Plastic, Stacey Teague’s latest poetry collection, is a heady mouthful of exactly-what-the-doctor-ordered. I consumed it in one gulp during my lunch break at work. It took me straight out of my office where I work as a high school dean and kaiako reo Māori, and put me right back into my body. When I finished the final poem, I realised that I’d been both holding my breath and nodding along to Teague’s kupu as I read, so familiar as her tales were to my own experiences. Every page brought a new sense of “Me too!” or a nostalgia for a world that I too have known. Evoked through her illustrative phrases, and the weighty contexts they contain, was the experience of being seen and understood by a writer, and the feeling that I too was seeing and understanding them.

Takatāpuitanga is a key theme throughout Plastic and is an element of it that instantly drew my attention as a reader. Though queer, Māori writing has existed for as long as all writing has, Plastic highlights a specific experience of takatāpuitanga that is relevant to the modern day, and feels like something that will be remembered in the future as a pou that we can cherish. In so artfully displaying this takatāpui identity, Teague offers her readers a chance to feel like their own selfhood is being realised in front of them, especially for rangatahi who might not often come by media that reflects them back to themselves like a mirror. Though Teague’s writing is simply a documentation of her experiences, it also holds the power of highlighting the mātauranga of te ao Māori which would tell us, like Teague is, that our identities and sexualities are acceptable and treasured in all forms.

“and I do want a little forehead kiss in line at a medium-tier rural cafe I will eat a huge slice of lolly cake you will drink a huge chocolate milkshake everything will be just huge” (blue hours, pg. 30)

However, it’s not only the takatāpuitanga in Plastic that makes the collection so distinctive, but the overarching focus on relationships and people as a whole. Strung throughout the poems is a sense of whanaungatanga that seeps from the titles, to the poems themselves, and into the many dedications Teague offers to the authors of works she has been influenced by. In this way, the book itself feels like it is part of a wider whakapapa, and that Teague is situating it within the greater web of that which has come before, and that which is yet to come. The way in which whānau feature as the focal point of many of the works adds to the feeling of connectedness that this pukapuka provided me as the reader, and speaks to how those who surround us add their mauri into our own narratives time and time again.

“my narn sang waiata with her guitar until her voice stopped and her guitar was replaced with a dialysis machine” (Kewpie, pg. 79)

Just as whanaungatanga is accentuated throughout Plastic, so too are all aspects of te ao Māori, and in particular, the experience of reconnecting to the culture as an adult. Reclamation of one’s roots, especially in the context of Māori in the twenty-first century, is not only ‘hot topic’ but also a collective plight shared by so many in modern-day Aotearoa. Teague’s ability to capture both the heartache and the homecoming that come from this journey speaks to the efforts of thousands as we aim to recover what was lost to the generations before us.

“Teague’s ability to capture both the heartache and the homecoming that come from this journey speaks to the efforts of thousands as we aim to recover what was lost to the generations before us.”

Through raw language, Teague gives us an insight into her own experiences of going to her marae for the first time, and being corrected on her pronunciation of kupu Māori; but in doing so, validates our own experiences in similar situations. There is a familiarity to the ways in which the author talks about te ahurea Māori throughout the book, switching from the kaupapa of language revitalisation to her hair colour, from her mother being dubbed ‘Ngāti Plastic’ to a whole chapter dedicated to atua and tīpuna wāhine. This is a book of mātauranga, of recovery, and of mana.

“to make white is to bend down to islands of shame” (whaka—, pg. 28)

Overwhelmingly, Plastic reads as an ode to the people, places, and taonga tuku iho that Teague references, and as a mihi to both the past and to the future. The chapters of ‘spells’ throughout the collection speak to the latter, small and digestible pieces—though innately poetic and authentic—they themselves up as koha, or as karakia, to those who need it. The myriad features of ancestors and atua speak to the former and honour the ones who paved the way for Teague’s refastening to the Māori world. There is no doubt that in reading this collection, like me, they too would be thankful to their mokopuna for telling the truth, sharing her journey, and managing to do it with such lyricism. Plastic is a must-read for all. Prepare to be nourished, changed, and unable to put it down.

You can purchase Plastic from your local bookseller, from BookHub, or directly from Te Herenga Waka University Press.

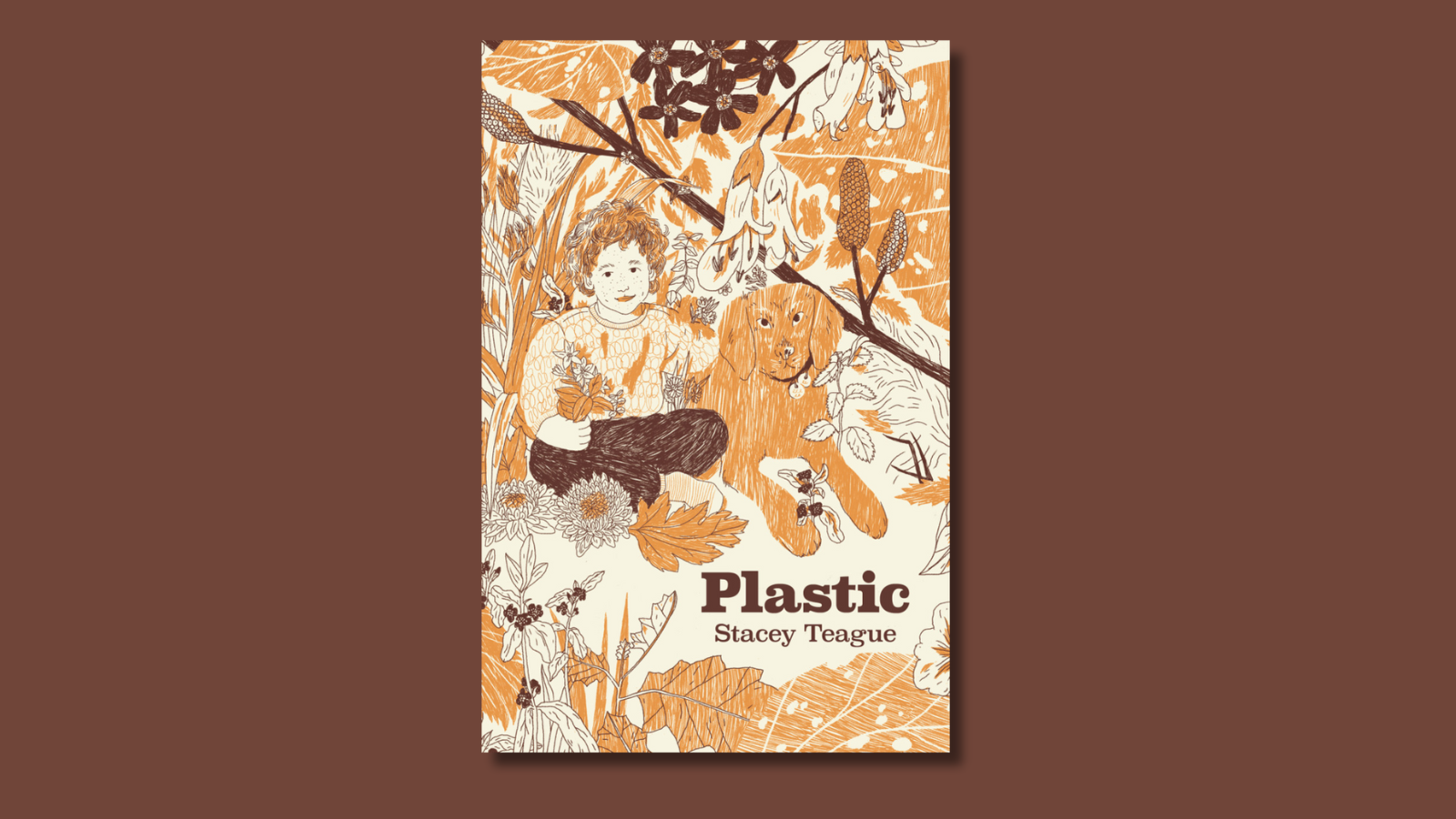

Featured image by Sarah McNeil via Te Herenga Waka University Press.