A moment for the history books: over the weekend of the 25th and 26th of March, an estimated 10,000 people stood together across the motu to show their support for trans communities and counter-protest the speaking tour of anti-trans campaigner Kellie-Jay Keen-Minshull (aka Posie Parker). In Tāmaki Makaurau, Keen-Minshull and her small band of poisonous supporters—which included members of far-right groups Voices for Freedom and the New Conservative Party—looked like a tiny island in Albert Park’s rotunda surrounded by a roaring ocean of counter-protestors, with queer hero Eli Rubashkyn’s successful souping of the fascist mouthpiece proving the final straw and sending Keen-Minshull scurrying onto the next flight home. In nearby Aotea Square, Destiny Church’s ever-venomous leader Brian Tamaki led a bigger anti-trans rally. The pro-trans counter-protestors bravely stood down the bristling Destiny crowd as Tamaki’s supporters turned to violence, shoving protestors, ripping and lighting pro-trans banners on fire. The next day, trans people and their allies took to the streets in Pōneke, Ōtautahi and Ōtepoti, their protest turned to celebration with Keen-Minshull halfway to England and local fascists presenting in much smaller numbers.

Undoubtedly a massive win for trans communities, missing in coverage of the weekend’s events has been the longer history of trans activism that led to this historic moment. In what follows, I want to sketch a very brief outline of some of the work which has preceded these incredible counter-protests, in an attempt to honour those whose strength we build on, whose resistance and activism has made our own lives possible today!

In an interview with historian Gareth Watkins in 2013, the late Georgina Beyer reflected on all the violence she faced as a sex worker and openly trans performer in the 1970s and 80s. She explained to Gareth:

It put the fire in my belly to stand up against injustice like that, because when I rationally thought about it, nothing was there to protect me. I couldn’t go and complain anywhere and have some restorative something happen here. And that’s just the way I felt; that there was no lever for me in society. And so if that’s me, how many others are having to detail with that kind of conundrum at some point? Probably heaps. So it began a sort of anchor: I’ve got every bloody right to be here, and I’ve got every right to be like everyone else as far as existing is concerned. Why the hell do I have to put up with this? (1)

The defiance that lights Georgina’s story characterises the histories of trans activism in Aotearoa. Trans people, especially trans women, and most especially Māori and Pasifika trans women, have always been leaders in resisting trans oppression. Sometimes that resistance has taken more official forms, such as the creation of organisations advocating for trans issues. Other times—perhaps most of the time—trans activism looked as ordinary and yet overwhelmingly powerful as the attitude of defiance that many trans sex workers like Georgina cultivated in the face of their oppression, the ability to hold one’s head high, stand proud and stand tall in the face of dehumanisation and violence every day on the street.

Georgina was part of a generation of trans women who benefitted from the care of an older generation of trans sex workers like Carmen Rupe and Chrissy Witoko. These two women established coffee lounges in Wellington as early as 1967, creating spaces for trans sex workers—and all queer and marginalised people, for that matter—to gather together, socialise, and even strategize. Chrissy’s latest venue, the Evergreen, was warmly remembered as a “safe haven,” and from 1984 a drop-in centre for sex workers and used by local lesbian and gay organisations for meetings. (2)

Community building is a vital form of activism, and it was pioneered by whakawāhine like Carmen and Chrissy. Certainly, trans communities have never been utopian—they are not exempt from in-fighting, nor from racism and classism. It is also important to understand the devastating effect of oppression on the mental health of trans communities, the number who struggled with addiction and suicide, to avoid creating romanticised and one-dimensional narratives of trans sex workers. On the other hand, we must recognise and uplift the stories of defiance that all too often get buried in a narrative of repression: this was a time when trans people were explicitly encouraged to isolate themselves from trans community in order to be “accepted” by society. Trans matriarch Dana de Milo explained in an interview with historian Caren Wilton how the hospital considering her for gender-affirming surgery informed her that if she wanted to live as a “normal” and “successful” woman, she would have to abandon her trans friends. She refused:

I said, that’s absolutely impossible. I can’t do that. They’re like my family. We’ve gone through thick and thin together, been beaten up together, all sorts of things. Spat on, thrown drinks at. All sorts of things you would think would never happen to a person, we’ve gone through together. How can you say I have to dump them? (3)

In 1972 Hedesthia, the first trans organisation on record in Aotearoa, was established in Lower Hutt and soon developed chapters across the country. Founder Christine Young hoped Hedesthia would help mitigate the isolation so many trans people felt. The group’s newsletter, Trans-Scribe, connected trans people in more remote areas and allowed members to share their stories and build up community knowledge. “I have made so many friends and best of all we are one big happy group,” Hedesthia member Josephine reflected in 1978, “when you have the understanding, love, and peace of mind that being among those of your own persuasion brings…LIFE IS WELL WORTH LIVING.” (4) Hedesthia’s leaders also did a lot of advocacy work, running educational seminars for various community groups and organisations as well as campaigning at their workplaces for the right to use the appropriate bathrooms. (5)

Trans people were active in the gay liberation movement from the moment it was introduced to Aotearoa in 1972, with trans sex workers like Sandy Gauntlett and Pindi Hurring pushing for the recognition of trans issues within the movement. Sandy was one of the first members of the Auckland Gay Liberation Front, and single-handedly founded and ran the Rotorua Gay Liberation Front when they moved there in 1973. Though the group did not last longer than a year, in that time Sandy corresponded with over 100 locals, helping queer people feel less alone and making sure that the wider public was aware that queer people truly were everywhere. Sandy’s favourite protest was a kiss-in held by Auckland Gay Liberation Front, where they remembered “suddenly diesel dykes started kissing the men, and the men starting kissing the trans, it was just hilarious! Everyone got freaked out!” (6)

In 1974 Pindi founded the Transsexuals and Transvestites Union as a sub-group of the Christchurch Gay Liberation Front. The Union sought to investigate trans oppression, focusing on “the problem of which toilet to use; legal name changes on passports etc; [and] difficulties experienced when buying clothes etc.” (7) In July that year, during Gay Pride Week, the Union organised the first protest on record for trans issues in Aotearoa, a sit-in outside public toilets in Christchurch highlighting the dangers trans people faced in accessing these public facilities. The only record of this sit-in is its brief mention in the pages of The Circle, a lesbian-feminist publication run by local lesbian activist group SHE. Later during Gay Pride Week, The Circle noted a “less heavy” event “drew enthusiastic participation,” as members of SHE, Christchurch Gay Liberation Front, and the Union came together to play a friendly soccer match. (8) Although there was certainly transphobia in the gay liberation and lesbian-feminist movements, this record proves that there were also relationships of solidarity, as cis allies stood with their trans comrades.

In 1977 Carmen Rupe famously ran for Mayor of Wellington, backed by Bob Jones who intended to use her to make a mockery of local politics. Though her campaign was indeed often dismissed as a joke, Carmen genuinely believed in what she stood for. Decades ahead of her time, Carmen proposed the decriminalisation of abortion, prostitution, and homosexuality. She explained clearly in interviews that legalising brothels would help reduce violence towards sex workers, and that requiring regular medical checks would only make sex work safer. Her visibility was fundamentally important to the generations that followed her. Trans activist and community liaison for the New Zealand Prostitutes Collective (NZPC) Chanel Hati recalled seeing Carmen on television for the first time when she was a teenager, and how impactful it was to witness Carmen’s courage: “this trans woman got out there, with her big titties out, not shy…she broke down the barriers of conservative ideals about what being trans, or being gay, or being anything other than the norm is…we stand on her shoulders.” (9)

There are so many more histories of trans activism that could be shared. I could write more about Chanel, for example, who was one of the earliest members of the NZPC when it was founded in 1987 and who continues to fight for better conditions for all sex workers. I would need many more words to do justice to the stories of advocacy groups like Transcare and Agender NZ, to cover events like

Georgina Beyer’s political career or the founding of No Pride in Prisons, and to honour the life’s work of pioneers like Dana de Milo and Pindi Hurring.

Eli Rubashkyn’s brave “juicing” of Keen-Minshull at the Auckland rally on Saturday might be compared to the Queer Avengers glitter-bombing Germaine Greer for her transphobia in 2012, while the confrontations between Auckland activists and the Destiny Church/Vision NZ group are now part of the legacy of Georgina Beyer’s heroic confrontation with Destiny’s “Enough is Enough” marchers in 2004. The pro-trans rallies in Tāmaki Makaurau, Pōneke, Ōtautahi and Ōtepoti have undoubtedly made history, but they are not isolated events: they are now part of a proud history alongside so many other kiss-ins, sit-ins, pickets and protests led by trans activists. Not only have trans people always been here – trans people have always been fighting. And as long as liberation is on the horizon, the trans struggle lives on.

Get souped, fascists!

Reference notes:

(1) Georgina Beyer, Georgina Beyer, interview by Gareth Watkins, January 27, 2013, PrideNZ.com, http://www.pridenz.com/rainbow_politicians_georgina_beyer_profile.html.

(2) Renée Paul, interview by Will Hansen, June 13, 2019.

(3) Caren Wilton, My Body, My Business: New Zealand Sex Workers in an Era of Change (Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press, 2018), 191.

(4) Josephine, “The Other Side of Midnight,” Trans-Scribe, July 1978, 4.

(5) Will Hansen, “‘Every Bloody Right To Be Here’: Trans Resistance in Aotearoa New Zealand, 1967-1989” (Master of Arts, Victoria University of Wellington, 2020), 72–76.

(6) Sandy Gauntlett, interview by Will Hansen, May 10, 2022.

(7) Pindi Hurring, “Drag Queens, Transvestites, Trans-Sexuals,” Newsletter: Gay Liberation Front Christchurch, February 1974, 4.

(8) “Gay Pride,” The Circle: A Lesbian-Feminist Publication, July 1974, 1.

(9) Chanel Hati, interview by Will Hansen, June 13, 2019.

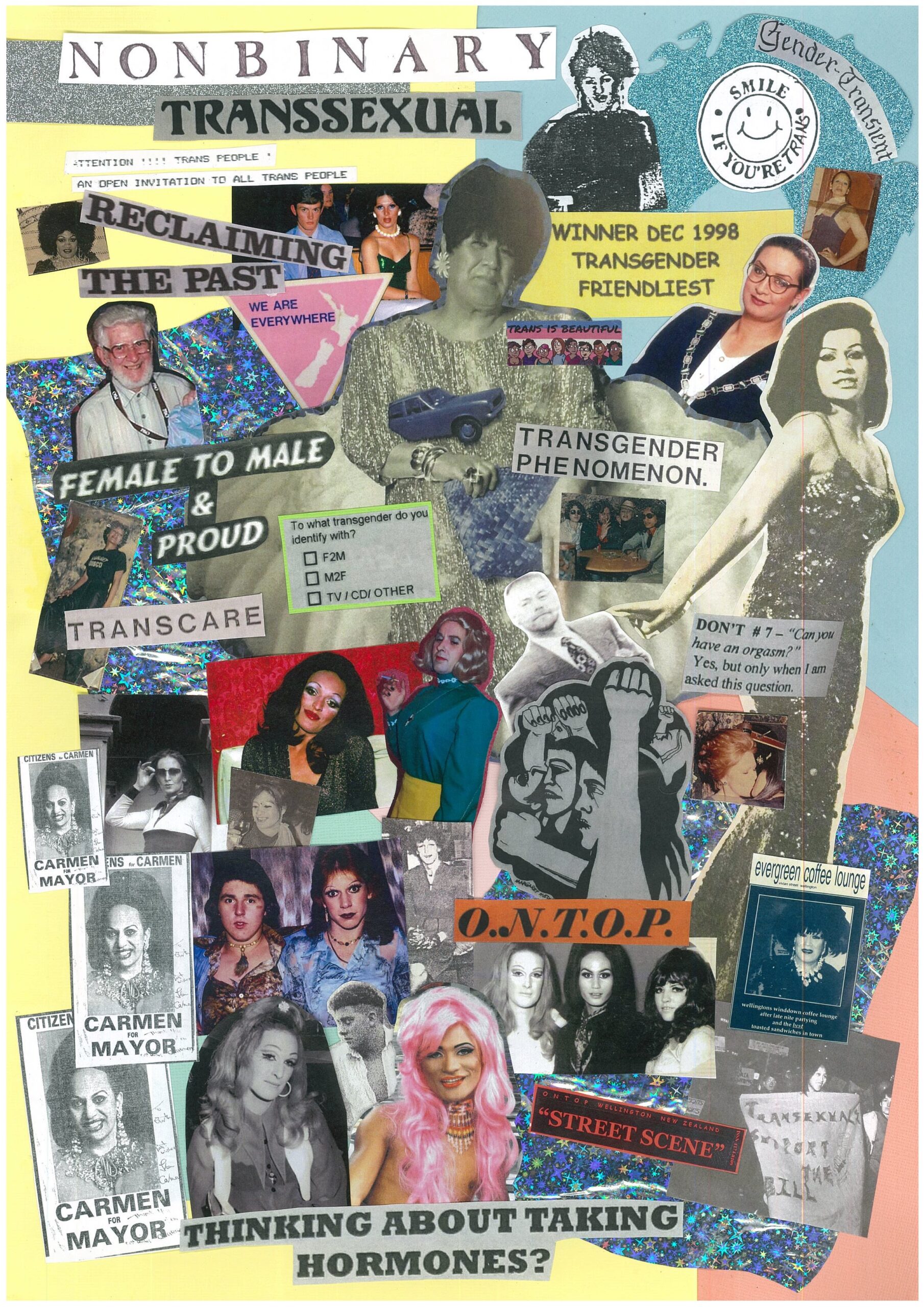

Featured image created by Will Hansen, of composite images belonging to Te Pūranga Takatāpui o Aotearoa | the Lesbian and Gay Archives of New Zealand.