Bird Child and Other Stories, the latest collection from esteemed author Patricia Grace, had me as hooked as fish to Māui’s rod. I consumed it in great heaving gulps, and though I expected no different from a writer of Grace’s calibre, I still found myself surprised by the number of times I finished a sentence, took a breath, and then took a photo on my phone to save the words for later, or perhaps forever. Bird Child and Other Stories takes us from the potential of te kore, to the growth of te pō, to the bright realisation of te ao mārama.

The way the generations shift across Bird Child and Other Stories is at once both mesmerising and in perfect keeping with a whakaaro Māori of the nature of time. The beginning section of the book tells the stories of our tīpuna and atua, those whose narratives are held as taonga within the breadth of our collective understandings, but whose lives we couldn’t pin down to a particular time or age.

Perhaps it’s the flexibility and openness of these pūrākau that allows us to utilise them time and time again; to reassert our tikanga, to remember where we come from, to remind ourselves what we’re made of. Through each of the stories in this chapter, Grace reimagines the classic stories of our old people, of Mahuika and Māui, but through a lens that offers us a new perspective on these otherwise well-known tales.

What if Rona could see what is happening to Papatūanuku at the hands of humans? What would she have to say to Moon? Where might Māui find the marbles that Sun lost when he ensnared him? What if we need all that light, after all? Grace has the ability to find and highlight the threads that bind together our oldest stories with our newest world, and seamlessly, walks us backwards into the future. Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua.

“Had Sky been too distant? Had Earth been too compensating? What could they have done about it anyway? Was it all a question of light?”

‘Sun’s Marbles’, p.85

This is not where this story ends, but the sentiment remains—people, ancestors, whānau—they are at the heart of what it means to be Māori. The connections that bind us together are the basis upon which our lives are formed, and this concept is hammered home throughout each story, regardless of which connection Grace is focused on in each tale. In some parts, the connection between people and our environment seems to be the relationship that Grace most urgently wants to comment on, urging us to rethink our pūrākau in the context of a world that is hurting.

The world, too, is written into life as a living being, always capitalised, strong in the animism that many, if not all, Indigenous cultures share. At other times, the author comments on the mauri shared by all living beings, irrespective of type, as is so memorably demonstrated in the union of a child and a bird in the titular story. In other sections, it seems that Grace’s key message, although always artfully buried within poetic prose and flashes of te reo Māori, is that the parallels we share as tāngata Māori should always be used to bring us closer together, rather than further apart.

“If you do not have a people, you cannot be a person.”

‘Bird Child’ p.57

As ever, with Bird Child and Other Stories, Patricia Grace has solidified her place as one of Aotearoa’s greatest writers by providing us with yet another work of pristine skill, and heartful narratives. This book is important and should be embraced as a significant pou in the realm of Māori literature. Rangatahi should read this book to find out where they come from. Kaumatua should read this book to remember how far we have come. Everyone should read this book, to see how bright the places we’re going could be.

Yes, āe—it is all a question of light.

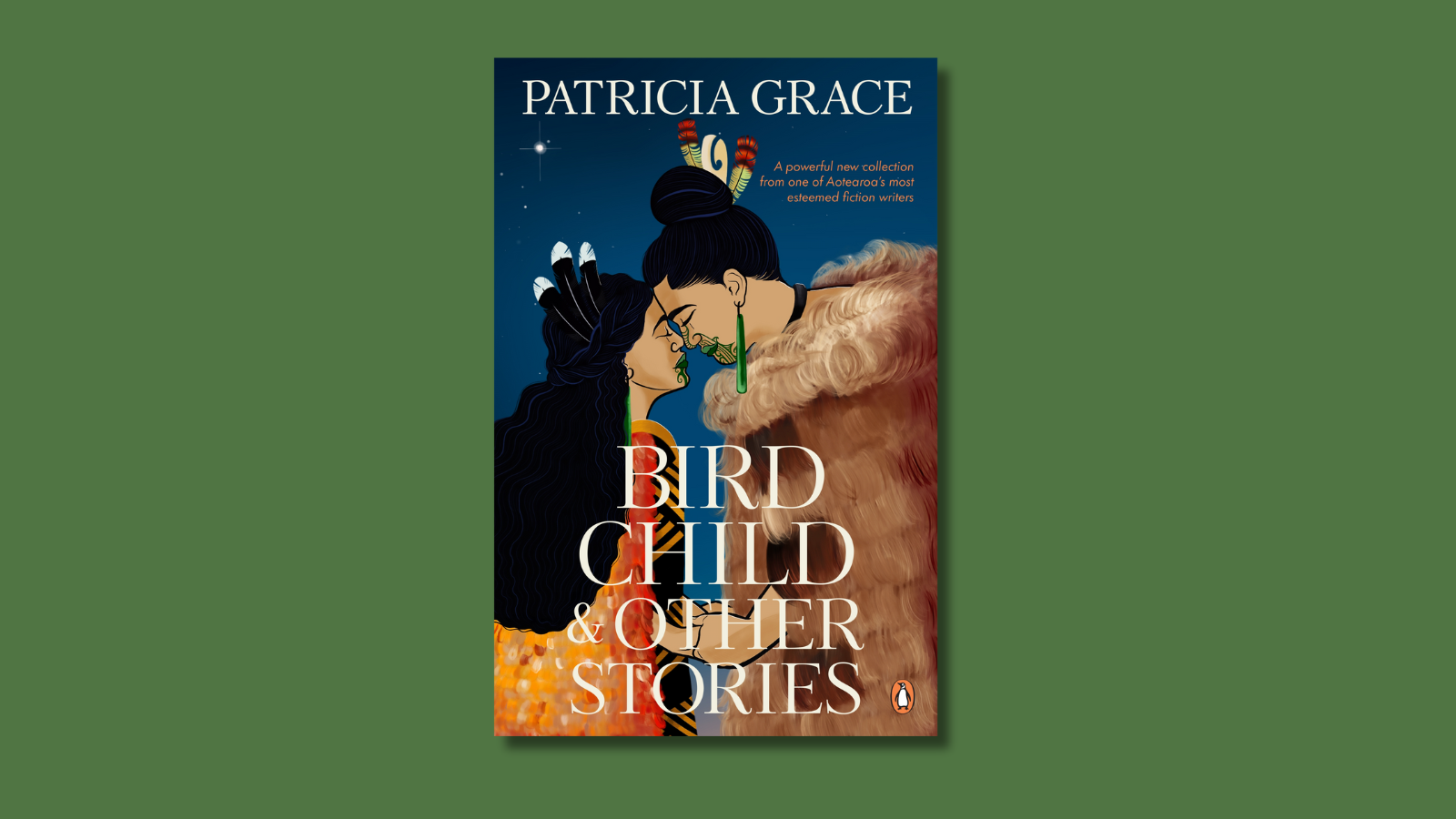

Featured image courtesy of Penguin Random House NZ.