I don’t know how to write about being Chinese. Whenever I shared my whakapapa as a kid, I would say ‘Malaysian-Chinese’ because that’s the truth. While I was born in Aotearoa, I had always put ‘Malaysian’ before ‘Chinese’ because I’d been to the so-called ‘Gateway to Asia’ countless times, but never on the soil of my Hakka ancestors. My disconnection to my roots ebbs and flows, and so does my willingness to connect with them.

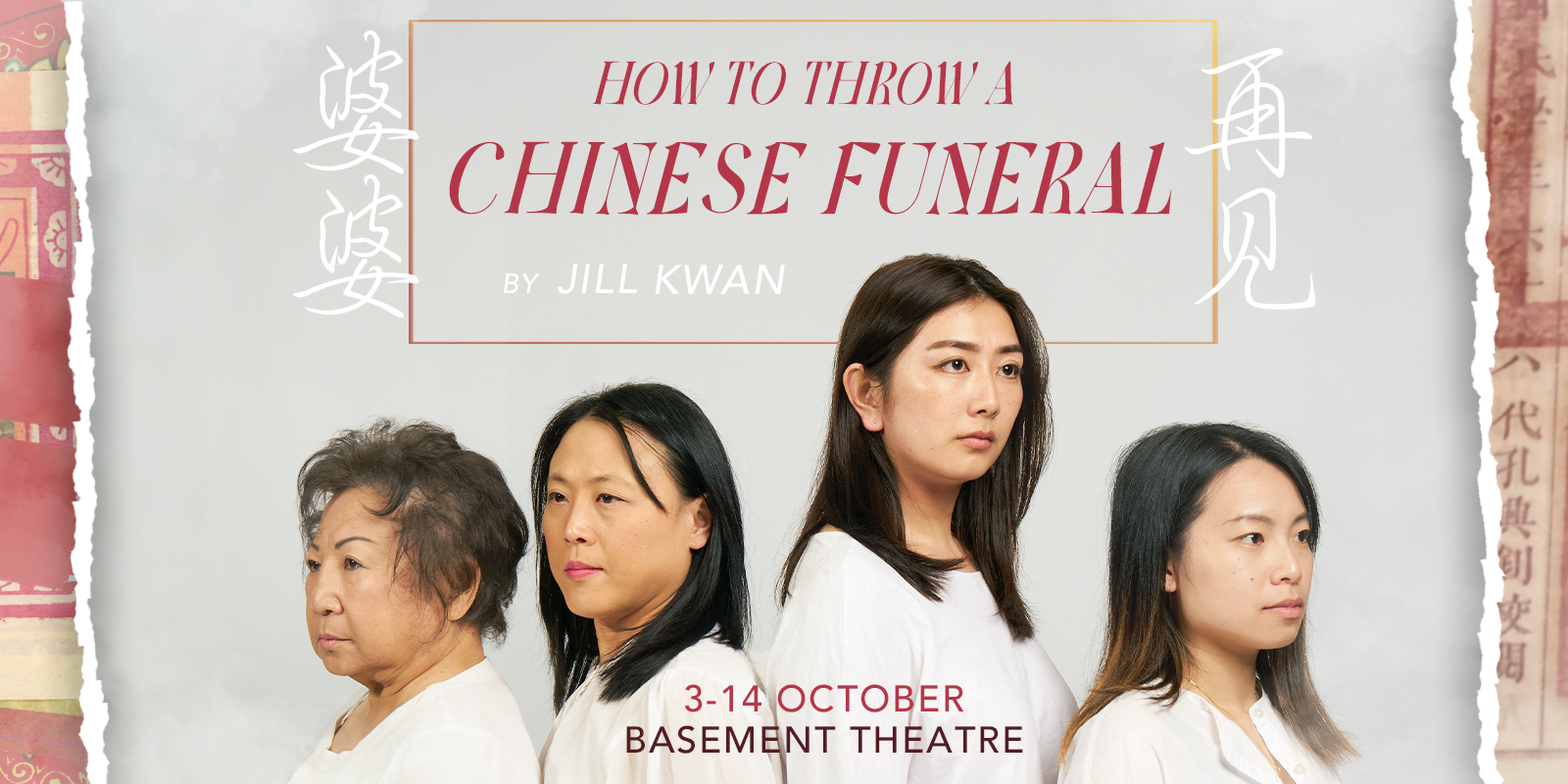

It’s 2023 and I’ve just sat down to watch Ji Lian Jill Kwan’s play How To Throw A Chinese Funeral 婆婆再⻅ (How to Throw) at Tāmaki’s Basement Theatre. This co-production by Proudly Asian Theatre (PAT) and Hand Pulled Collective (HPC) centres upon a Chinese-Malaysian family who must reconcile with each other and their Taoist tradition to send off their late matriarch. Set in timelines across Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh and Auckland, three generations of these Asian women grapple with familial roles and their culture as they grieve for Ming.

As a third-generation Chinese-Malaysian writer with ancestral roots in Guangzhou, Kwan poured her complex emotions and craft into the project she wrote and later directed. Just as tradition necessitates the striving for detail to achieve meaning, so too does this play. The key details in set design, music and lighting, character physicality, and puppetry transported me into the shoes of several Chinese immigrants, into timelines that span decades, and into cultural narratives that hold immense significance.

There is a clear need for Asian theatre—a deep thirst. Chye-Ling Huang (actress and co-founder of PAT) shared with me her insight into the conception and cultural meaning of the play since its first Fresh Off The Page reading (a free play reading development initiative by PAT) in 2020 and the successful Boosted campaign that funded its staging.

The set mimics a typical Chinese-Malaysian home, with Chinese decor and a Taoist altar. Chinese characters are embroidered onto the tapestry that makes up the walls of the home. How To Throw already stands out from other theatre pieces in this way, but also from Asian pieces.

“[HTTACF is] the first play that I’ve seen that’s been set in Malaysia, in Kuala Lumpur. A lot of works that talk about the diaspora aren’t set in the country of origin,” Huang says.

One of the first things we notice isn’t just the set, however, but the smell. Wafting through the space are the fragrances of Chinese herbs and an Asian home. Scent designer Rae Longshaw-Park has curated a sensory experience that evokes nostalgia—something that grief and all kinds of distance are unable to resist. Although it’s hard for me to pinpoint the exact sources of the fragrances, it ushers me toward a visceral recognition of my upbringing. Some things feel familiar yet foreign.

When the children Lily (Lisa Zhang) and Anna (Ann An) arrive at the funeral from New Zealand to meet their mother Mei and aunt Yi in Malaysia, immediately recognisable dialogue like ”Your shoes!” and “Ai yo, twenty-four herbs but I only taste one flavour—so bitter!” quickly introduce their divide from their culture. This catches quick laughs from the audience.

“The show has become more layered in terms of how the subject matter of grief and family disconnection can be surprisingly funny,” Huang notes.

Because sometimes, generational divides are just amusing and not all-consuming. There wasn’t a heaviness that sparked a self-pitying narrative that some Asian projects have leaned into. Instead, a suitable grief webbed itself onto the family as they were weighed down by roles handed down to them by people striving to do more than just survive.

“It always comes back to the heart of the characters and how they fight with and love each other.”

The play explores this tension between immigrant and traditional values noticeably through movement. I was captivated by the simplicity of certain individual movement sequences, such as when Mei’s historic moments are condensed into seconds. Clear associations, like where actor Yoong Ru Heng strips a ring off her hand and clasps her hands together in prayer, hint at the socio-religious toil that led Mei to who she is today. While this struck me with its effectiveness, its small place in the overall plot left me wanting to know more details. Perhaps these snippets mirror how memory works fleetingly and superficially, especially in grief.

When the youngest granddaughter, Anna, becomes pregnant, her mother cannot fathom what has happened to her. Her anger and assumption fall on the eldest Lily, who naturally assumes a protective sibling role and lets her mother believe this to be true. Anna An convincingly portrays a young girl who is assumed to be innocent and unproblematic. Her more timid or distressed body language is a strength onstage, where her character’s reactions (usually missed by her family) are always clear. For the youngest to be so overlooked, the shock that comes with her maternity reverberates through the family.

For Lily, her professional ambition as an entrepreneur is threatened from every side, as the eldest is expected to take care of any ailing parent, like her ill mother. Lisa Zhang expertly portrays Lily’s struggles for independence and her desire to protect her family. With effortless control, Zhang embodies an older sister whose own degree of westernisation is not seen as a shortcoming, but a matter of fact.

“Now, the diaspora children are thinking, ‘What role am I supposed to occupy? Am I supposed to be the independent spirit that makes my parents proud by embracing a foreign culture as my own or revert back to fulfilling a tradition that I don’t necessarily adhere to or know?’”

In taking the role of Lily, Zhang subsequently realised how some Asian feelings aren’t always so unique.

“The shared experience and takeaway is that as much as it feels lonely in these experiences sometimes, I realised I am not alone in the emotions and troubles that came up during the play.”

Even Kwan felt ‘foreign in a place that you used to not feel foreign’ during her visits to Malaysia. How To Throw focuses on the roles the characters take as Chinese women. The way each generation feels pressure to be faithful daughters, diehard sisters and careful mothers was masterfully spread through tension, built through opposing contemporary and traditional practices—of individualism and collectivism. Janet Tan plays the all too familiar and lovable Malaysian aunt Yi who takes pride in her filial duty and butts heads with Mei. As Ming’s eldest daughter, her ties to ritual and order overarch her sense of individuality. When finally asked what she would do with a load of money, she unsurprisingly has no idea.

The union of music and lighting was powerful. Only a mystery presence at Ming’s funeral at first, Lishanth touches a tender spot for us as he becomes poised in a one-sided dance with the shadow of his late ex-lover. Music from their time convenes with her playful shadow and the joyful memory of her voice. Mustaq Missouri’s physicality as an elderly man is utterly convincing, as is his character’s protectiveness over the descendants of his long-lost love.

“This production has elements of the surreal and otherworldly…It’s not entirely naturalistic, it’s a blend.”

The most visually and emotionally profound device that lingered in my mind was the use of Malay-Chinese shadow puppetry. In the same way that smell located us within the setting of the family home, the visual puppetry emboldened the soundscape with voiceovers of Ming and past snippets of the family events to seize our heartstrings in a cleverly traditional way. A ‘suspension of judgement’ that Huang characterises as a theatrical advantage for empathy.

“It’s really hard to judge a puppet in the same way that you can judge a human or actor.”

Voice actors Enchante Chang, Hweiling Ow and Tess Liew further animate the shadows and locate us within the timeline. Their emotionally rich voiceovers certainly felt ethereal against the projection backdrop, reaching new heights in how to retell narratives.

PAT is finally celebrating ten years of producing original theatre that bridges and makes possible Asian works to the wider community, charming audiences as much as enlightening them on the Asian experience. HPC fits like another finger on this glove, as its founders Talia Pua and Natalya Mandich-Dohnt stand steadfast in bringing lesser-known stories to the spotlight. For some of the cast, Lisa Zhang and Yoong Ru Heng expressed to Stuff’s Eda Tang how “safe” the rehearsal room felt to “explore and reaffirm their sense of cultural identity.” Huang responds that theatre does this for both Asian actors and audiences because of the proximity and immediacy that the stage affords.

”One of the most powerful things we can do is reflect that in a theatrical space because it’s fiction, but yet it’s real people standing in front of you enacting a life in which you can’t ever truly see yourself living…It helps us to feel validated and less alone. Which is nice. [Laughs].”

The inclusion of Charles Chan as a Buddhist monk brought a sense of authenticity to the funeral and an easy way to project the characters’ varying ignorance of his teachings. As the children bow incorrectly and fumble with absorbing his Cantonese, it’s clear that the importance of the ceremony goes a bit over their heads at first. Lily trips and crashes into the altar in a moment that felt a bit melodramatic but was effective nonetheless. However, by the time the family bid Ming a final farewell, no amount of cultural disconnection held back the bond each member had to their matriarch. This set tastefully gave the family some privacy through a roll-down blind. Just as the puppets’ faceless shadows enabled us to emotionally connect more freely, the partition switches all perspectives: The characters become just like the forms we saw, now on the other side with their lost loved one. That is the power of tradition and family. Our judgment is suspended as we watch them grieve as a group.

I don’t know how to throw a Chinese funeral. I experienced the same confusion as I bowed and prayed over a few days for my late 家家 grandmother, who passed away shortly before our plane landed in Kuala Lumpur almost a decade ago. When my mother and I arrived at the house, we had to crawl to her on our hands and knees because we were ‘late’. It was humiliating on top of being traumatic, but hindsight eventually revealed that what I felt was shame for not understanding that lowering myself to the ground was not disgraceful, but the most respectful thing I could do in front of my family.

Perhaps, I do know how to write about being Chinese, because I’m just writing about myself. The characters, in all their tiered disconnections from tradition, knew how to throw a Chinese funeral after all—because they are Chinese. To me, it isn’t so much about whether I could understand the words I was chanting for my own grandmother, as it is about adhering to the ritual of coming together in meaningful ways that felt grounding as well as spiritual.

So, how much tradition should we strive to keep in our families then? Maybe as much as we want to.

Featured photos by John Rata courtesy of Hand Pulled Collective.