we experience when we’re disconnected, the whakamā we hold when we learn and the change forced upon us to unravel and disinherit many of the traumas placed in our paths. It feels important to acknowledge that for those of us within the takatāpui community, these connections can be harder to seek. Our world suffered the indoctrination of a manifesto that severely attempted to delegitimise our place in this world. We know this, we don’t need to be reminded of it. Sometimes what I’ve needed is to be reminded that there’s more hope than there is pain.

As the smasher of calabashes and takatāpui icon Ngahuia Te Awekotuku says, there are “. . . graphic descriptions of “sexual joy” [that] exist in waiata koroua and mōteatea which are still performed today, including explicit references to non-heterosexual sexual relations. In one lament, a young man called Papaka Te Naeroa is described as, “Ko te tama iti aitia e tērā wahine e tērā tangata” (A youth who was sexual with that woman, with that man). Crucially, the word ‘aitia’ was later replaced with ‘awhitia’, meaning ‘hugged’ or ‘embraced’ in an effort to ‘clean up’ the lament by translators in the late 1800s.”

The incredulous transition of colonial attitudes towards takatāpuitanga has caused unfathomable amounts of harm. We know the effects of this hatred, they permeate our stories in a way that silences, harms and hides us from the world we were once so naturally a part of. The harsh reality is that it will take generations of re-indigenising to reform our people back to the level of normalisation that once existed within our whānau, hapū and iwi.

There’s a fair bit of ignorance around the tikanga of gender roles amidst this harsh reality. Show me a tangata takatāpui who hasn’t experienced any of that—will our people welcome us back with our same-sex partners? Where do we stand during pōwhiri? Can we karanga?

Can we be kaikōrero? What are our roles on the marae and which atua preside over our realms?

Many of these decisions are made at a hapū or iwi level and unfortunately there is little standardisation of kawa across the whenua. Because of this, our ability to participate in practices of tikanga Māori are sometimes hindered by the prevalence of colonisation within our iwi and hapū. Many of our people were raised by the harmful rhetoric of a patriarchal, Christianised regime, and while they have access to a plethora of kōrero whakapapa, they haven’t often explored perspectives free of this viewpoint.

This is one of the most difficult challenges I’ve observed of fellow tangata takatāpui who are working tirelessly to reconnect with their whakapapa. Part of the innate tension of decolonisation is that we should be making these decisions at an iwi and hapū level—creating spaces that fit the people within our whakapapa as we have always done. It’s not just relegated to the marae of our tūpuna—we experience this when we enter any kaupapa Māori space.

I would love to write a thousand words about how to break this barrier, but I don’t have them. It’s too nuanced for one piece and such kōrero shouldn’t be centralised into a single view point. To put it simply, it’s not mine to write. All I have are examples of those who have successfully navigated that reconnection and been welcomed back into a space where their takatāpuitanga is both normalised and celebrated—and I cannot share their stories for them.

I can only encourage further wānanga amidst the safety of our own community and hope that people find clarity and kindness along the road. This in itself is a reflection of the continued lateral damage being done within our cultural framework. We should be free to have wānanga pertaining to our lived experiences, we should be able to hold a mic to those who have had success in navigating these spaces. But we’re muzzled by the colonial structures that hold us to a Christianised, inherently patriarchal worldview.

I can share that, upon meeting two of my own kaumātua (a brother and sister), both gave me examples of takatāpui whānau members and their roles within that ecosystem. I hadn’t prompted these whakaaro, they came knowing that I would be nervous about how our new-found connection would take this personal revelation. They did so with smiles on their faces, one lit up as she talked about a tangata irawhiti who had many children. The other beamed proudly about his daughter, her darling and their mahi rangatira within our iwi and community.

My own kuia-ī-whāngai was known as someone who had many sons, though she only gave birth once. She was a fierce protector of her boys. It wasn’t until her tangi that we realised that she had been sheltering members of our takatāpui community under her great presence—she was a formidable woman and the strongest bigot couldn’t have wavered her protection.

We are learning with every generation how acceptance evolves. There are so many beautiful ways to be authentic and the older humanity gets the more sophisticated our methods of communicating, transmuting and evolving become. I wouldn’t dare to proclaim expertise in this, being queer doesn’t make you an expert in LGBTQIA+ issues, just as being Māori doesn’t automatically make you an expert in all things mātauranga Māori. And yet, there is intolerance everywhere—from the marae ātea to TikTok, the ignorance of colonial minds is most prevalent.

In the context of binding takatāpuitanga and the reclamation of whakapapa and mātauranga Māori together, all pursuits require an openness to perpetually learning. This is the tension experienced in the binding of our whāriki—we hold tight to the threads of our world and hope that what we are creating leads to something beautiful and safe for those who follow us. We contribute to the creation of something better than we’ve ever known. But when we do so with our indigeneity in hand, we are often equally reviving something beautiful that was known before.

Our art is a huge piece of this puzzle. There is evidence that our ancestors carved gender affirming tupuna and depicted same-sex relationships in whakairo. How much of our history was stolen by the indoctrination of the Western, Christian agenda? And how do we tell this portion of our story to our uri, whilst encouraging them to maintain the beautiful vision of a re-indigenised, diversity-reformed world?

In the absence of our normalisation, we often seek small comforts to assuage the damage done by the world at large. We bind together as a takatāpui community to reaffirm our place in the world. There are many beautiful contemporary examples of this—one of my favourite is witnessing the revolution happening within the realm of tā moko.

As a revived art practice, tā moko is taking our people by storm. Naturally, the revival of moko kanohi is also lending itself to vital wānanga about the role of takatāpuitanga within our iwi and hapū and how those intersections are depicted in our visual languages. Moko is also an intergenerational story-telling tool, it provides us with examples of the roles our ancestors played in the world they lived in.

Through this visual language, we are given a medium by which to inherit the mātauranga of our tūpuna. This wānanga is happening amidst the evolution of an art form by practitioners who have worked for generations to revive their entire visual language—one that is based upon the reflection and reverence of our natural world (which includes our social structures) on the most visible of canvases—our skin.

All creative pursuits fit within the realm of storytelling—visual arts, writing and performance arts encompass the visions we have for the world we live in, come from and dream of. Even the āteanui o Te Matatini has been host to some incredible performers who proudly demonstrate their takatāpuitanga for all to behold. These performers embody the reclamation of both our contemporary and pre-colonial takatāpuitanga in a way that celebrates, normalises and demystifies the power of our very connected intersections.

When we tell stories of and as tangata takatāpui, the whāriki becomes rich beyond our wildest visions. Our storytelling abilities and the connections we can make between worlds are part of the way we use our pūrākau to reaffirm our place in the world. We are an integral part of the narrative told upon the whāriki to our children and we are an important part of the story of our ancestors—especially those that weave us back into its broken threads.

Part Three: The Threads of Our Mat are Strong

Oh my, mokopuna

How the world has changed for you! I hope you are liberated,

free from oppression, from colonial pain, from phobia of the love your tūpuna

shared between them, the love that created a bond from which you could bloom—

I hope I held the beasts upon my own back, and that these scars are caked in soil to rot— rather than have landed themselves upon your own fresh canvas.

Preceding our hekenga mai ki Aotearoa, we were part of the vast interconnectedness of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa. One of my favourite ways to imagine this time is to think of our ātua and the way they evolved as our sea-faring ancestors moved around the world. We were part of the biggest nation that has ever existed—our nationhood wasn’t defined by countries and continents. We were the people of the sea, who traversed the biggest body of water our planet has to offer.

Our atua moved with us. When we needed knowledge about growing food, we told stories about Rongo-mā-tāne. When we needed examples of conflict, we told stories about Tū-mata-uenga. When we found a rich, lush landscape with more trees than we could count, we gave Tāne-Māhuta prominence befitting such a space. We held history in our hands and wove it into our children’s lives, keeping them equipped with the knowledge that enabled us to survive for centuries.

Within te ao Māori, we have reintegrated and reformed our language to reflect the needs of our community —“Takatāpui is an umbrella term that embraces all Māori with diverse gender identities, sexualities and sex characteristics including whakawāhine, tangata ira tāne, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and queer. Takatāpui identity is related to whakapapa, mana, and inclusion. It emphasises Māori cultural and spiritual identity as equal to – or more important than – gender identity, sexuality or having diverse sex characteristics.”—Dr Elizabeth Kerekere.

We also know that practices within the takatāpui spectrum were commonplace across pre-Christianised Pacific. In Hawai’i, the term ‘aikāne’ (or ‘moe aikāne’) was used to describe the very public, very legitimised same sex relationships amongst nobility. It wasn’t just commonplace, it was encouraged. The term ‘mahū’ was used to describe members of the gender spectrum. All of these were normalised, all had a place in the world.

The revitalisation of the word takatāpui has brought about a more inclusive understanding of the term: “Those who were born with the wairua (spirit) of a gender different to the one they were assigned at birth may call themselves ‘irawhiti’ (with a gender that changes or is associated with change), ‘whakawāhine’ (creating or becoming a woman), ‘tangata ira tāne’ (a person with the spirit or gender of a man), or one of a number of other terms. The contemporary te reo Māori word for transgender people is ‘irawhiti’. This can be used by transgender women, transgender men, and those with non-binary genders. ‘Ira kore’ is the term used by those who don’t identify with any gender.”—Johanna Schmidt for Te Ara3

We were and are a vital part of our cultural community. Our ancestors moved regularly between Tahiti, Hawai’i and Aotearoa, sharing knowledge, building relationships and creating a sense of community that we emanate today. When I think about the world I want my mokopuna to know, it is this vast network I introduce them to—subtly, quietly, normally.

I do so by questioning the curiosities of my child and the children within our immediate whānau. When I see them fixate on an element of nature, I encourage them to think of the life force that made that element exist. I guide them towards the wider network of that entity —what plants does it look like? Where else can it grow? How does the wind move that? Why? That’s the mātauranga that has been given to me—the ability to question everything and dance with delight as my brain ponders all the possibilities!

Recently, this relentless curiosity was spent researching atua within an academic context. Part of that pursuit involved seeking the tikanga associated with different atua—how their relationships with each other dictated our relationships with them. This required copious amounts of observation, reading and writing.

Naturally, my observations of nature lead me to pursue the idea of queerness in atua.

We had been told by a guest lecturer4 that their personal view was that many of our atua were gender fluid. They gave the example of the ocean having such a prominent role in our world view and that, in a number of examples, the presence of gender binaries restricts the role of each atua to a form they don’t necessarily take. Could Tangaroa be a non-binary atua?

They challenged us to use the power of observation and research to find compelling evidence otherwise. We couldn’t do it one short afternoon. What we did find was further proof that our world became what it is because life creates life, the interconnectedness of all things leads to the evolution of life itself.

I spent a lot of time watching the water and pondering this. I would watch the waves lap against the sea and wonder, was that gentle caress Love? Did the ocean love the land—were they fighting where it’s rough, arguing over who left the milk on the bench / cuddling where it’s gentle, having a Netflix and chill moment through the sand? There are kōrero whakapapa from different iwi about potential relations between Papatūānuku and Tangaroa, which makes sense when you look at how the two interact.

For me, there began to be something kind of erotic about the lapping of waves against land. Something cunnilingual. One of our female atua who has had an historically abysmal record of academic attention is Hinemoana, the Goddess of the Deepest Sea, wife of Kiwa. Why couldn’t Hinemoana and Papatūānuku be lovers? Why can’t the pull of the tides be their perpetual love song—sending the deepest sea to meet the softest land? Were they lesbians? Could they be gender-diverse? Could two entities of the sea (Tangaroa and Hinemoana) be one and the same, separated to appease the missionaries and their pens?

Or perhaps Hinemoana and Papatūānuku / Tangaroa and Kiwa were all a big polyam-crew out there in the blue?

Could all these relationships that begat the world be proof that whakapapa has no gender?

I’m not questioning the existence of reproductive whakapapa as it pertains to our creation stories here. I’m questioning whether all manner of relationships exist across the spectrum of our atua and the interconnectedness of life itself and if they are richer when we decolonise our view point and re-indigenise our perspectives.

I’m asking how our mātauranga might evolve if we strip the colonial lens from our observations and seek visions of the world without binaries. What more might we learn of Hinemoana if we make sapphic her stories? How much broader does our understanding of the sea become, if Tangaroa is a non-binary boss of the biggest mass on the planet?

The answer is unequivocally, yes. It does change our understanding of what we observe. Takatāpuitanga directly enriches our ability to perceive the world as a better, more diverse petri-dish of evolution. Whakapapa is a spectrum, gender is a spectrum and love is the centre of all. It’s up to us to decipher the observations we make.

Which makes us an incredibly strong thread binding all of life together.

Part Four: Laying Down upon the Whāriki

Oh my mokopuna,

I hope the words of my kuia found their way into your mouths,

I hope I spoke them, wrote them, behaved them into your potential—

let me download them to you in this pūrongo loudly so that you may grow knowing exactly who the fuck you are—how you are loved beyond lifetimes, how we wail for you

how we long for you, how we laugh when you laugh how we joy when you joy

how we live, we live! My moko, we live

in you.

As a whakapapa-obsessed adult, I have spent years harvesting information pertaining to the names and dates associated with the biomes who made me. This journey led to the discovery of new and exciting characteristics I had often suppressed being welcomed back into my life.

I frequently think of how different it will be for our mokopuna. For the first two decades of my life, I was certain of only one thing—becoming a mother. By some crazy circumstance, I became pregnant at 21 years old. Unfortunately, I was also informed that I wouldn’t be able to naturally birth any more children.

As a young, single, queer mother, my period of grief about this was . . . odd. Fifteen years and copious amounts of therapy later, I understand now more than ever that I had disassociated myself from this reality. Prior to this, I had been a kid with two life-long dreams: to be a writer and to be a Mum. I wanted a minimum of seven kids and a giant brood of cousins, to foster as many tamariki and rangatahi as I legally could and build a home that nourished, uplifted and felt safe for all who entered. I wanted to be my own hapū, to be so secure in the company of my whakapapa that I could fill my world with it.

But life doesn’t work that way. I find myself now on the cusp of perimenopause, hormonally grieving the babies who never were. I am also now a full-time caregiver parent, navigating the world of disability advocacy and accessibility challenges against a world set on exclusion. And though it seems a million years away from where I am today, I am welcoming in the mokopuna to come. I talk of them daily, I write to them, I fill my house with their one-day-parents and I teach this generation of new little loves all that I can about being warm and fed and kind.

I seek every morsel of whakapapa knowledge that I can so that, when they ask, I have stories at hand to validate their existence in our world. I want them to live so joyfully that the pain my parents, grandparents and everyone in between experienced can be nothing but sad songs they lament to remind them of the world that was.

Finding myself has meant getting real about what my journey as a mother, nanny and ancestor will actually look like. I can’t physically produce any more children. But I will raise them. And that’s the song my heart is filled with.

I want to acknowledge how rare it is that, in my whānau, queerness has never been a barrier to the raising of children. When asked about my visions for having more descendants, I have often replied that I am someone with a lot of love to give. Many of us are, and the world we live in often suppresses and manipulates that love to seem like something less deserving of the beauty that it is.

I will grow old sharing the love I have been given with every uri of every member of our whānau. I don’t care how they come to us, just as our kuia didn’t care how we came to her. There are too few whānau where love overrides all prejudice for us to break that chain and stop welcoming lost little hearts into our privileged world.

A few years ago, I met someone who finally melted my big icy heart into a relentless tide of love. Together, my teammate and I are building a foundation upon which our moko will flourish. We are polar opposites: introvert / extrovert, cook / cleaner, curly / fine, up the guts / round the long way, te mea, te mea. They have perfectly complemented my burgeoning nanny-tanga, and given my whāriki a strength I didn’t know it lacked.

When my beloved stands to speak, I provide waiata. When I pao, they stand solid. When we facilitate events, we are two pou holding both sides of the whare. The strengths we each bring to the whare are unique to us, and we work to find the complementary threads that bind us together. Stronger, we demonstrate the tikanga we have learned.

Their experience has been quite different to mine and that negotiation has meant that I have to adjust my rosy lunettes to view the reality of theirs. Sometimes, life just works out that way. You find the people you find, when you’re supposed to find them.

Our moko will come to us in the same way, and when they ask why we chose them—I will talk about my nannies and the way they loved through life’s harshest moments. I will show them where our atua live and ask them what they see. I will share with them moments of my life and the way it taught me the truth about love. I will sing them oriori I learned off YouTube and read books my friends wrote and say karakia my child has taught me from kura.

I will sit them down upon our whāriki and tell them:

Love is the name of our whāriki. It is made up of all the threads of our whakapapa and upon this whāriki, we are the present, the future and the past.

E ngā tūpuna ē

ānei taku karanga atu ki a koutou,

he karanga aroha, he karanga manawanui.

Moe mai rā ki te whāriki nei,

te whāriki aroha.

- Creation traditions or narratives that explain the evolution of our natural world, and vary from rohe to rohe. ↩︎

- Although often translated as ‘god’ this is a misconception of the real meaning. The term atua essentially refers to the life force of the many elements of our environment (wind, rain, land, sea, rock etc) personified through supernatural beings. Our kōrero atua describe the relationship between these elements, and the evolution of our natural world. ↩︎

- Johanna Schmidt, ‘Gender diversity – Māori and Pasifika gender identities’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/gender-diversity/page-4 ↩︎

- Note that I’m being really careful about the origins of this kōrero here, this is to protect those who have shared with me these whakaaro. ↩︎

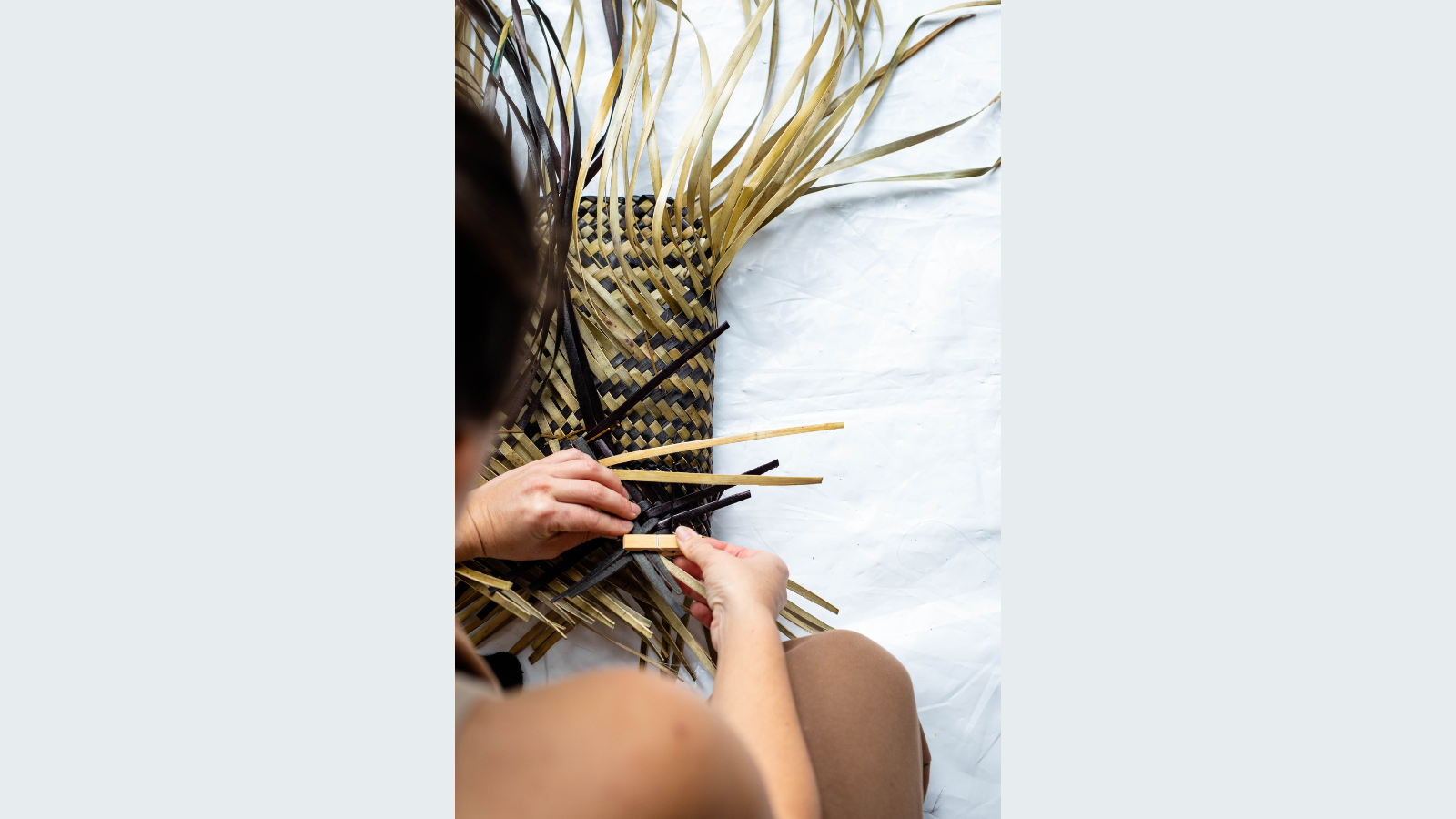

Featured photo by Trinity Thompson-Browne.

This work has been made possible thanks to financial support from Burnett Foundation Aoteaora.