Spoilers ahead! This review will discuss elements of the book that could be considered spoilers. You have been warned.

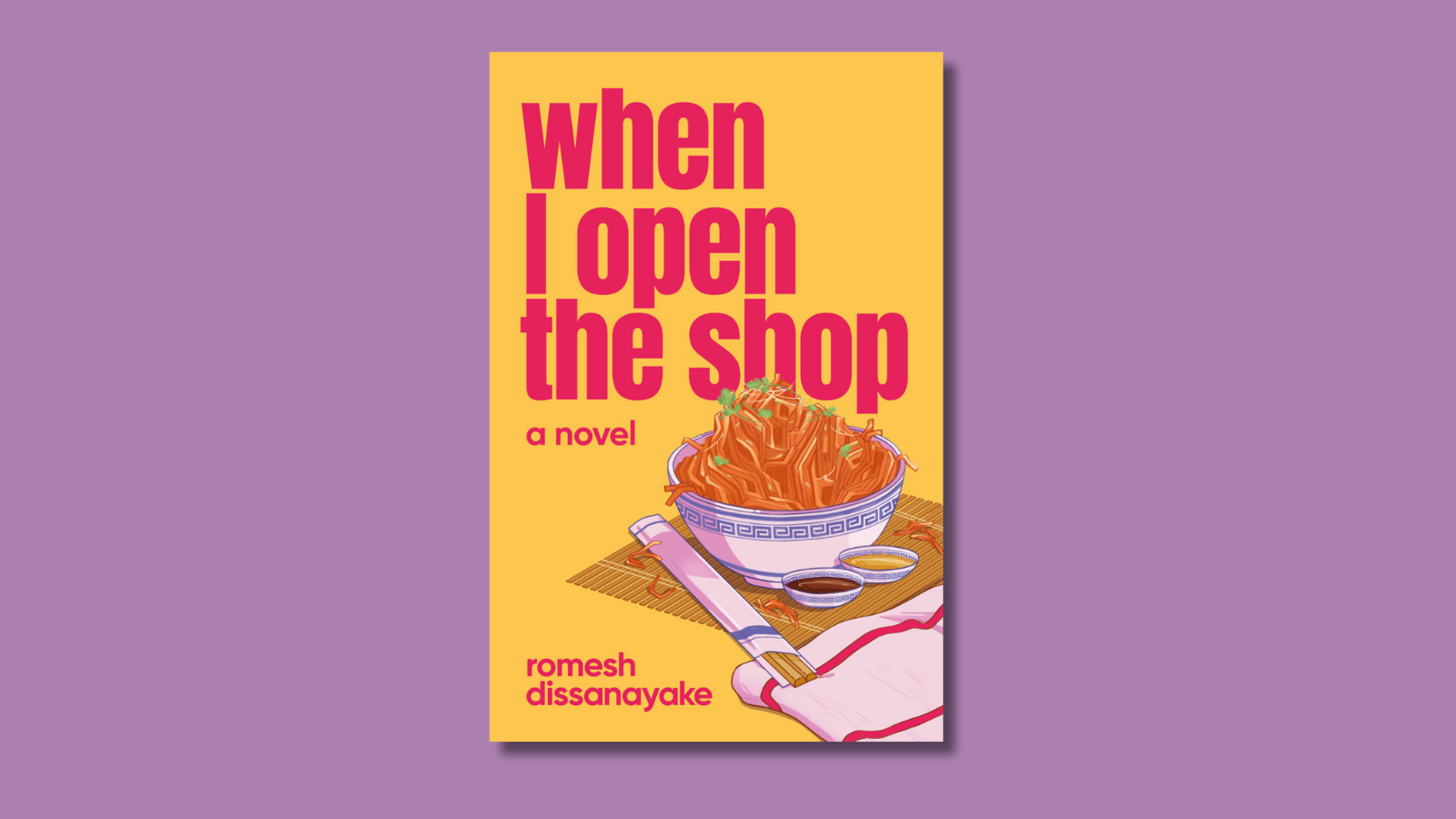

There is an often-unspoken knowledge that people of colour share. It is, ultimately, a kind of knowing beyond words, an embodied wisdom, a comfort in contradiction, a transcendence/ing of fixed binaries. In his debut novel, When I open the shop, romesh dissanayake stares down one aspect of this kind of knowing—that it is both a burden and privilege to relate to the question “Where are you from?”

The story begins with an unnamed narrator whose mother has died. Five or six months have passed and he has spent the summer consumed with funeral arrangements and the work of starting up a noodle shop in Te-Whanganui-a-Tara. There, he wades through mundane, logistical tasks that allow him to sell a kind of appropriately watered-down version of his family recipes to Wellingtonians.

Early on in the story, in the middle of his grief, our narrator is confronted in his noodle shop by an older white male customer who is drunk and only interested in telling the sad and violent story of his life. He breaks momentarily from his monologue to ask the narrator one question. The question “Where are you from?”

When the question is raised and directed at the narrator this early in the book, I feel the classic frustration—Why, whenever a person of colour writes a book, do we always have to be pinned down? Why does the axis around which we—and our creations—turn have to be this question? This blunted essentialism imposed by whiteness? It’s a question that in this instance is not seeking an answer, but an explanation.

dissanayake does the wonderful thing; he has the narrator lie. This sidestep is a skilful narrative development. For the reader who has been on the other side of this question, it is a relief. For the unknowing reader, it is an instruction. This story is not an explanation. It’s a story. What’s given will be given in its own time. What’s given is a gift.

And much of When I open the shop is a gift. It has the feeling of embodiment to it—not the general embodiment of life, but the specific embodiment of this person, this narrator, who moves through the world in their particular way, with their particular history—which we are delivered glimpses of throughout the book. The story is most of the time, highly uninterested in ‘explaining’ itself. At times, painfully so—much of the first half of the book feels like an act of delay. We are waiting for the ‘flood’ of emotions to come out, the ‘grief’. But instead, all we get is the mundanity of life.

This is a story in touch with grief. I hesitate to write this because I don’t want it to come across as reductive. Grief feels like a label that can be slapped onto a story and become defining. dissanayake works to reject and subvert this understanding; he depicts grief not as reductive, but all-encompassing. It’s one of those life emotions that is so big it’s bigger than itself. It touches everything—not necessarily meaning everything is sad but that everything is different. Grief changes the experience of time, which is the experience of life itself.

“Grief feels like a label that can be slapped onto a story and become defining. dissanayake works to reject and subvert this understanding; he depicts grief not as reductive, but all-encompassing.”

The malleability of time through grief (contemporary and ancestral) is explored through the structure of the book. When I open the shop is a novel in three parts. dissanayake adopts and subverts this classic structure skillfully. He plays with narrative escalation and ideas of chronology—refusing to conform to certain expectations—what if we jumped into the future with little explanation? What if we jumped so far into something else we weren’t sure if it was the future or the past or a different world, altogether? This is a story that will be told in its own time, at its own pace.

This feeling is present from the first chapter—time blurs, and the future bumps into the present and the past from unexpected angles. Grief is represented as not necessarily devastating, but dulling. It pulls everything into a kind of sameness. It’s frustrating. But that’s not all there is. Dispersing the periods of time-numbing grief there are moments of blinding salience. Lying in the grass after an alienating one-night stand and watching the sun come up. Or, perhaps, being struck with the realisation that if you could set everything to flames, you would. This is what our narrator tells us at the end of the first chapter:

If I could. Do it all over again. I’d set fire to that apartment, claim insurance and be done with it all.

If I could, I’d set up a camping chair outside and drink tea and watch as the memories of my mother,

the funeral, and the summer all went up in flames. If I could, I’d burn all those antihistamine

packets, those toilet paper rolls, those letters from the hospice and watch them billow up in the air

and come down like snow.

I’d watch them all get swept by the wind.

I’d sit back as they dissolved, like salt back into the harbour.

Salt is a recurring image that becomes particularly arresting in the second section. The narrator is on a road trip with his employee, a young man he struggles to connect with. They drive over the Remutaka Ranges in the middle of a storm. The mundanity of grief is oppressive, and it all just keeps going until it accumulates, in a stunning moment of horror that marks a significant transition in the story. A threshold is crossed.

It is after this that the book transforms again. It breaks from prose into poetic form—a series of numbered poems under the title THE ISLAND. We follow the tight narrative of Manone and Mantoo, two people who appear to live alone on an unnamed island. They collect salt from the ocean and dry it in the sun and fortify themselves against an oncoming storm that lasts for a month.

This section is sparse but rich in its imagery and narrative, feeling almost like a fable or myth at times. dissanayake is skilled at the poetic form and the numbered sections pass with a breathless, mesmerising quality. The story of Manone and Mantoo is conveyed but it feels different, like it is registering in a different part of the body. It’s a skilful act and it’s hard not to think that Mantoo and Manone are ancestors of the narrator, though the connection is never made explicit.

“dissanayake is skilled at the poetic form and the numbered sections pass with a breathless, mesmerising quality.”

The unexplicit nature of THE ISLAND injects depth and mystery into the story but perhaps mystery is the wrong word because its purpose is not, I don’t think, to be speculated on by readers or ‘solved’. Once again, the story is not interested in explaining things on anyone else’s terms. If there is any mystery, it’s the mystery of every day, the ways that we often don’t—can’t—know the histories and stories of the people around us—how rich and deep all of our ancestries are. In this sense, there is no mystery and if there is one it belongs to the narrator and the communities in this story, not the outside reader.

Outside their shelter he sees

the last rays of the day

refracted through,

a pillar, a person,

an obelisk.

A glistening, glorious

tower of salt.

The story evolves again in the third section, where the introduction of many more characters creates a different tone and pace. We jump forward in time and meet our narrator again, years later. This time, he has a partner, friends that we meet in the present (not just spectres of the past). His shop is popular and successful. His life is rich with chatter and the bubbling pleasure of food shared with those who you know and know you in return. Love and care ooze from the pages. We see the narrator’s community and it is here that we learn his name. In a kind of backwards walk out of grief, we see that Devendra has unburdened himself of the momentary alienation of sorrow.

It’s impressive—how this section of the book, in its aliveness, throws the earlier sections into stark relief. There’s a catharsis in realising that Devendra was moving through the world in a particular way—painful in its heaviness and necessary, of course, but not final. Things change. We can move from moments of horror to moments of joy and dissanayake bravely depicts this transition on the page. Pausing at the invocation of bravery—why does it sometimes feel so ambitious for artists to depict hope and happiness? Perhaps because hope is so urgent—necessary, and real but also complicated and ongoing. It’s a challenge to make it believable—not because people are cynical, but because hope is more complicated than anything that is fixed and more meaningful and energised than any platitude. Hope is alive.

While the ending of this story, at certain moments, feels simplistic (the dialogue between him and his father comes a little too quickly and cleanly for me) ultimately I am left believing in the kind of hope dissanayake depicts. This is the kind of hope that exists in our complicated relationships, In our communities, between people.

It is wonderful to read the final scenes where Devendra and his partner Nishanthi host their friends for dinner. They are effortless moments and even more impactful because we understand what came before—the darkness of riding through the night, in a storm that has no clear ending in sight. We can see, now, that Devendra has landed somewhere. Not in a place without grief but simply a place that is bigger, messier. A place where there is room for laughter. For things to keep going. For more.

You can purchase When I open the shop from your local bookseller, from BookHub, or directly from Te Herenga Waka University Press.

Featured image by H Y Chai courtesy of Te Herenga Waka University Press.